RON HENGGELER |

May 22, 2015

Historic Sacramento

Recently, Dave and I drove to Sacramento and spent the day playing tourists and curious history buffs. We visited the historic Old Town Sacramento Historic District, a unique 28-acre National Historic Landmark District and State Historic Park located along the beautiful Sacramento River. We also visited the Sacramento History Museum, and California's State Capitol Building. Late in the day we drove through the quiet lanes inside the peaceful Sacramento Historic City Cemetery. The grounds keeper Chris was kind enough to allow us in, even though it was past the closing hour. We ended our day by walking across the gold-painted Tower Bridge as the sun was setting. Here are some of my photos from the day.

A view alongside Firehouse Alley to I Street in the Old Town Sacramento Historic District. With California now in its fourth year of drought, brown is the new green. Without the serious drought conditions, this park in Old Town would normally be a lush carpet of green grass. |

The backside of a Gold Rush era building on Firehouse Alley near I Street in Old Town Sacramento Historic District Sacramento, Spanish for "Holy Sacrament," was originally the name of a nearby river that is now called the Feather River; in 1849 the name was taken for the town, which was incorporated in 1850. Sacramento was a rowdy place, full of successful miners who spent their money on gambling and dance halls. In its early days, the town encountered difficulties, with floods in 1849 and 1853 and a fire in 1852. But Sacramento survived to become the capital of California in 1854, paying the state $1 million for the honor. |

The back of a Gold Rush era building on the corner of Firehouse Alley and I Street in Old Town Sacramento Historic District |

A Gold Rush era building on I Street next door to the California State Railroad Museum in Old Town Sacramento Historic District |

The Gold Rush era General Store (still in business) of Collis Huntington and Mark Hopkins, located on I Street in Old Town Sacramento Historic District |

Architectural details of the Gold Rush era buildings on the corner of I Street in Old Town, the Central Pacific Railroad Office and the Sacramento History Museum |

The 19th century Train Depot on Front Street in Old Town Sacramento Historic District |

Architectural details of the Sacramento History Museum |

On Front Street at I Street in Old Town Sacramento Historic District |

The 19th century I Street bridge near the Sacramento History Museum |

PRISONER OF THE RIVER Among the many sailing ships bound for California in 1849 was the LaGrange, a three-masted bark from Salem, Massachusetts. The ship arrived at Sacramento on October 3, 1849, and the following June was purchased by the city for a prison. In preparation for its new role, the ship was stripped to the masts and cells build in its hold. The LaGrange served as Sacramento's jail until November 1859 when it sank during a week-long storm. Other ships were used as hotels and warehouses along the early waterfront before they too bowed to "time and the river". In recent years, nautical archeologists have explored three gold rush vessels and several later boats that are submerged in the Sacramento River. In February 1986 archeologists located what is believed to be the wreckage of the LaGrange, "imprisoned" by riprap and mud just south of the I Street bridge. They found enough evidence---floor frames, hull planks, copper sheathing, curved timbers, and a keelson---to confirm that the vessel was an ocean-going sailing ship of LaGrange's size and age. |

John Sutter, a central figure in California's gold rush and Sacramento's early development, would hardly recognize his embarcadero today. Located just north of the I Street bridge, Sutter's Landing in 1848 was little more than a three-hundred foot sand bar. Following the gold discovery at his Coloma sawmill, hundreds of ocean-going sailing ships crowded Sacramento's waterfront. Too large for river travel, these ships were replaced by smaller one- and two-masted vessels which soon gave way to steam boats. By 1854 the foot of K Street hummed with activity, and the "city of the plain" emerged as the most important shipping terminal in the gold region. In the 1860's, the Central Pacific Railroad constructed an extensive docking facility and freight yard by the river between H and K Streets. In 1910 CP's successor, Southern Pacific, raised its entire waterfront 10 to 15 feet and built a concrete wall along the river from I to R Streets. With the growth of highways, the waterfront declined, and now visitors to Old Sacramento see a partial restoration of the 1860s "scene". |

The 19th century I Street bridge seen from J Street near the waterfront |

Detail of the I Street bridge trestle work A trestle (sometimes tressel) is a rigid frame used as a support, especially referring to a bridge composed of a number of short spans supported by such frames. In the context of trestle bridges, each supporting frame is generally referred to as a bent. Timber and iron trestles were extensively used in the 19th century. |

The underside of the I Street bridge |

Visitors having lunch on the remains of the concrete wall built in 1910. In the 1860's, the Central Pacific Railroad constructed an extensive docking facility and freight yard by the river between H and K Streets. In 1910 CP's successor, Southern Pacific, raised the entire waterfront 10 to 15 feet and built a concrete wall along the river from I to R Streets. |

Tourists peeking inside a building that houses steam locomotives on Front Street |

Front Street near J Street In 1855 construction began on the Sacramento Valley Railroad, with the financial backing of shopkeepers known as the Big Four: Collis P. Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Charles Crocker, and Leland Stanford (after whom Stanford University is named). In 1856 Sacramento became the terminus of California's first railroad. Then came the Pony Express and, in 1861, the transcontinental telegraph. The Central Pacific Railroad joined the east and west coasts in 1869, permitting Sacramento farmers to ship their produce to the east. The railroad also transformed what had been a six-month trip between the coasts to six days; in time it also superseded the river as a means of transportation. In another important change, agriculture eventually replaced the gold mines as the primary industry. |

|

Looking up J Street from Front Street near the Sacramento River |

|

|

Architectural details of the Gold Rush era buildings in Old Town Sacramento |

|

On January 24, 1848, James Wilson Marshall, a carpenter originally from New Jersey found flakes of gold in the American River at the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains near Coloma, California |

Miners extracted more than 750,000 pounds of gold during the California Gold Rush. |

Just days after Marshall’s discovery at Sutter’s Mill, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, ending the Mexican American War and leaving California in the hands of the United States. At the time, the population of the territory consisted of 6,500 Californios (people of Spanish or Mexican decent); 700 foreigners (primarily Americans); and 150,000 Native Americans (barely half the number that had been there when Spanish settlers arrived in 1769). |

Though Marshall and Sutter tried to keep news of the discovery under wraps, word got out, and by mid-March at least one newspaper was reporting that large quantities of gold were being turned up at Sutter’s Mill. Though the initial reaction in San Francisco was disbelief, storekeeper Sam Brannan set off a frenzy when he paraded through town displaying a vial of gold obtained from Sutter’s Creek. By mid-June, some three-quarters of the male population of San Francisco had left town for the gold mines, and the number of miners in the area reached 4,000 by August. |

|

|

As news spread of the fortunes being made in California, the first migrants to arrive were those from lands accessible by boat, such as Oregon, the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii), Mexico Chile, Peru and even China. Only later would the news reach the East Coast, where press reports were initially skeptical. Gold fever kicked off there in earnest, however, after December 1848, when President James K. Polk announced the positive results of a report made by Colonel Richard Mason, California’s military governor, in his inaugural address. As Polk wrote, “The accounts of abundance of gold are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service.” |

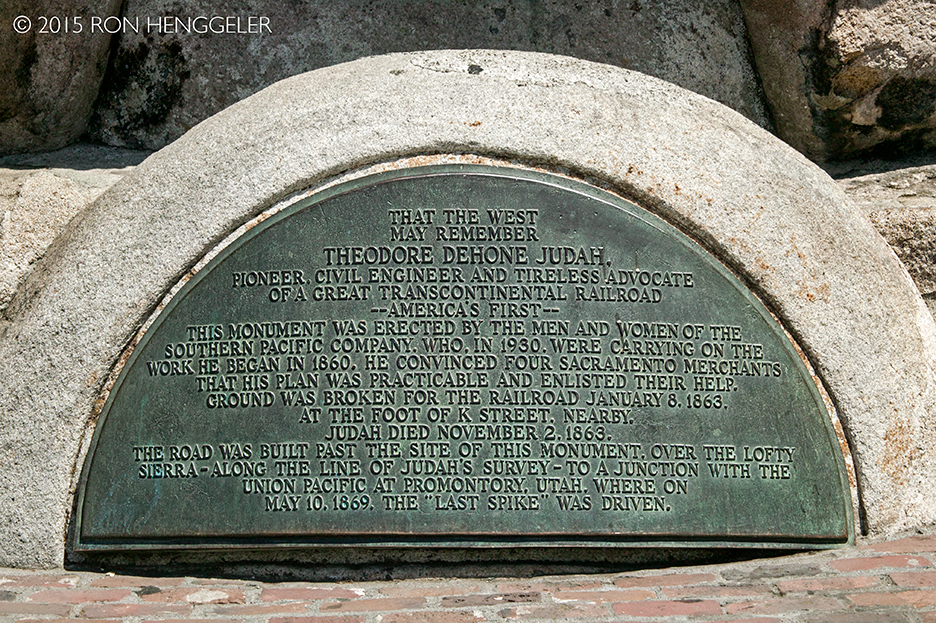

Detail of the Monument to Theodore Judah in Old Town Sacramento Historic District |

As the chief engineer of the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR), Theodore Judah surveyed the route over the Sierra Nevada along which the railroad was to be built during the 1860s. Failing to raise funds for the project in San Francisco, he succeeded in signing up four Sacramento merchants, known as the “Big Four”: Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker. They managed financing and construction of the CPRR. With their backing, Judah lobbied for federal authorization and government financing of the transcontinental railroad inWashington D.C.. He contributed to the passage of the 1862 Pacific Railroad Act which authorized construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad. After passage of the 1862 Act, the Big Four marginalized Judah. They put Crocker in charge of construction. Construction was completed in 1869, with virtually the entire course of the railroad having followed Judah’s plans. |

|

The Sacramento area was originally inhabited by the Nisenan, a branch of the Maidu, who lived in the valley for 10,000 years before white settlers arrived. Spanish soldiers from Mission San Jose, under the command of Lieutenant Gabriel Morago, discovered the Sacramento and American rivers in 1808. The area was not settled until 1839. That year, with the permission of Mexico, Captain John Sutter, a Swiss immigrant who had fled his homeland to escape debtor's prison, built a settlement on 76 acres and called it New Helvetia, after his homeland. He built a fort called Sutter's Fort (which has been restored and can still be seen today). Sutter also constructed a landing on the Sacramento River that he called the Embarcadero and contacted a millwright, James Marshall, to help build the settlement. It was Marshall who in 1848 discovered a gold nugget, thus precipitating the great California Gold Rush of 1849. Sutter's Embarcadero became the gateway to the mines, but Sutter was financially ruined by the influx of newcomers from all over the world who trampled his settlement; even his employees left him to make their fortune. |

Interior view of the Firehouse Restaurant on 2nd Street in Old Town |

|

|

|

|

Architectural details of the rear door to the Sacramento History Museum |

A school's classroom field trip to the Sacramento History Museum Shown here are the kids panning for gold outside in front of the museum |

Sacramento History Museum Gold, Greed, & Speculation: The Beginnings of Sacramento City – The museum’s lobby gallery presents the first fifty years of Sacramento City. Through historic artifacts and an interactive image collage mural, the drama of Sacramento’s beginnings unfolds. Visitors get acquainted with Sacramento’s rise during the California Gold Rush, the struggles early citizens faced in creating this new city, and the economic pursuits that shaped our city’s destiny. |

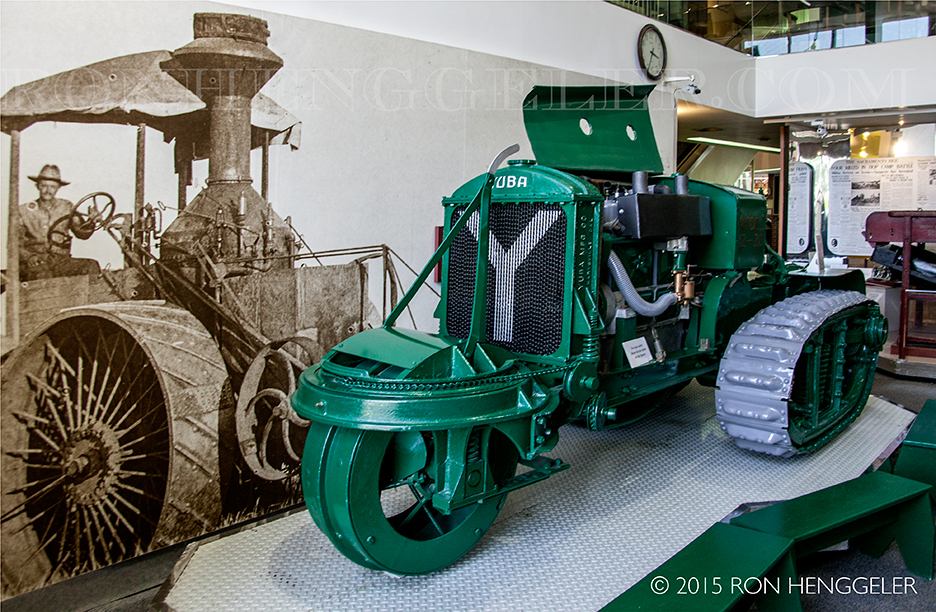

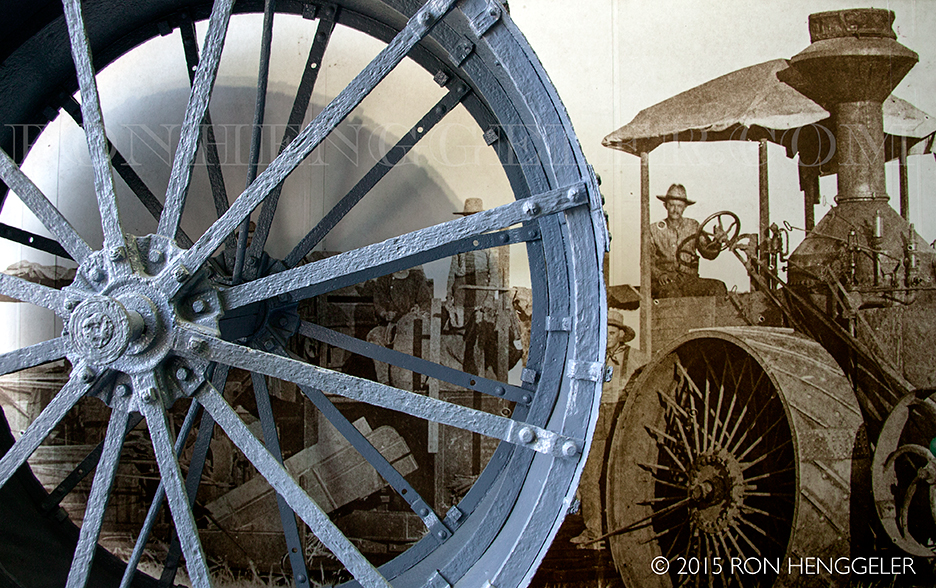

A display at the Sacramento History Museum |

A display at the Sacramento History Museum |

A display at the Sacramento History Museum |

A display at the Sacramento History Museum |

A display at the Sacramento History Museum |

Painted in 1853, this watercolor by Henry Walton portrays miner William D. Peck weighing gold in his cabin in the town of Rough and ready, California. Sacramento History Museum The discovery of gold nuggets in the Sacramento Valley in early 1848 sparked the Gold Rush, arguably one of the most significant events to shape American history during the first half of the 19th century. As news spread of the discovery, thousands of prospective gold miners traveled by sea or over land to San Francisco and the surrounding area; by the end of 1849, the non-native population of the California territory was some 100,000 (compared with the pre-1848 figure of less than 1,000). A total of $2 billion worth of precious metal was extracted from the area during the Gold Rush, which peaked in 1852. |

California News (1850) By artist, William Sydney Mount Sacramento History Museum |

Mining on the American River, Near Sacramento (c.1852) By photographer, George H. Johnson Sacramento History Museum Throughout 1849, people around the United States (mostly men) borrowed money, mortgaged their property or spent their life savings to make the arduous journey to California. In pursuit of the kind of wealth they had never dreamed of, they left their families and hometowns; in turn, women left behind took on new responsibilities such as running farms or businesses and caring for their children alone. Thousands of would-be gold miners, known as ’49ers, traveled overland across the mountains or by sea, sailing to Panama or even around Cape Horn, the southernmost point of South America. |

Miner with Pick and Shovel (c.1852) Unknown maker Reproduction from the original daguerreotype; Courtesy of the Oakland Museum of California The discovery of gold nuggets in the Sacramento Valley in early 1848 sparked the Gold Rush, arguably one of the most significant events to shape American history during the first half of the 19th century. As news spread of the discovery, thousands of prospective gold miners traveled by sea or over land to San Francisco and the surrounding area; by the end of 1849, the non-native population of the California territory was some 100,000 (compared with the pre-1848 figure of less than 1,000). A total of $2 billion worth of precious metal was extracted from the area during the Gold Rush, which peaked in 1852. |

Sacramento History Museum |

Crossing the Plains (1856) By artist, Charles Christian Nahl Sacramento History Museum |

After 1850, the surface gold in California largely disappeared, even as miners continued to arrive. Mining had always been difficult and dangerous labor, and striking it rich required good luck as much as skill and hard work. Moreover, the average daily take for an independent miner working with his pick and shovel had by then sharply decreased from what it had been in 1848. As gold became more and more difficult to reach, the growing industrialization of mining drove more and more miners from independence into wage labor. The new technique of hydraulic mining, developed in 1853, brought enormous profits but destroyed much of the region’s landscape. |

Sacramento History Museum |

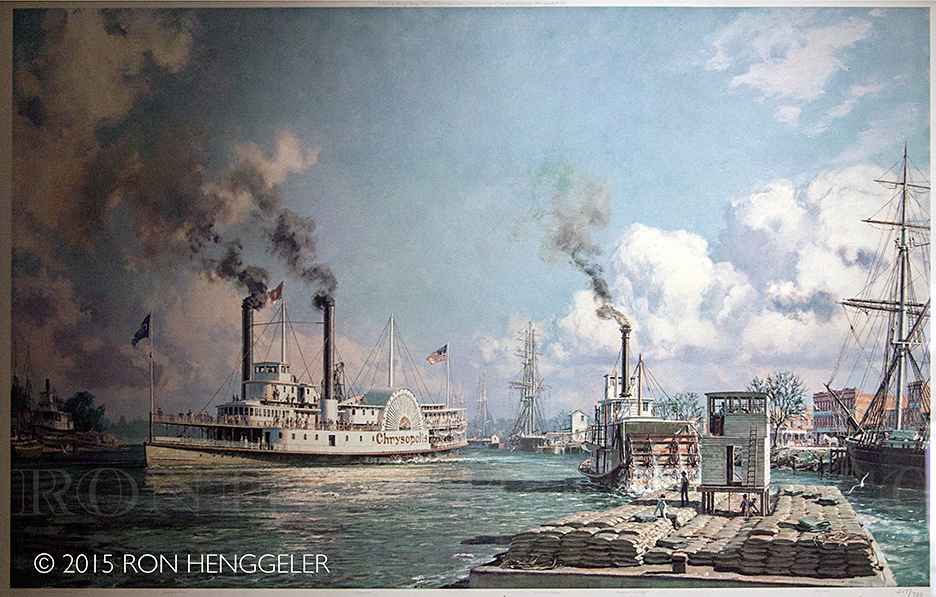

HAZARDS OF RIVER TRAVEL It was not always smooth sailing for the passengers of paddle wheelers. The dangers included being sunk by snagging, collusion, being rammed and, the most feared of all, explosion. Blowing up could be caused by faulty boilers or by careless engineers who let the steam pressure build too high. The least forgivable cause of boiler pressure was racing, which lured boat owners to demand more speed than was wise. Hundreds of man women and children lost their lives because of their attempts to set speed records. Steam pressure will build and then KABOOM!---everything went sky high. |

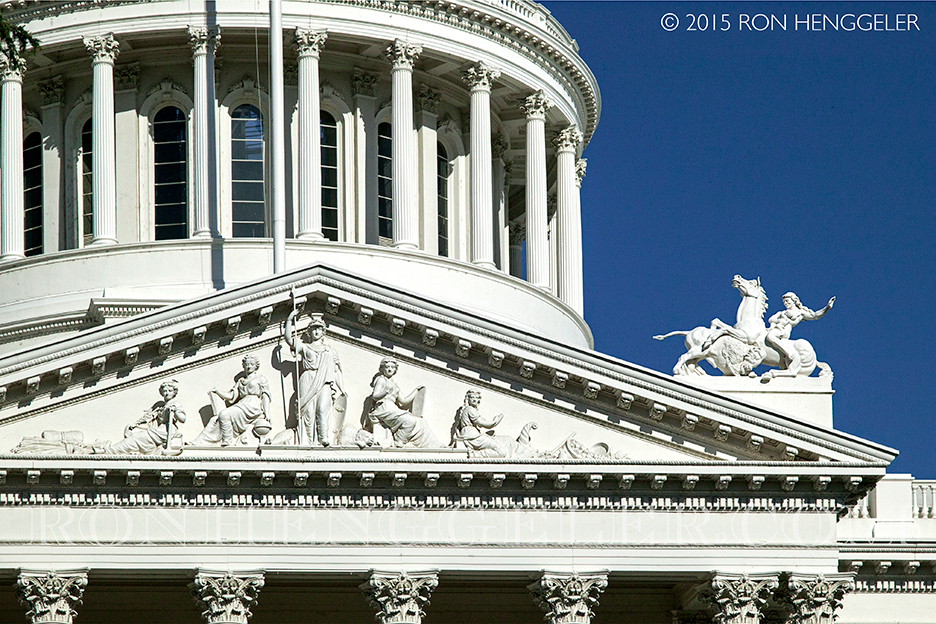

The California State Capitol Building seen from 10th Street in Sacramento |

Close up of the California State Capitol's entrance |

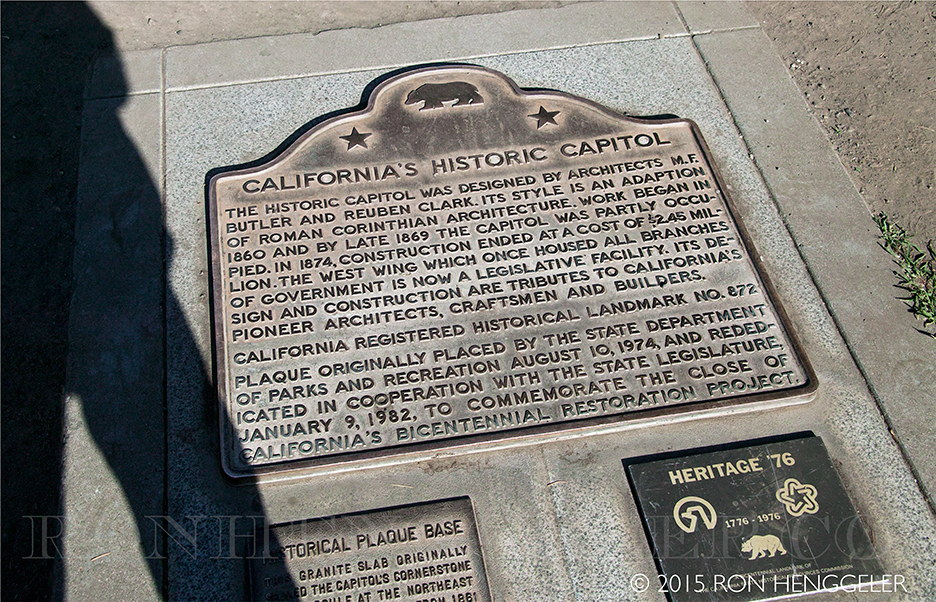

The building is based on the U.S. Capitol building in Washington D.C. The west facade ends in projecting bays, and a portico projects from the center of the building. At the base of the portico, seven granite archways brace and support the porch above. Eight fluted Corinthian columns line the portico. A cornice supports the pediment above depicting Minerva surrounded by Education, Justice, Industry, and Mining. |

Designed in the neoclassical style, the Capitol reflects the Greek and Roman influences of our democracy. |

|

|

Visitors’ first glimpse of the Rotunda is usually from the first floor. Standing on flooring of Belgium black and Vermont white marble tiles arranged in a checkerboard pattern, visitors are surrounded by decorative murals. These murals featuring design motifs of swirling foliage, urns and stylized griffins, a mythical animal with the head of a lion and a body of an eagle, artists first painted these murals on canvas, after which, workers permanently attached them to the plaster walls. Separating these murals are four barreled niches featuring faux marbleized paint. Inside the niches are urns, which, on occasion, hold fresh-cut flower arrangements. The focus of this room, however, is a massive statue made of Carrara marble. Slightly over life size, the statue, titled Columbus' Last Appeal to Queen Isabella, has rested in the center of the Rotunda since 1883. Although visitors can see portions of the inner dome from the first floor, the best view can be seen from the second floor. |

Statue of Queen Isabella and Columbus commemorating her decision to finance a voyage to the New World By American-born sculptor Larkin Goldsmith Mead |

The interior dome of the Capitol combines Victorian detail with Classical Renaissance elements and governmental symbols. From the second floor visitors have an unobstructed view of the interior ornamentation of inner dome. Here visitors’ cannot help but find their eyes drawn upward in wonderment. The Rotunda rises nearly 100 feet from a circular walk on the second floor to the oculus, a large window located at the apex of the dome. Sixteen windows, each surrounded by eighteen light bulbs, shed light on the great domed space. The ornamentation of the dome includes bands of cast iron, plaster, and painted canvas. Like the rest of the building, the Rotunda ornamentation features design motifs common to neoclassic architecture, including columns with Corinthian capitals, egg and dart moldings, and festoons featuring cornucopias and fruit. |

|

|

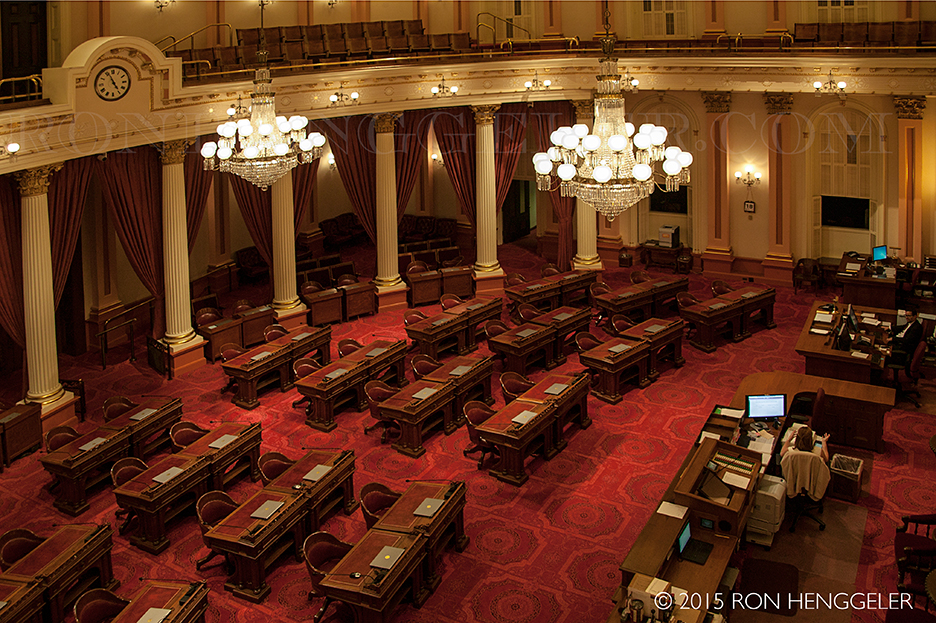

The California Senate chamber seats its forty members in a large chamber room decorated in red, which is a reference to the British House of Lords also the upper house of a bicameral legislature. The chamber is entered through a second floor corridor. From the coffered ceiling hangs an electric reproduction of the original gas chandelier. A hand-carved dais caps off a recessed bay framed by Corinthian columns. |

|

While a rotunda is a feature of nearly every state capitol in the United States, the California State Capitol Rotunda is by no means generic. In fact, perhaps the most impressive decorations in the Rotunda are those related the California’s State symbols. A band of cast iron grizzly bears look down on visitors and stylized versions of Minerva, the Roman goddess who is featured of the Great Seal of California, set atop the arched openings that lead into the second floor rotunda walkway. Such California specific ornamentation exists throughout the rest of the building. What visitors cannot see is the fact that directly above the Oculus is a circular metal staircase that extends another 90 feet to the Cupola, a small open space located on top of the Capitol’s outer dome. The frescoing of the interior dome reflects the Renaissance Revival style popular during Victorian times. |

A view of the far distant Tower Bridge from the California Capitol Building |

|

|

|

|

Statue of Queen Isabella and Columbus commemorating her decision to finance a voyage to the New World The statue, “Columbus’ Last Appeal to Queen Isabella,” commemorates the Spanish monarch’s underwriting of Columbus’ voyage to the New World. The person who commissioned American-born sculptor Larkin Goldsmith Mead to make the statue died before its delivery. But the man’s neighbor, Darius Ogden Mills, a wealthy Northern California banker, bought the statue and donated it to California, and the statue was put in the rotunda in 1883. Isabella and Columbus were relocated to the nearby Library and Courts building in 1975 as workers began restoring the Capitol. The statue initially was missing from the reopened rotunda in 1982, but lobbying by Italian Americans returned it to the rotunda the following year, Sgromo said. “It’s become a major historical treasure for the Capitol,” runner-up in significance to the portrait of George Washington in the Senate chambers. Meanwhile, the practice of tossing coins at Isabella’s crown on the last night of the legislative session started sometime in the 1940s |

Statue of Queen Isabella and Columbus commemorating her decision to finance a voyage to the New World By American-born sculptor Larkin Goldsmith Mead |

Entrance to the California Governor's Office |

|

The first domes in architectural history were originally built for temples or churches. At first they were squat and low, appearing insignificant from the outside, yet celestial from the interior. Early architects did not have the means to construct a dome that would have the same grand appearance from both inside and outside the building until 1418 when an Italian architect named Filippo Brunelleschi conceived the idea of employing mathematical perspective to establish new rules of proportion and symmetry. Brunelleschi's theory of perspective was developed from the fact that the apparent size of an object decreases with the increasing distance from the eye. This knowledge was used by Brunelleschi in the successful construction of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, Italy. His innovative plans included an inner hemispherical dome-within-a-dome. A second brick dome was to be placed on top and nine sandstone rings would then hold the structure together like a barrel. This was the first time that a dome created the same strong visual effect on the exterior as it did on the interior. Brunelleschi's method of design and construction was employed in building California's State Capitol dome. The interior of the dome employs iron frame construction, allowing the majestic copper outer dome to rise above Capitol Park and the Sacramento skyline. From inside the building, the beauty of the Victorian detailing on the inner dome is visible in all its majesty. |

|

Pietro Mezzara, California's first major sculptor, created the statuary for the Capitol's rooftop and the pediment. Thirty figures, urns, and emblems adorned the Capitol in 1873. |

|

|

Symbols Unique to the Capitol's Architecture According to ancient Roman myth, the goddess Minerva was born fully grown. Just as Minerva was born fully grown, so California became a state without first having been a territory. Minerva's image on the Great Seal symbolizes California's direct rise to statehood. California's Great Seal The Great Seal is one of many symbols that decorate the Capitol and represent the state's people and resources. Delegates at California's first constitutional convention determined its design, but not without controversy. Records of their lively debate document the delegates' disputes. Their conversations show that symbols take on different meanings to different people. When presented with the proposed design, one delegate rejected it. He felt bags of gold and bales of merchandise should replace the prospector and the bear. Senator Mariano Vallejo took another point of view: He believed that a bear should appear only if shown being captured by a lasso-wielding cowboy. In the end, the delegates overcame their differences. They officially adopted the seal on October 2, 1849. In 1907 a stained glass representation of the Great Seal was installed in the ceiling of the hallway leading from the Capitol's rotunda. To show off an exciting technological advance of the time, electricity rather than sunshine was used to light up the seal. Today the Great Seal is stamped on all approved bills signed into law, as well as other important government documents. In fact a faint image of the seal appears on every California driver's license |

The California State Capitol was in part modeled after the United States Capitol, which features a bronze statue of “Freedom” as its crowning ornament. Given the already marked resemblance between the two Capitols’ architecture, the absence of a statue on the California State Capitol was intended to distinguish the two buildings. In addition, the presence of a gold ball, reminiscent of a gold nugget, reminds visitors to the Capitol of California’s Gold Rush heritage. On October 29, 1871, the crowning ornament, a gold-plated copper ball, was affixed to the cupola at the apex of the Capitol. This ball, nearly three feet in diameter, was part of Rueben Clark’s original plans. Interesting Fact: Gilding the Cupola In July 1880 the Capitol building received a another spectacular embellishment-the gilding of the cupola roof directly below the ball. This sparkling gold enhancement made the Capitol an even more attractive focal point from around the city. |

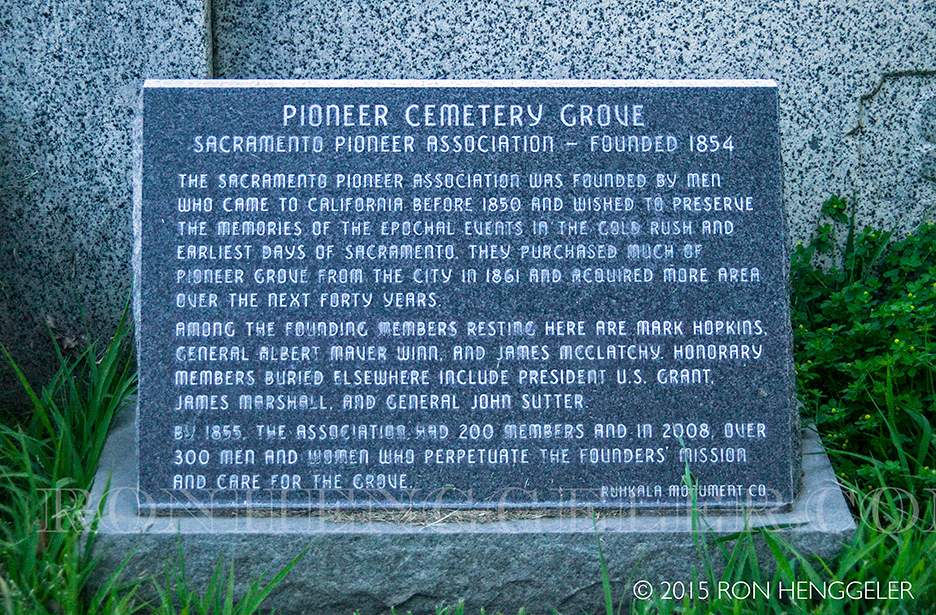

The Sacramento Historic City Cemetery (or Old City Cemetery), located at 1000 Broadway, at 10th Street, is the oldest existing cemetery in Sacramento CaliforniaThe cemetery is located at the highest point in Sacramento. It was designed to resemble a Victorian garden and sections that are not located in level areas are surrounded by brick or concrete retaining walls to create level terraces.The cemetery grounds are noted for their roses which are said to be among the finest in California. |

Mark Hopkins Monument Construction began on this splendid mausoleum in 1878 when the then very wealthy Mary Hopkins wished to provide a suitable resting place for her recently deceased husband Mark Hopkins. Mark Hopkins had operated first a grocery store and then a hardware store in Sacramento in the 1850s and became a founding partner of the Central Pacific Railroad, a visionary undertaking to build the first crossing of the continent by rail. One of the legendary Big Four, he served as Treasurer of the Central Pacific Railroad throughout its expansion until his death at sixty-five. A full year and a half was required to erect the mausoleum, with workmen constructing around the clock to finish it. A special spur rail line was laid to transport the tons of granite from the depot to the cemetery and along a cemetery pathway to the building site. A framework was erected with the moving hoist. The contractor was Griffith Company of Penryn, California, who traveled to the Rocky Mountains to mine the red granite. The Rhukala Co. of Sacramento later took over the project. There are over 350 tons of Rocky Mountain Red Granite and many tons of gray granite from a quarry near Donner Lake, the highest point of the Central Pacific Railroad's construction in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The red stone came from a quarry near the highest point of the Union Pacific Railroad's crossing of the Rocky Mountains. It was selected by Mrs. Hopkins because Mr. Hopkins had admired it on his first trip east on the transcontinental railroad. The walkway around the vault is comprised of three kinds of granite - red, gray and Penryn Black. The interior is said to be of polished white Italian marble. All together, there are probably well in excess of 900,000 pounds of stone in the structure, and there is a base of over six feet of solid concrete. The tomb was built to accommodate sixteen caskets, there being eight marble grottos on either end of the building; however, there are only four internments recorded, and one of those is in question. Mark Hopkins and his brother Moses are on the west side, and his brother Ezra and nephew Samuel on the east. Samuel died at seas on the way home from the Orient. Those who die at sea are usually buried at sea, but his name is carved into the door on the southeast side of the vault. |

The final resting place of Mark Hopkins Mark Hopkins (September 1, 1813 – March 29, 1878) was one of four principal investors who formed the Central Pacific Railroad along with Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, and Charles Crocker in 1861. A bronze plaque near this sarchophas reads: MARK HOPKINS THIS PLAQUE IS DEDICATED IN HONOR OF |

Final resting place of Mark Hopkins in the Sacramento Historic City Cemetery (or Old City Cemetery), located at 1000 Broadway, at 10th Street In 1861, as part of the Big Four, he founded the Central Pacific Railroad. Sometimes called "Uncle Mark", he was the eldest of the four partners and was well known for his thriftiness (it was said that he knew how to "squeeze 106 cents out of every dollar",a reputation that gained him the post of company treasurer. Noted American historian Hubert Howe Bancroft quotes Collis Huntington as saying, "I never thought anything finished until Hopkins looked at it". Bancroft described Hopkins as the "balance-wheel of the Associates and one of the truest and best men that ever lived. |

The cemetery was established in 1849 when Sacramento founder John Sutter Jr.donated 10 acres to the city for this purpose.The grounds were landscaped in the Victorian Garden style popular at the time. In 1850, 600 victims of the Cholera epidemic that swept the city were buried in mass graves in City Cemetery. The remainder of the 800 to 1000 victims claimed by the epidemic were buried in the nearby New Helvetia Cemetery, also in mass graves. Because the New Helvetia Cemetery was prone to flooding, these graves were later transferred to City Cemetery. In 1852, a monument was erected to those who died however the exact location of either burial plot is not known. |

|

|

|

|

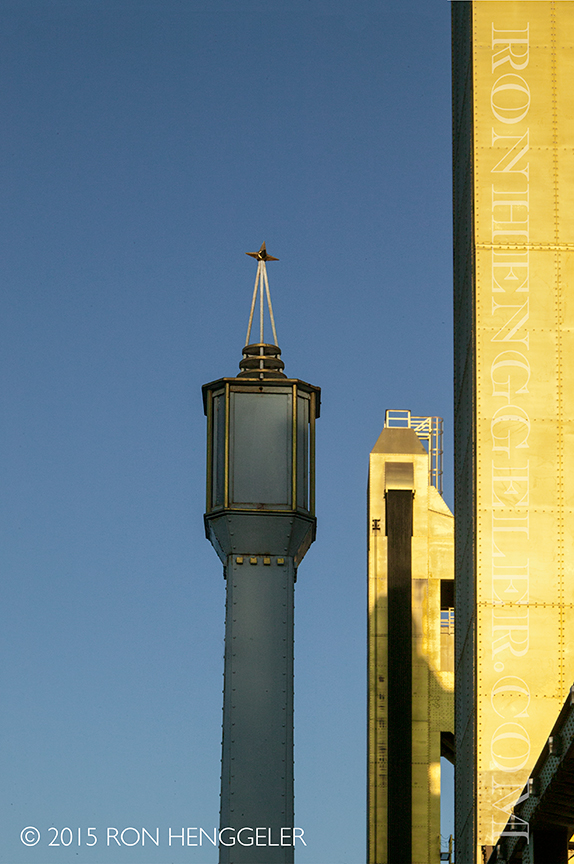

The Tower Bridge is a vertical lift bridge across the Sacramento River, linking West Sacramento in Yolo County to the west, with the capital of California, Sacramento, in Sacramento County to the east. |

For years, the bridge was painted silver, but people complained about glare off the bridge. In June 1976 it was painted a yellow-ochre color, to be representative of the gold leafed cupola on the nearby State Capitol. In 2001, as the old paint job could hardly be distinguished, residents who lived within 35 miles of the capital voted on a new color scheme. Their choices were burgundy, green, silver and gold; or all gold. The winning color was all gold, and it was repainted in 2002. However, that did not lessen the bridge's color controversy. Some people complained that the new paint was not as gilded as advertised. Others have suggested that copper would have been a far better color choice, especially in the context of nearby buildings. The new coat is expected to last 30 years. |

Detail of the Tower Bridge in Sacramento |

Detail of the Tower Bridge in Sacramento |

Detail of the Tower Bridge in Sacramento |

|

|

Detail of the Tower Bridge in Sacramento |

Detail of the Tower Bridge in Sacramento |

|

|

Detail of the Tower Bridge in Sacramento |

Detail of the Tower Bridge in Sacramento |

Newsletters Index: 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006

Photography Index | Graphics Index | History Index

Home | Gallery | About Me | Links | Contact

© 2015 All rights reserved

The images are not in the public domain. They are the sole property of the

artist and may not be reproduced on the Internet, sold, altered, enhanced,

modified by artificial, digital or computer imaging or in any other form

without the express written permission of the artist. Non-watermarked copies of photographs on this site can be purchased by contacting Ron.