RON HENGGELER |

June 11, 2015

The ethereal fog at Point Reyes National Seashore

Earlier this week, Dave and I took a day-long road trip north of San Francisco to the beautiful Point Reyes National Seashore. On the way there, we detoured off the normal route on Sir Francis Drake Blvd. and drove through miles of dry farmland to visit the hamlet-like town of Nicasio, and to try and see the George Lucas Skywalker Ranch. Here are some of my photos from the day.

The distant San Francisco skyline and the early morning fog as seen from the Wolfpack Ridge Rd. along the Redwood Highway N101. |

St. Mary's Church in Nicasio. Built in 1867, the church was constructed from locally milled redwood at a cost of $3,000 – money that was raised by the townspeople. |

Near Nicasio, the dry California landscape after four years of drought. |

A building on the Point Reyes Petaluma Rd near the town of Point Reyes Station. |

Detail of the mural on the building |

The Pastoral Lands and Drakes Estero, as seen while driving along Sir Francis Drake Blvd in the Point Reyes National Seashore. When one crosses Inverness Ridge toward the Point Reyes headlands, one leaves the pine/fir forest behind and enters the stark beauty of the coastal grasslands, dotted with cattle and scattered ranches. |

The Pastoral Lands and a fog-shrouded Point Reyes Beach North, as seen while driving along Sir Francis Drake Blvd in the Point Reyes National Seashore. This open, working landscape is known as the Pastoral Zone. At first glance, open pastures and rolling fencelines are punctuated by windbreaks, stockponds, and feedlots arrayed around a ranch core. There, the mix of nineteenth century redwood homes and barns with twentieth century aluminum and steel utility buildings becomes evident, suggesting the evolution of the dairy industry. In fact, the National Seashore visitor has happened upon one of the earliest and largest examples of industrial-scale dairying in the state of California. |

The Pastoral Lands, and the marinelayer coming off the Pacific, viewed while driving along Sir Francis Drake Blvd in the Point Reyes National Seashore. The 1849 California Gold Rush brought an influx of capitalists, merchants, professional practitioners, laborers, and agriculturists, amongst others seeking alternative wealth along the shores of San Francisco Bay. Some of those who vainly sought mineral gold in the Sierra Nevada foothills came further west, finding gold of another kind at Point Reyes. With their dairying skills honed in their previous homes, they could envision production of golden wheels of cheese and casks of butter to provision the growing population of nearby San Francisco. The treeless coastal plain beckoned with opportunity. |

View along along Sir Francis Drake Blvd of the distant Chimney Rock in the Point Reyes National Seashore The Franciscan missionaries set the stage for the explosion of dairy in west Marin with the introduction of feral cattle in 1817. They established the San Rafael Asistencia, near San Francisco Bay, as an annex to Mission Dolores in San Francisco, serving as a recuperative center for ailing Coast Miwok and Ohlone natives. Secularization of the missions following Mexican independence from Spain led to land grant subdivision and the expansion of cattle ranching on the peninsula. |

The Pastoral Lands in the Point Reyes National Seashore The advancing front of Americano ranchers brought to light poor record keeping, and the behavior of several Mexicano land grantees coveting and utilizing a neighbor’s adjacent parcel. As land was sold to the new immigrants, the title to the land usually became ensnared in litigation. During a five-year period ending in 1857, the San Francisco law firm of Shafter, Shafter, Park, and Heydenfeldt obtained title to over 50,000 acres on the peninsula, encompassing the coastal plain and most of Inverness Ridge. Unlike the small dairy operations pre-existing on the peninsula, these Vermont-native lawyer / businessmen saw the opportunity to market large quantities of superior quality butter and some cheese under a Point Reyes brand to San Francisco. The remote location of Point Reyes would be overcome with the expeditious delivery of finished products and livestock to the foot of Market Street by way of small schooners, and eventually by rail and ferry. |

A view along Sir Francis Drake Blvd through the Pastoral Lands in the Point Reyes National Seashore |

Imagine what this windswept, fog-enshrouded landscape may have looked like almost two hundred years ago, before the first cattle made their way here. Imagine Coast Miwok coexisting with tule elk, grizzly bear, mountain lion, whales, dolphins, countless birds and their innumerable prey species. |

Marinelayer of fog on the road leading from the parking lot to the historic Point Reyes Lighthouse. We began our day at Point Reyes with a visit to the historic lighthouse. The average wind speeds the evening before had been clocked at 40 miles per hour near the Point Reyes Lighthouse, with a peak wind speed of 75 miles per hour. |

When we arrived at around 2pm, the area was shrouded in a marinelayer of fog. As you'll see by the photos that follow, the rest of our day was spent being in the fog, below the fog, or above it. |

Like a ghostly phantom . . . a fast-passing crow appears and disappears in the fog . . . glimpsed while walking on the road to the historic Point Reyes Lighthouse |

|

. . . a fast-passing crow appears and disappears in the fog . . . like a ghostly phantom |

|

|

|

|

|

Warm air masses moving landward over the cold water create dense fog from April through October. Often while this headland is cloaked in fog, the weather only 13 miles inland at Olema is sunny. |

|

|

|

|

At the top of the coastal ridge looking down on the Point Reyes Lighthouse is a sign that reads: You are standing on what may be the windiest point on America's Pacific Coast. The headland's steep profile channels and amplifies unimpeded ocean winds. 40 mph winds are common here, and gusts exceeding 100 mph have been recorded. Park rangers close the lighthouse stairs when winds become dangerously strong. |

Warm air masses moving landward over the cold water create dense fog from April through October. Often while this headland is cloaked in fog, the weather only 13 miles inland at Olema is sunny. |

This furry alga (Trentepehlia) grows at Point Reyes on the shadier north face of rocks. Although it contains green chlorophyll, red pigments predominate. Algae such as these, called "rock violets", need no soil. |

Point Reyes is the windiest place on the Pacific Coast and the second foggiest place on the North American continent. Weeks of fog, especially during the summer months, frequently reduce visibility to hundreds of feet. The Point Reyes Headlands, which jut 10 miles out to sea, pose a threat to each ship entering or leaving San Francisco Bay. The historic Point Reyes Lighthouse warned mariners of danger for more than a hundred years. |

The Point Reyes Lighthouse, built in 1870, was retired from service in 1975 when the U.S. Coast Guard installed an automated light. They then transferred ownership of the lighthouse to the National Park Service, which has taken on the job of preserving this fine specimen of our heritage. |

|

The Point Reyes Light First Shone in 1870. The Point Reyes Lighthouse lens and mechanism were constructed in France in 1867. The clockwork mechanism, glass prisms and housing for the lighthouse were shipped on a steamer around the tip of South America to San Francisco. The parts from France and the parts for the cast iron tower were transferred to a second ship, which then sailed to a landing on Drakes Bay. The parts were loaded onto ox-drawn carts and hauled three miles over the headlands to near the tip of Point Reyes, 600 feet above sea level. |

Meanwhile, 300 feet below the top of the cliff, an area had been blasted with dynamite to clear a level spot for the lighthouse. To be effective, the lighthouse had to be situated below the characteristic high fog. It took six weeks to lower the materials from the top of the cliff to the lighthouse platform and construct the lighthouse. Finally, after many years of tedious political pressure, transport of materials and difficult construction, the Point Reyes Light first shone on December 1, 1870. |

|

Lighthouses provide mariners some safety by warning them of rocky shores and reefs. They also help mariners navigate by indicating their location as ships travel along the coast. Mariners recognize lighthouses by their unique flash pattern. On days when it is too foggy to see the lighthouse, a fog signal is essential. Fog signals sound an identifying pattern to signal the location to the passing ships. Unfortunately, the combination of lighthouses and fog signals does not eliminate the tragedy of shipwrecks. |

Because of this ongoing problem, a lifesaving station was established on the Great Beach north of the lighthouse in 1890. Men walked the beaches in four-hour shifts, watching for shipwrecks and the people who would need rescue from frigid waters and powerful currents. A new lifesaving station was opened in 1927 on Drakes Bay near Chimney Rock and was active until 1968. Today, it is a National Historic Landmark and can be viewed from the Chimney Rock Trail. |

The Lighthouse is an Enduring Historical Legacy The historic Point Reyes Lighthouse served mariners for 105 years before it was replaced. It endured many hardships, including the April 18, 1906, earthquake, during which the Point Reyes Peninsula and the lighthouse moved north 18 feet in less than one minute! The only damage to the lighthouse was that the lens slipped off its tracks. The lighthouse keepers quickly effected repairs and by the evening of the eighteenth, the lighthouse was once again in working order. The earthquake occurred at 5:12 am and the lighthouse was scheduled to be shut down for regular daytime maintenance at 5:25 am Although the earthquake caused much devastation and disruption elsewhere, the Point Reyes Lighthouse was essentially only off-line for thirteen minutes! |

|

|

|

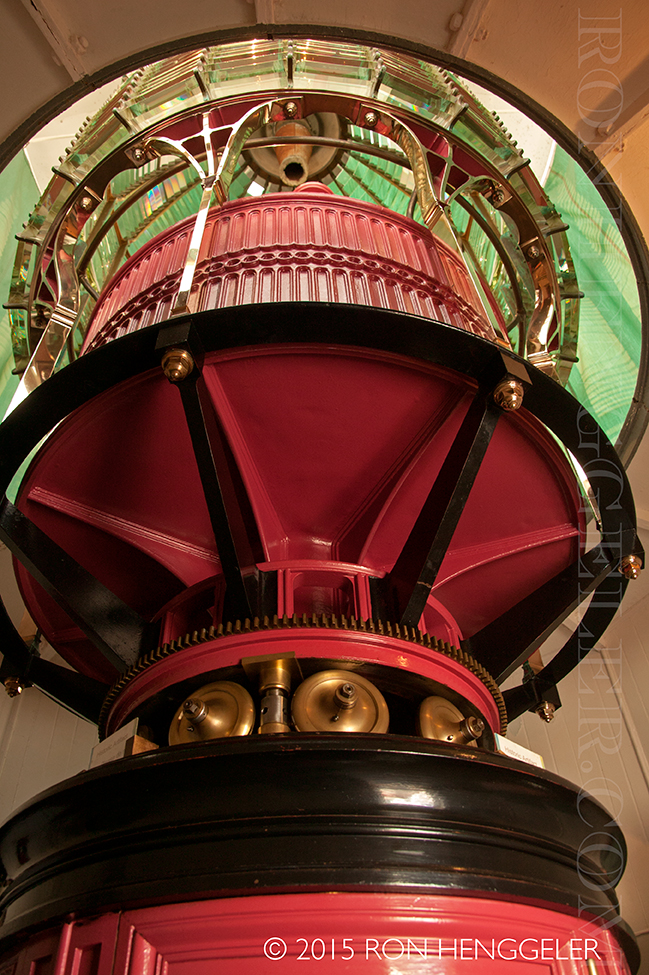

The Fresnel Lens: The French JewelsThe lens in the Point Reyes Lighthouse is a "first order" Fresnel (fray-nel) lens, the largest size of Fresnel lens. Augustin Jean Fresnel of France revolutionized optics theories with his new lens design in 1823. |

Before Fresnel developed this lens, lighthouses used mirrors to reflect light out to sea. The most effective lighthouses could only be seen eight to twelve miles away. After his invention, the brightest lighthouses could be seen all the way to the horizon, about twenty-four miles. |

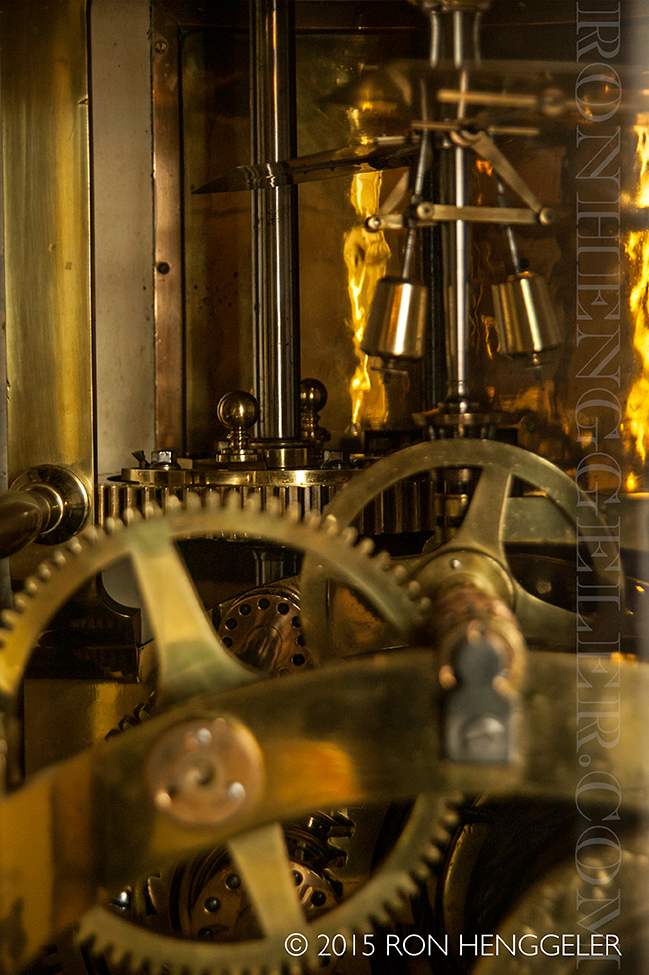

Every evening, a half-hour before sunset, a keeper walked down the wooden stairs to light the oil lamp, the lighthouse's source of illumination. Once the lamp was lit, the keeper wound the clockwork mechanism, lifting a 170 pound weight, which was attached to the clockwork mechanism by a hemp rope, nine feet off the floor. The earth's gravity would then pull the weight, through a small trap door, to the ground level 17 feet below. The clockwork mechanism was built to provide resistance so that it would take two hours and twenty minutes for the weight to descend the 17 feet. And as the weight descended and the clockwork mechanism's gears spun, the Fresnel lens would turn so that the light appeared to flash every five seconds. In addition to winding the clockwork mechanism every two-hours and twenty minutes throughout the night, the keeper had to keep the lamp wicks trimmed so that the light would burn steadily and efficiently, thus the nickname "wickie." |

The Fresnel lens intensifies the light by bending (or refracting) and magnifying the source light through crystal prisms into concentrated beams. The Point Reyes lens is divided into twenty-four vertical panels, which direct the light into twenty-four individual beams. |

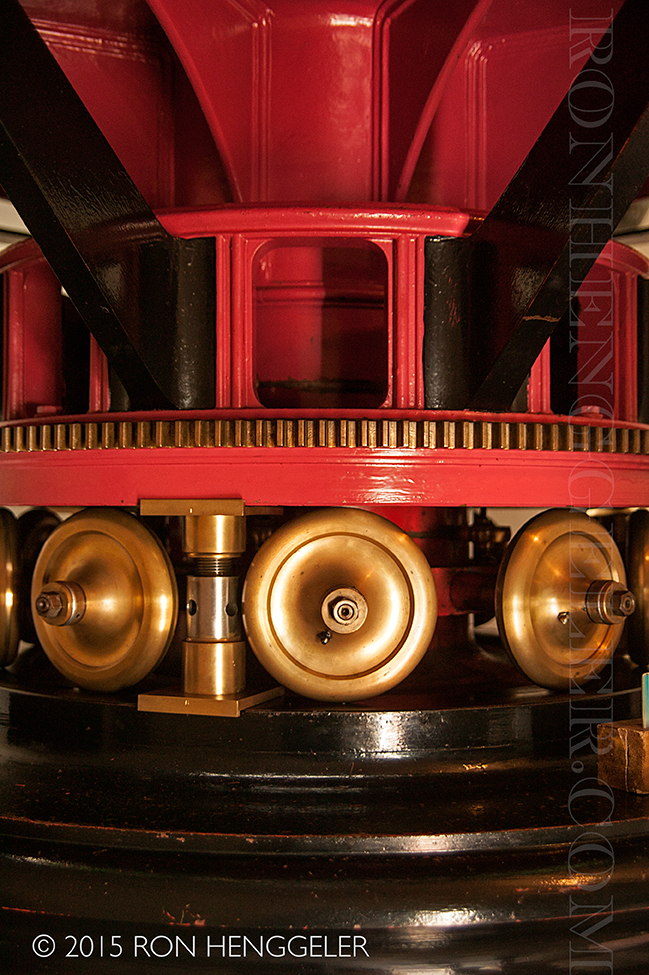

A counterweight and gears similar to those in a grandfather clock rotate the 6000-pound lens at a constant speed, one revolution every two minutes. This rotation makes the beams sweep over the ocean surface like the spokes of a wagon wheel, and creates the Point Reyes signature pattern of one flash every five seconds. |

The National Park Service is now responsible for the maintenance of the lighthouse. Park rangers now clean, polish and grease it, just as lighthouse keepers did in days gone by. With this care, the light can be preserved for future generations--to teach visitors of maritime history and of the people who worked the light, day in and day out, rain or shine, for so many years. |

Keeping the lighthouse in working condition was a twenty-four hour job. The light was lit only between sunset and sunrise, but there was work to do all day long. The head keeper and three assistants shared the load in four six-hour shifts. |

|

|

The Point Reyes Lighthouse, built in 1870, was retired from service in 1975 when the U.S. Coast Guard installed an automated light. They then transferred ownership of the lighthouse to the National Park Service, which has taken on the job of preserving this fine specimen of our heritage. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A water tower shrouded in the fog seen along the trail near the Point Reyes Lighthouse |

|

|

The road to Chimney Rock |

The headland is renowned for spring wildflowers, elephant seal colonies and seasonal whale watching. Clear days afford sweeping views of Drakes Beach, Drakes Estero, Limantour Beach and the Farallon Islands. |

The ancient home of the Coast Miwok people, the dramatic landscape of the Point Reyes peninsula with its wave battered cliffs, remained undiscovered by European explorers until the late 1500's. |

Sir Francis Drake probably first sighted and mapped the fog-shrouded headlands in 1579, at which time he is thought to have camped along the beach which today bears his name. Drake's quest for new lands and riches had taken him around South America to the Spanish trade routes of the Pacific Ocean. His ship, the Golden Hinde, was full of gold and luxuries such as porcelain, taken from Spanish galleons traveling from the Philippines to Acapulco. |

During the summer of 1579, Drake came ashore somewhere in California to careen his ship to repair the hull. The ship's chaplain complained in his log of "the stinking fogges". |

The nearly omnipresent fog at the Point Reyes headlands throughout the summer, along with the chaplain's descriptions of the inhabitants, the landscape and the wildlife, indicate that Drake's Estero may be the location of Drake's camp. Drake claimed the land for Queen Elizabeth before setting sail southwest to complete his circumnavigation of the globe before returning to England in 1580. |

Chimney Rock |

|

The trail to Chimney Rock climbs past the Historic Lifeboat Station and up a low ridge to the south, over which steep cliffs drop to inaccessible beaches down the peninsula's Pacific flank.The headland is renowned for spring wildflowers, elephant seal colonies and seasonal whale watching. Clear days afford sweeping views of Drakes Beach, Drakes Estero, Limantour Beach and the Farallon Islands. |

The historic Lifeboat Station in Drakes Bay in Point Reyes National Seashore In 1890, alone on the long stretch of empty beach, the Point Reyes Life-Saving Station opened with a crew of eight and a seasoned keeper on a lonely stretch of Great Beach known for its notorious pounding surf and bad weather. Their positions were poorly paid, difficult and full of danger. The surfmen patrolled the beaches of Point Reyes with an ever-vigilant eye, looking for shipwrecks and their desperate crews. They walked the beaches day and night, with the fog chilling them to the bone and the wind blasting sand at the unprotected skin of their faces. |

The view looking west from Chimney Rock |

|

The view looking west from Chimney Rock |

Text |

Chimney Rock is also considered one of the prime wildflower viewing areas in the Bay Area. One finding more different species of wildflower here than in any other place in California. In the spring, this land is a riot of color with magnificent Douglas Irises, California Poppies, Checkerbloom, Indian Paintbrush, yellow and blue lupines, wild cucumber, and more. The short trail to the Elephant Seal Overlook is a great place to see Chimney Rock's springtime display, and more flowers can be seen as you head out on the Chimney Rock Trail. |

Looking west from Chimney Rock The far-distant ridge on the horizon, caught in the the marine layer of fog, is where the Point Reyes Lighthouse is located |

The view looking south from Chimney Rock |

Chimney Rock Chimney Rock caps the easternmost extension of the Point Reyes Peninsula where the Pacific Ocean meets Drakes Bay. |

A curious resident of Chimney Rock |

|

The single lane road, leading to and from Chimney Rock |

Sir Francis Drake Blvd in the Pastoral Lands at Point Reyes National Seashore |

Moss-covered trees along the road to Mt Vision in Point Reyes National Seashore |

|

A view of the Point Reyes National Seashore from the road leading up to Mt Vision |

A view on the trail leading up to the summit of Mt Vision in the Point Reyes National Seashore |

The view of the Point Reyes National Seashore from the summit of Mt Vision |

|

|

Sunset from Mt Vision with Abbotts Lagoon in the middle of the picture |

A view from Mt Vision |

Mt Vision, atop Inverness Ridge at the Point Reyes National Seashore, sports a rounded summit that features extensive views of Drakes Bay and the Pacific Ocean. |

A view from the Pierce Point Road in the Point Reyes National Seashore |

The tail of a skunk moving about in the grasses along the Pierce Point Road |

|

Newsletters Index: 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006

Photography Index | Graphics Index | History Index

Home | Gallery | About Me | Links | Contact

© 2015 All rights reserved

The images are not in the public domain. They are the sole property of the

artist and may not be reproduced on the Internet, sold, altered, enhanced,

modified by artificial, digital or computer imaging or in any other form

without the express written permission of the artist. Non-watermarked copies of photographs on this site can be purchased by contacting Ron.