RON HENGGELER |

October 24, 2024 |

||

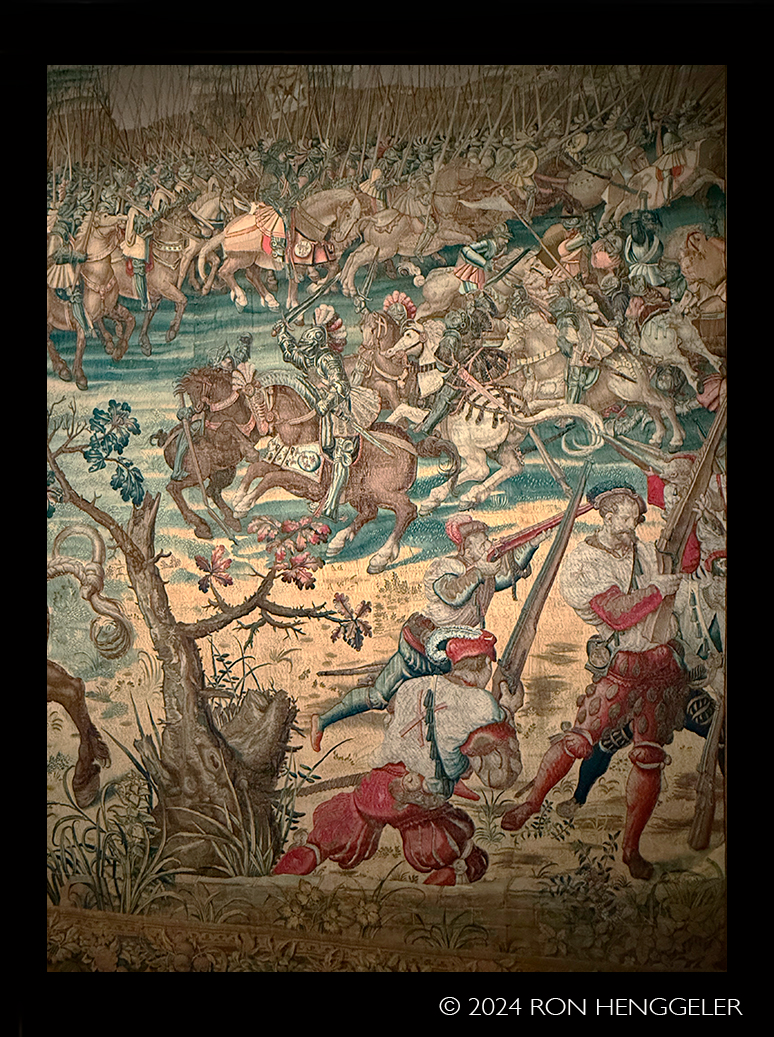

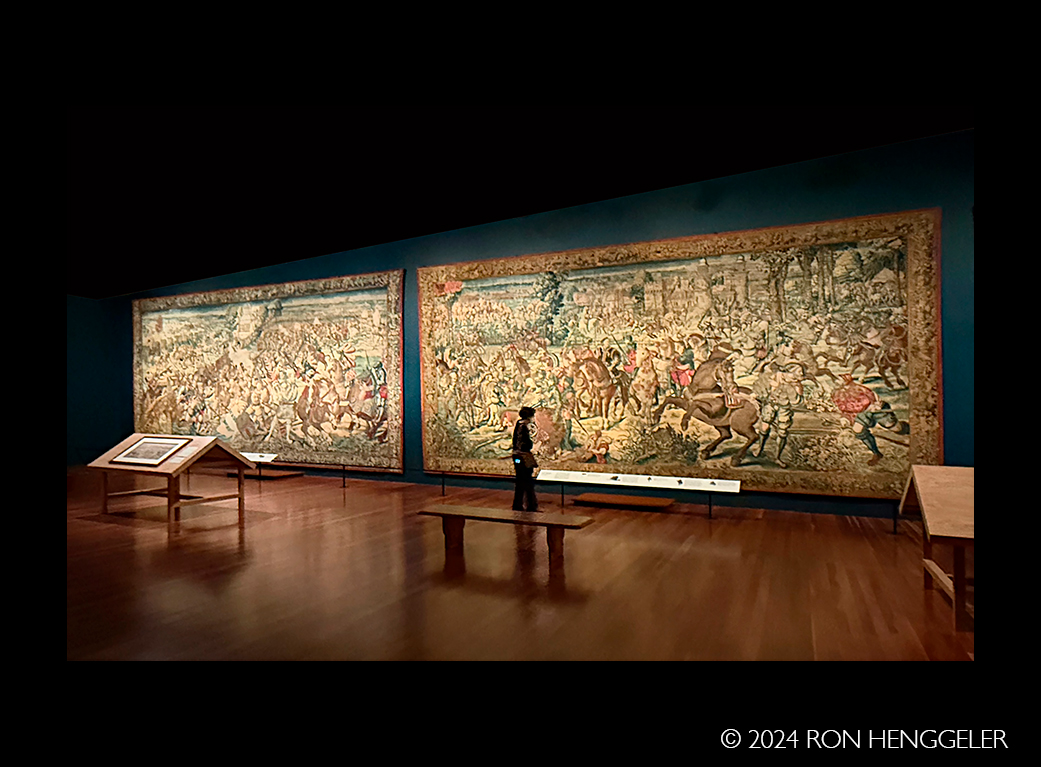

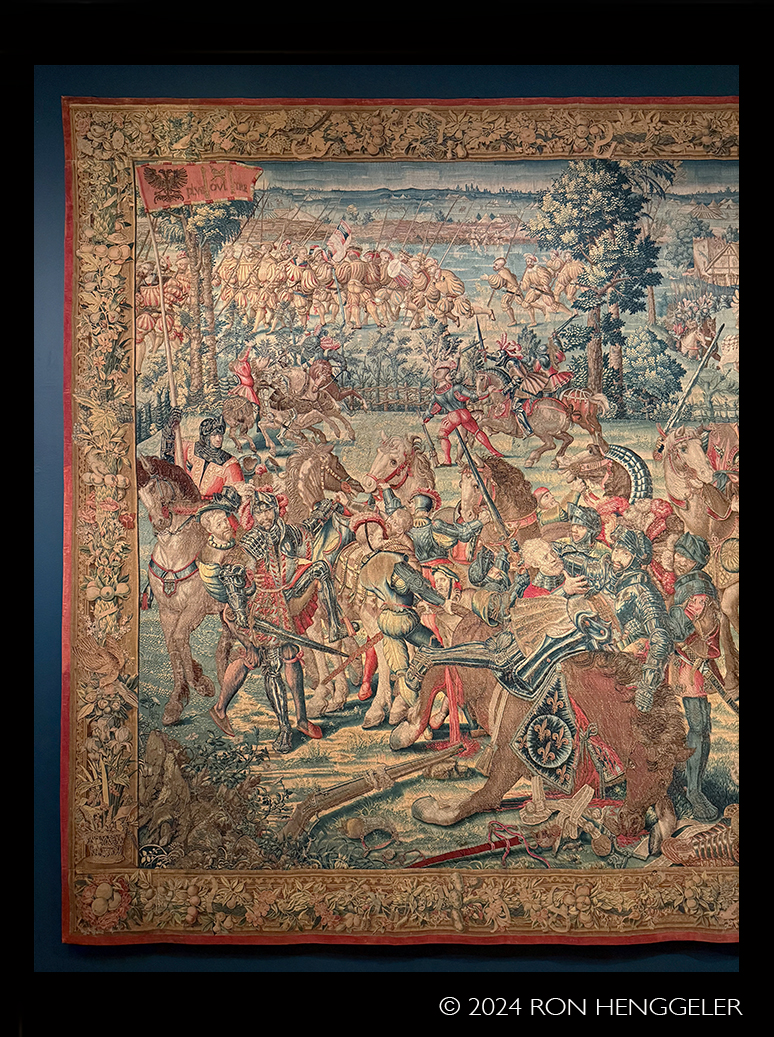

Making their US premiere in Art and War in the Renaissance:This exhibition marks the first time this landmark group of Renaissance tapestries has been on view in the United States. The seven enormous panels, each about 27 by 14 feet, are displayed alongside impressive examples of 16th-century arms and armor. Designed by court artist Bernard van Orley (1487–1541), the Pavia tapestries were groundbreaking creative achievements that incorporated the latest artistic advances. Their vast scale draws viewers into the world of Renaissance politics, technology, and fashion.The Battle of Pavia Tapestries, this landmark group of Renaissance tapestries commemorates Holy Roman emperor Charles V's 1525 victory over the French king Francis I during the 16th-century Italian Wars. Monumental tapestries were among the most prized Renaissance arts and required remarkable feats of collaboration between artists and weavers-a single panel could take over a year to produce. Their vast scale draws viewers into the world of Renaissance politics, technology, and fashion.The text is respectfully taken from de Young |

||

|

||

CHARLES V AND

|

||

|

||

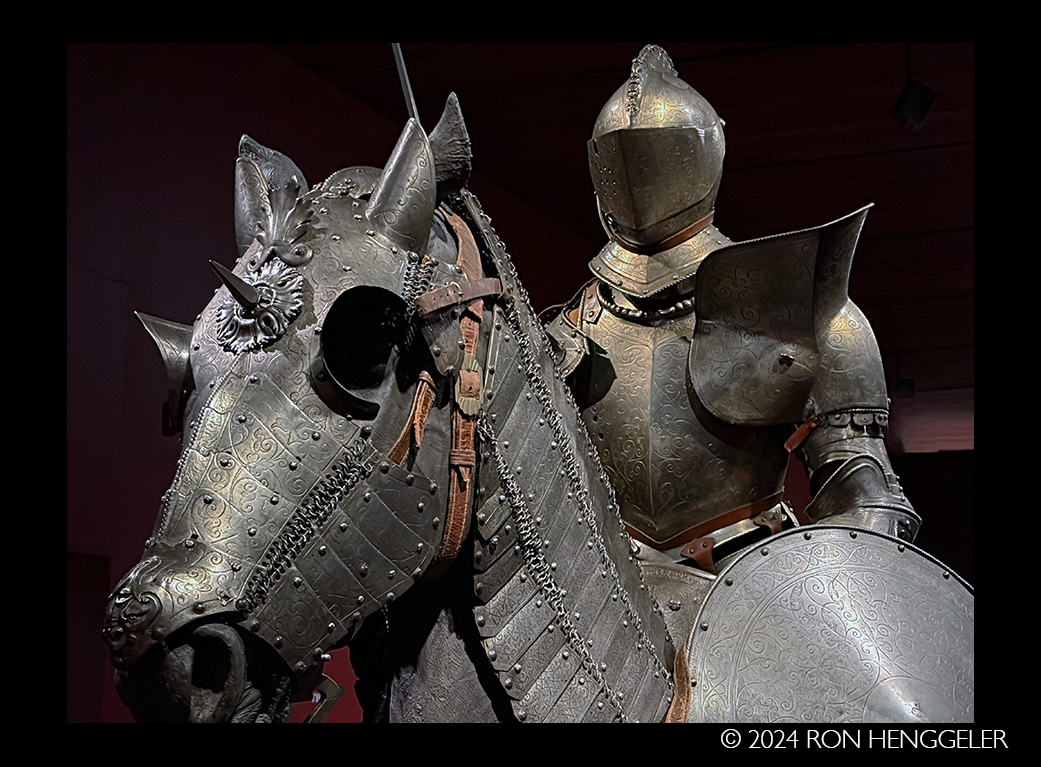

horse in tournament armor ca. 1550-1570 |

||

|

||

Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with

|

||

|

||

|

||

The Advance of the Imperial Army and |

||

|

||

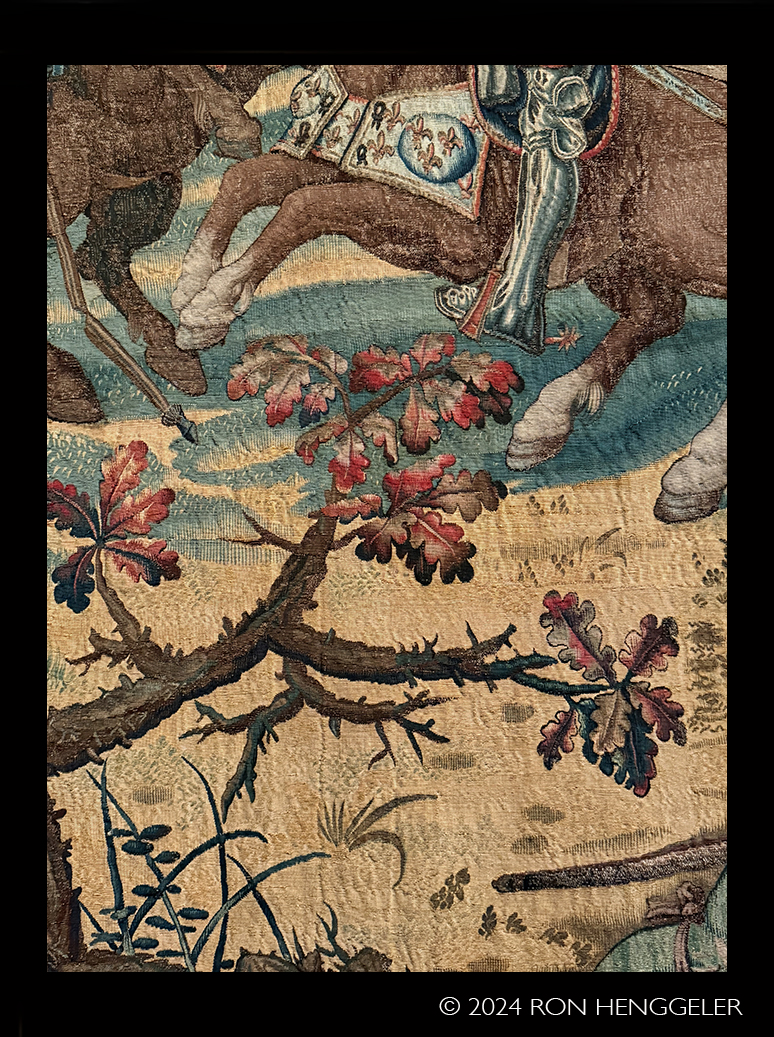

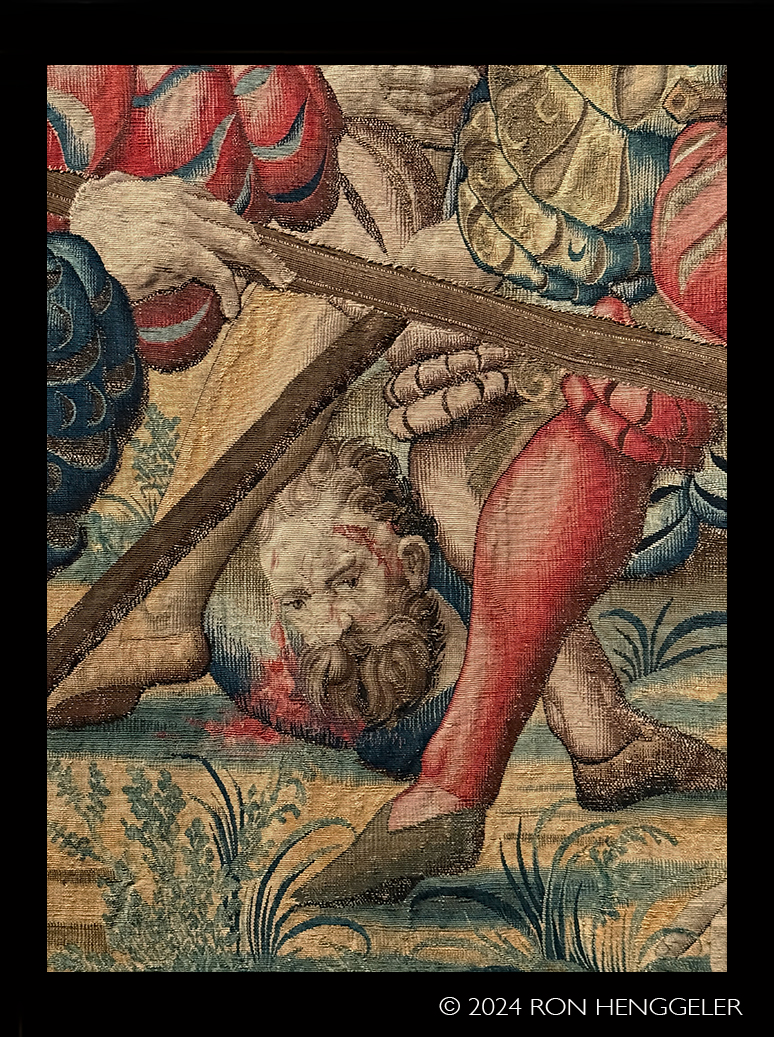

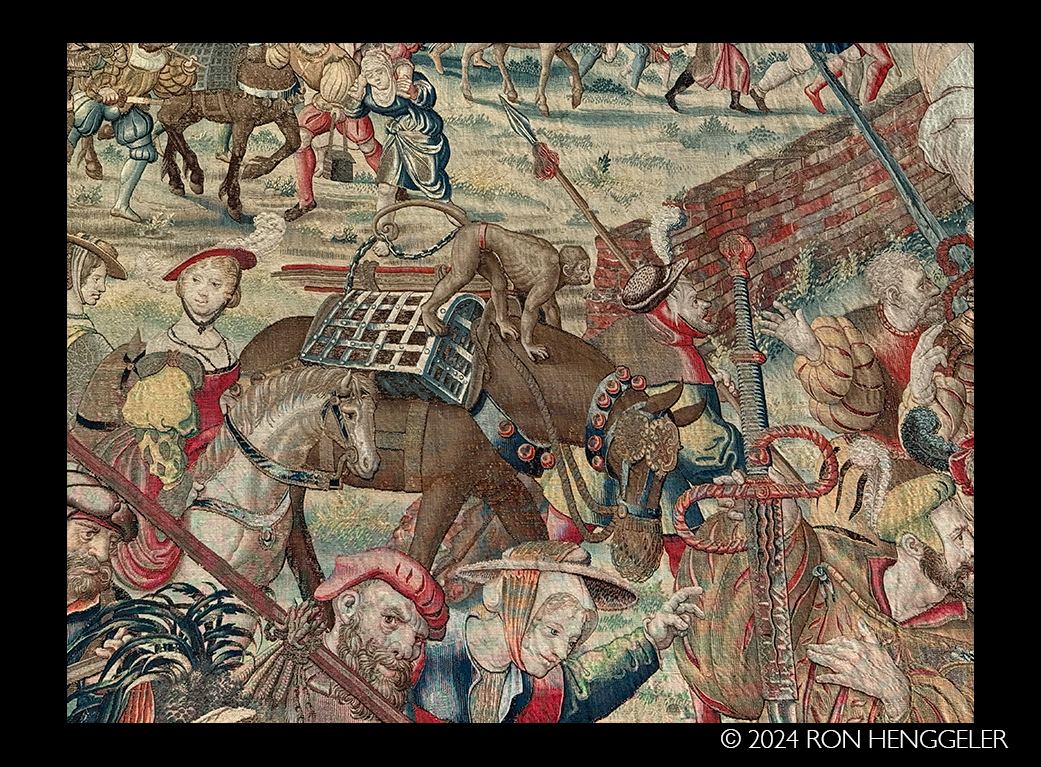

Detail of:The Advance of the Imperial Army and |

||

|

||

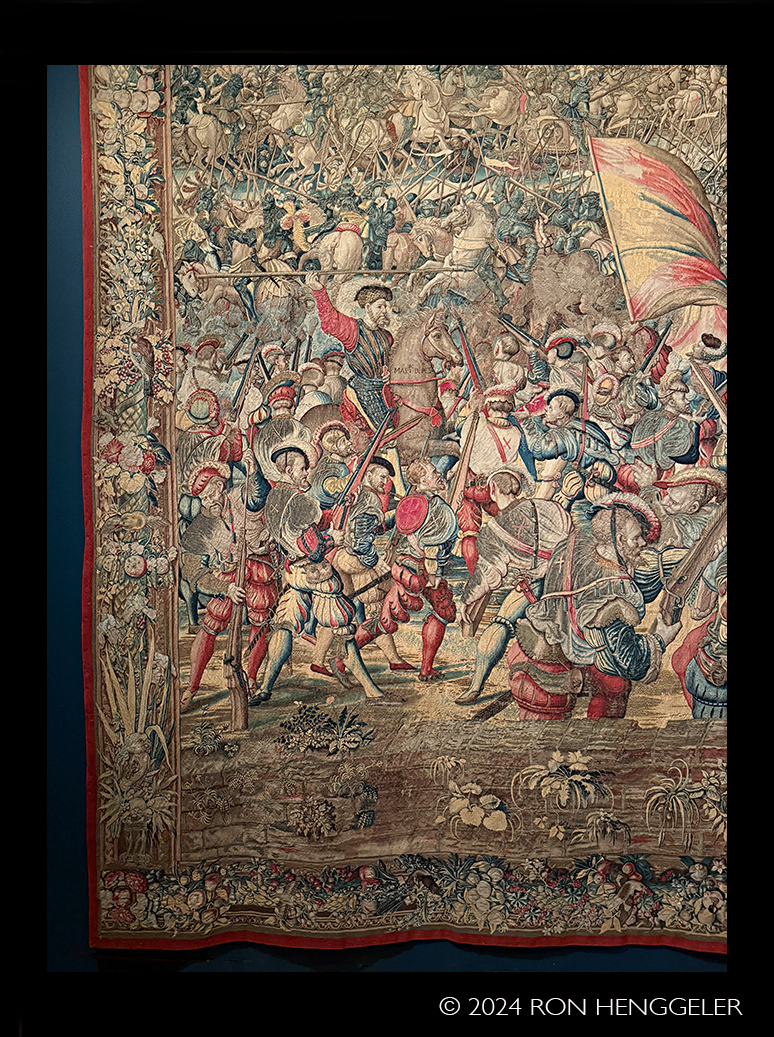

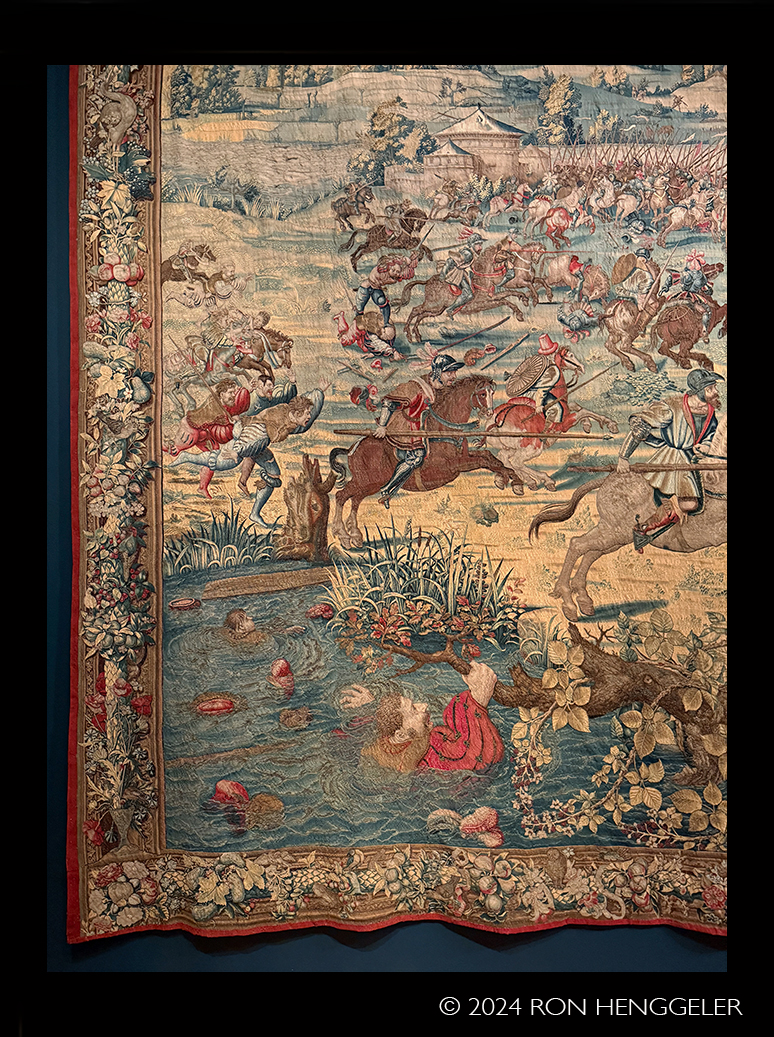

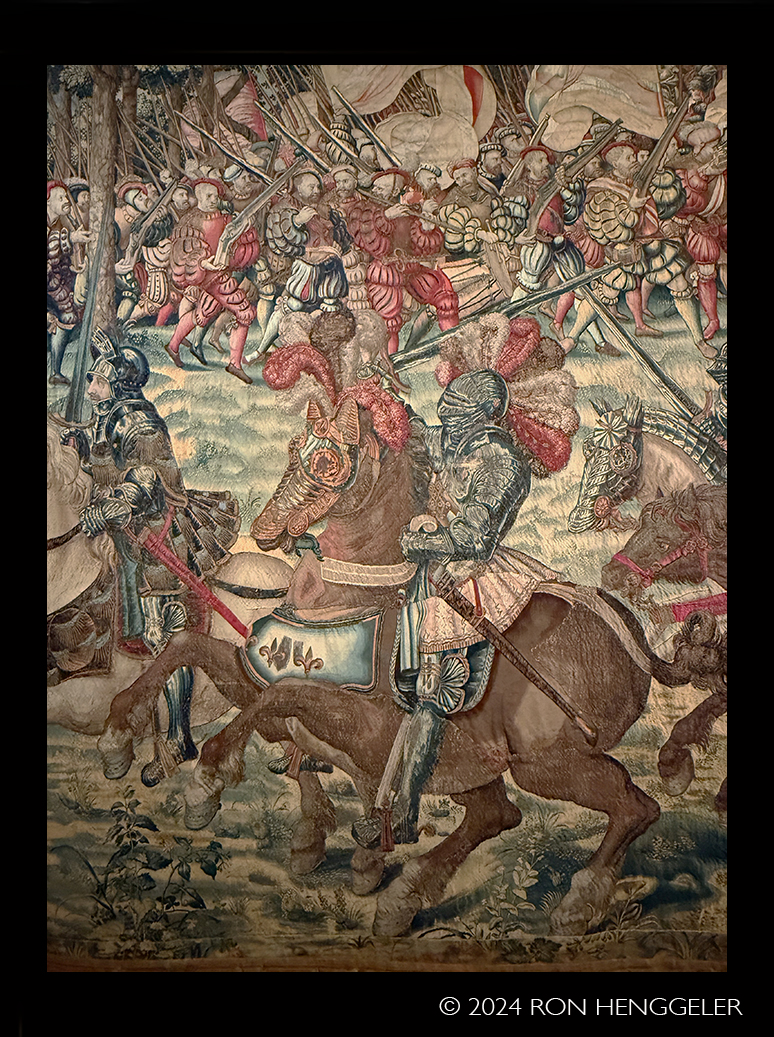

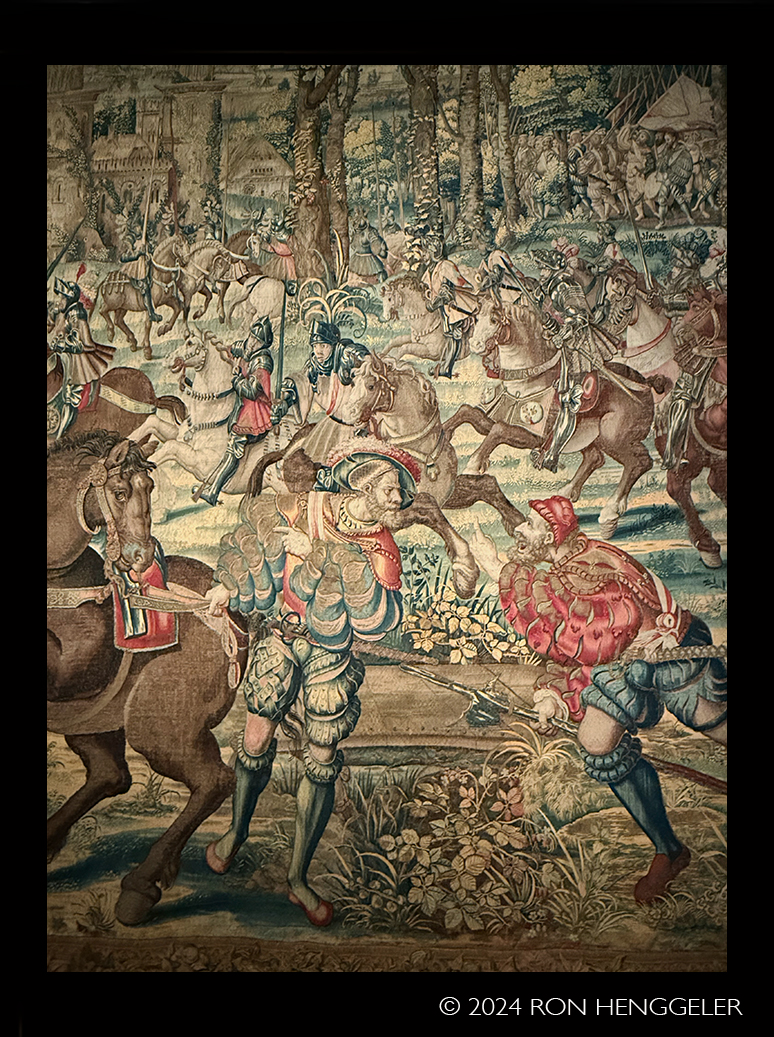

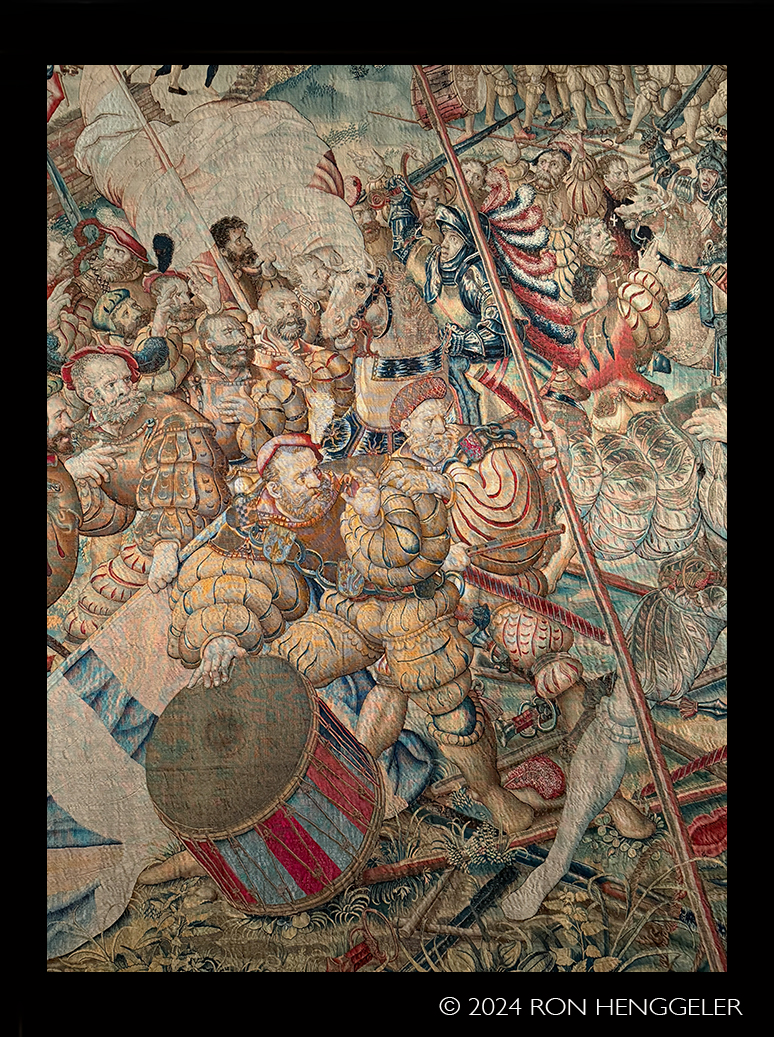

On the right side of the tapestry, in the middle ground, Francis I is depicted at an earlier moment, leading the French cavalry charge. The king-recognizable by the ornate plumage of his helmet, his luxurious armor and clothing, and the fleurs-de-lis that adorn his steed—is followed by his knights. With his sword held high, he prepares to kill his Neapolitan opponent, the Marquis of Civita Sant'Angelo, whose broken lance touches the ground. |

||

|

||

In the foreground of the tapestry, the French heavy cavalry charge forward following the unanticipated imperial attack, led by a knight with an open visor. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

In the lower right corner, are imperial soldiers from the Spanish advance guard, identifiable by the red X-shaped crosses on the white shirts pulled over their doublets, which allow them to be seen in darkness and not mistaken for the enemy by their allies. They aim their arquebuses toward the French cavalry, often targeting the horses and slaughtering large numbers of the enemy. |

||

|

||

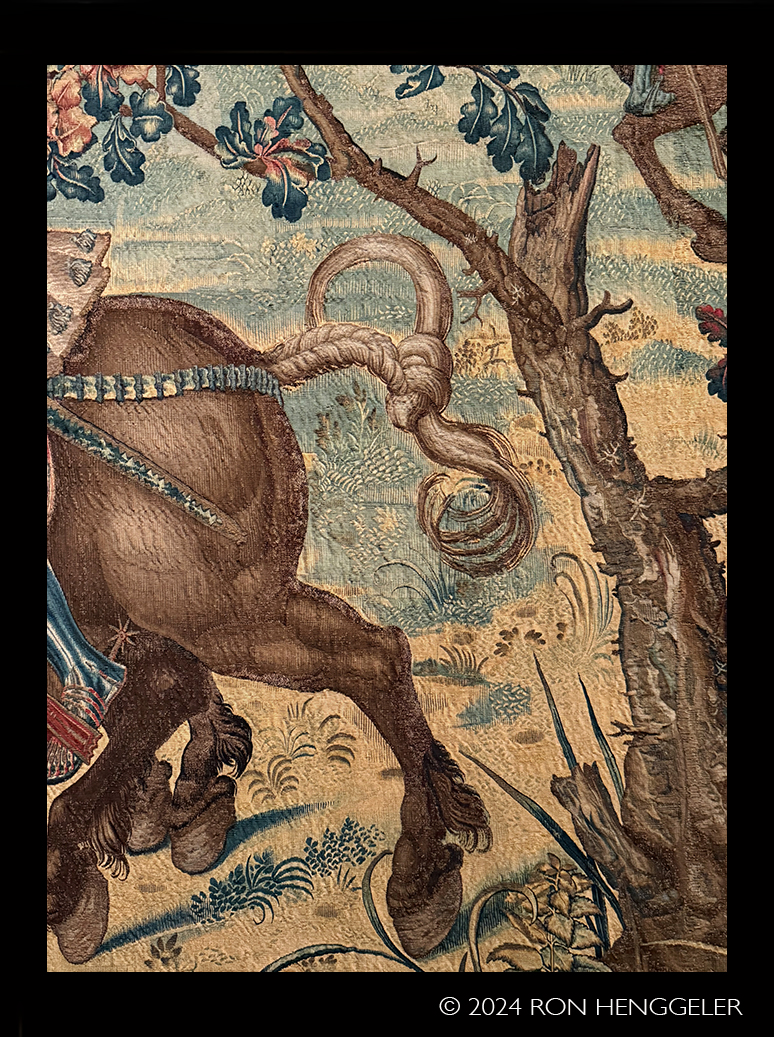

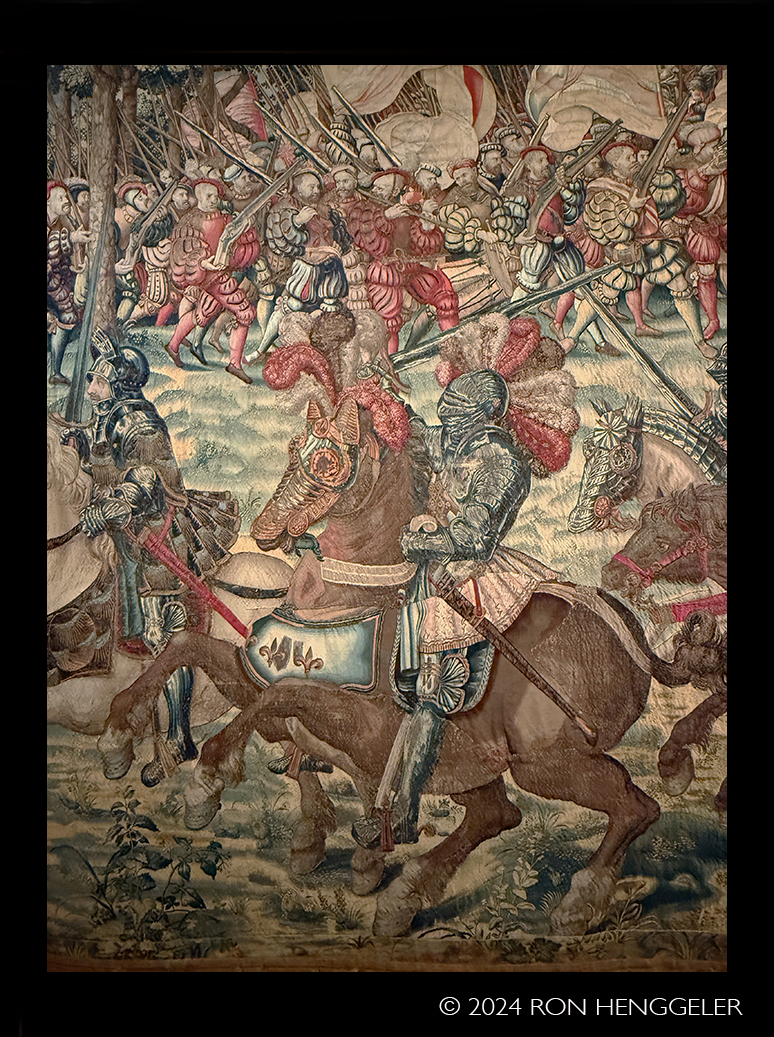

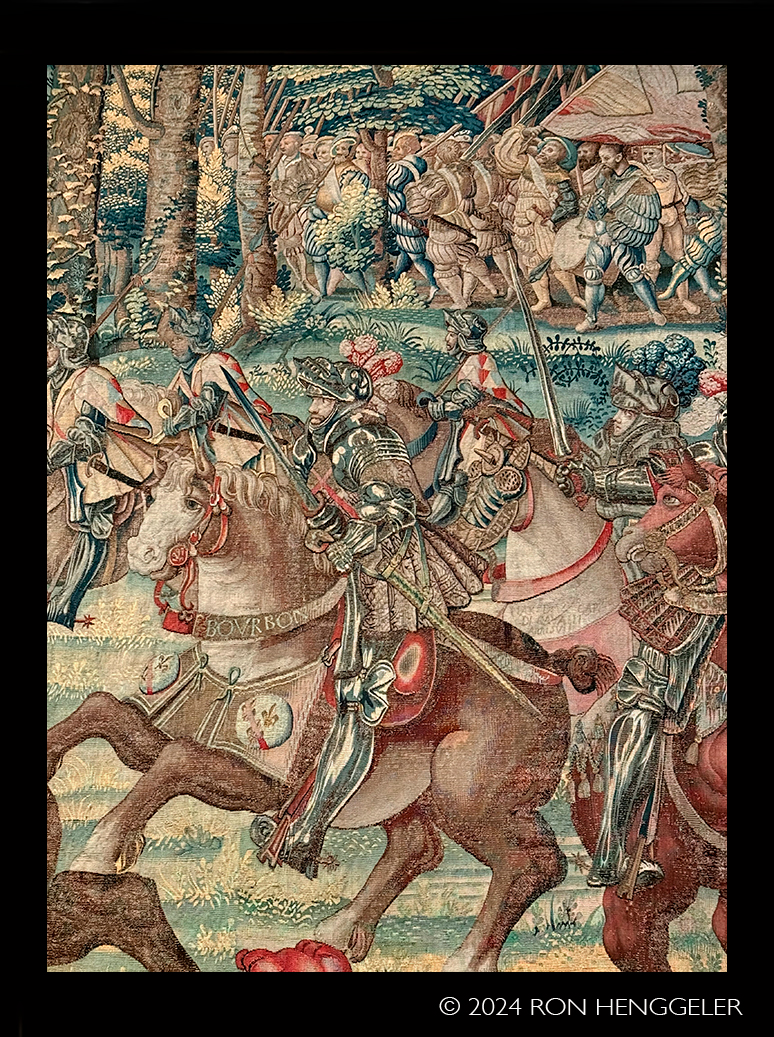

Francis I, wearing a helmet with a grand halo of plumes, rides a horse sporting the royal fleurs-de-lis and an ornate headdress. Behind the king is a trio of illustrious knights, including, at left, Grand Écuyer de France, Galeazzo de Sanseverino, identified by an inscription on his raised sword, who died in the battle, and, next to him, on the brown horse, Antoine de Lettes-Desprez, seigneur de Montpensier, whose title appears on his bridle; he was taken prisoner. The ostentatious trappings of the noble cavalrymen made it easy for the imperial arquebusier — troops using arquebus guns (rifles) - to spot and shoot them in large numbers. |

||

|

||

|

||

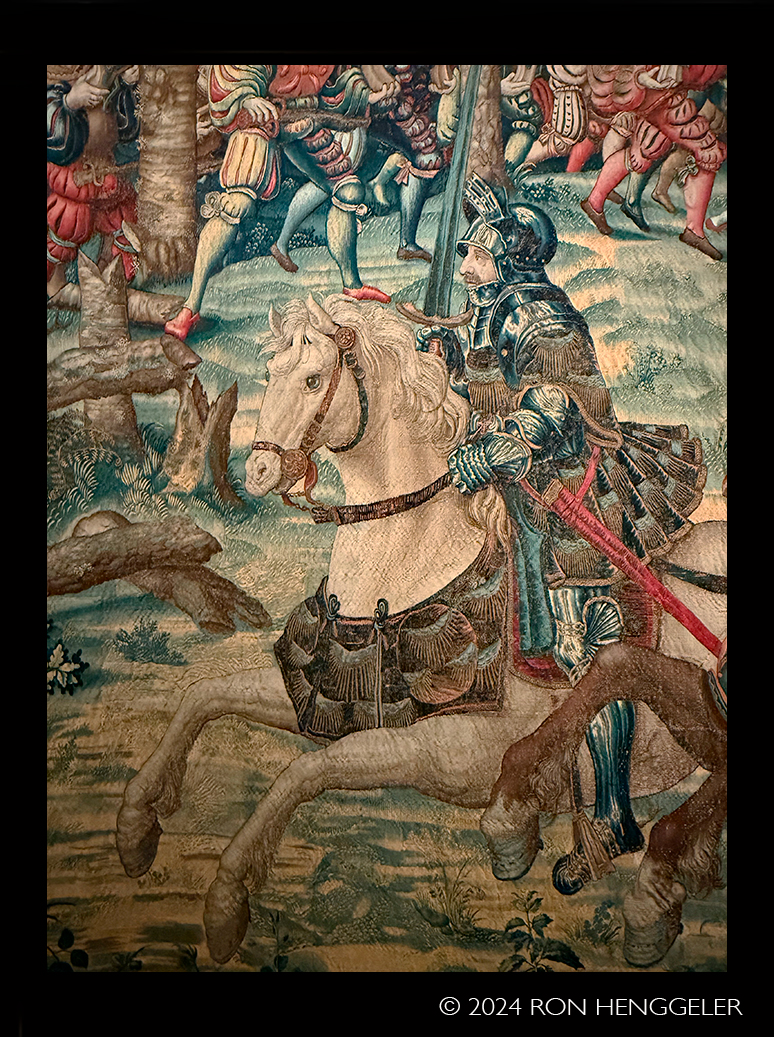

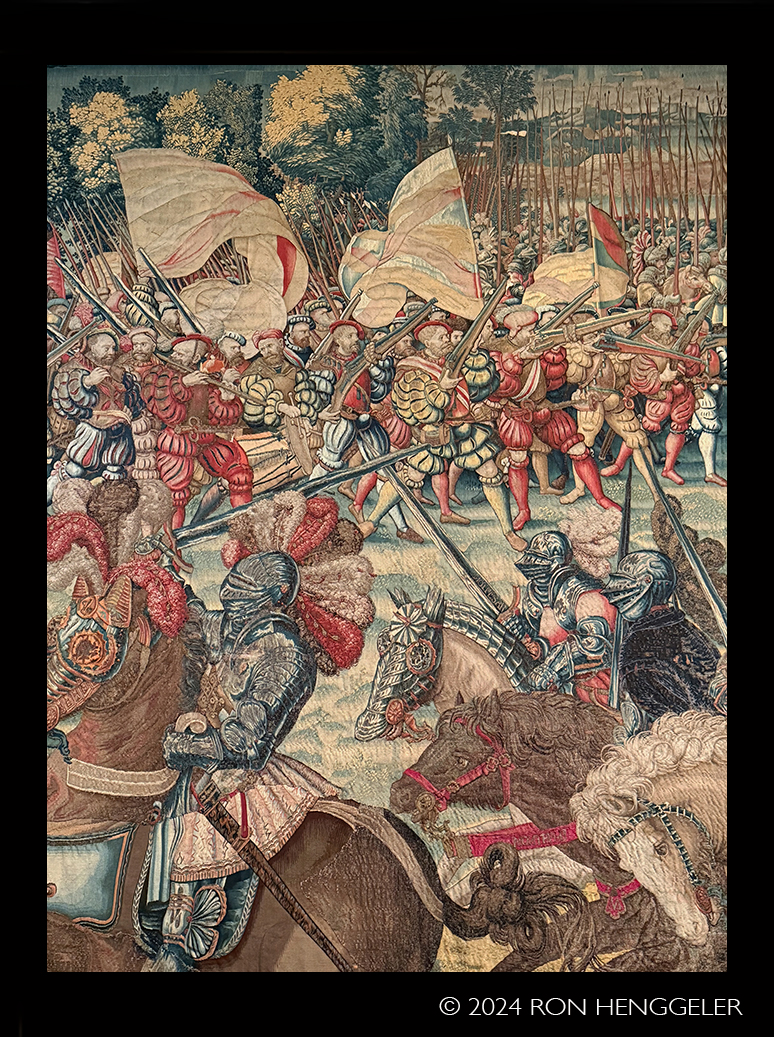

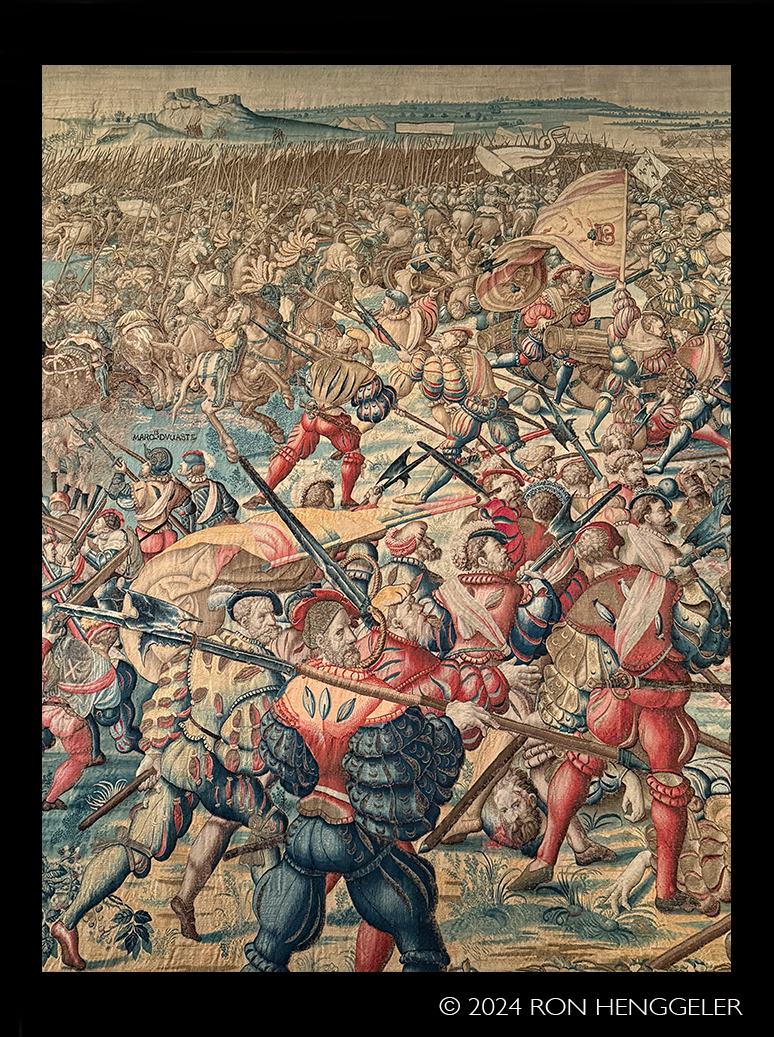

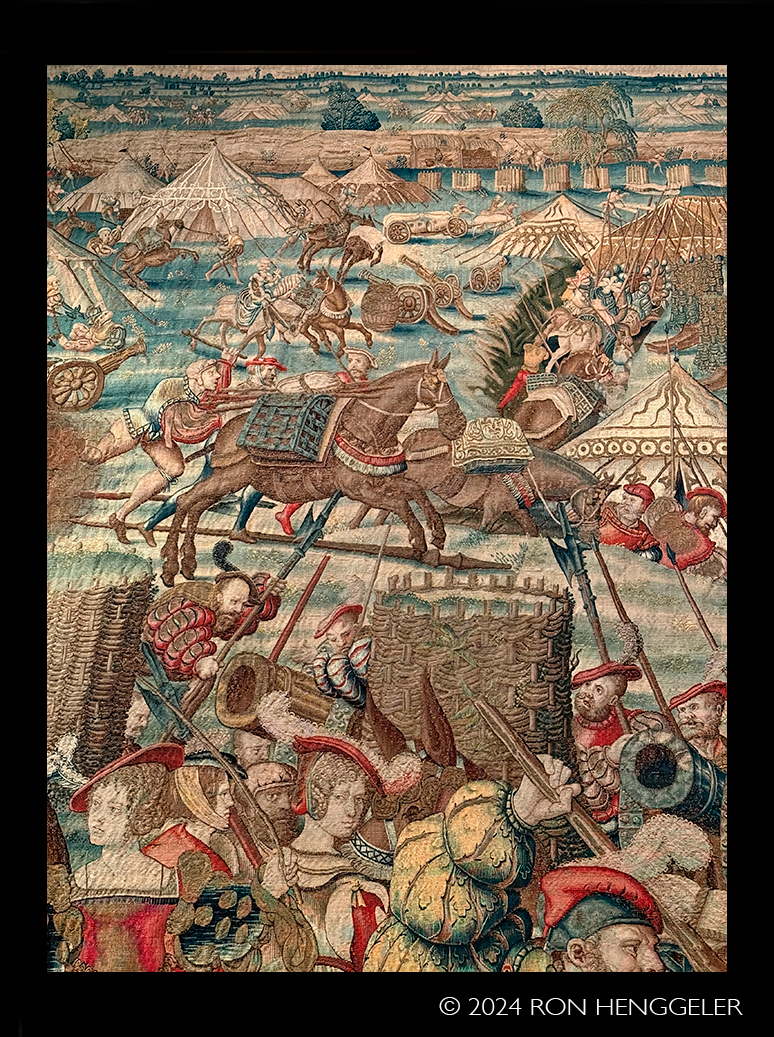

In the front ranks are infantry armed with long-barreled guns called arquebuses, two-handed swords, and pikes. Behind them and in the distance, moving to the right, are the imperial cavalry, carrying lances. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

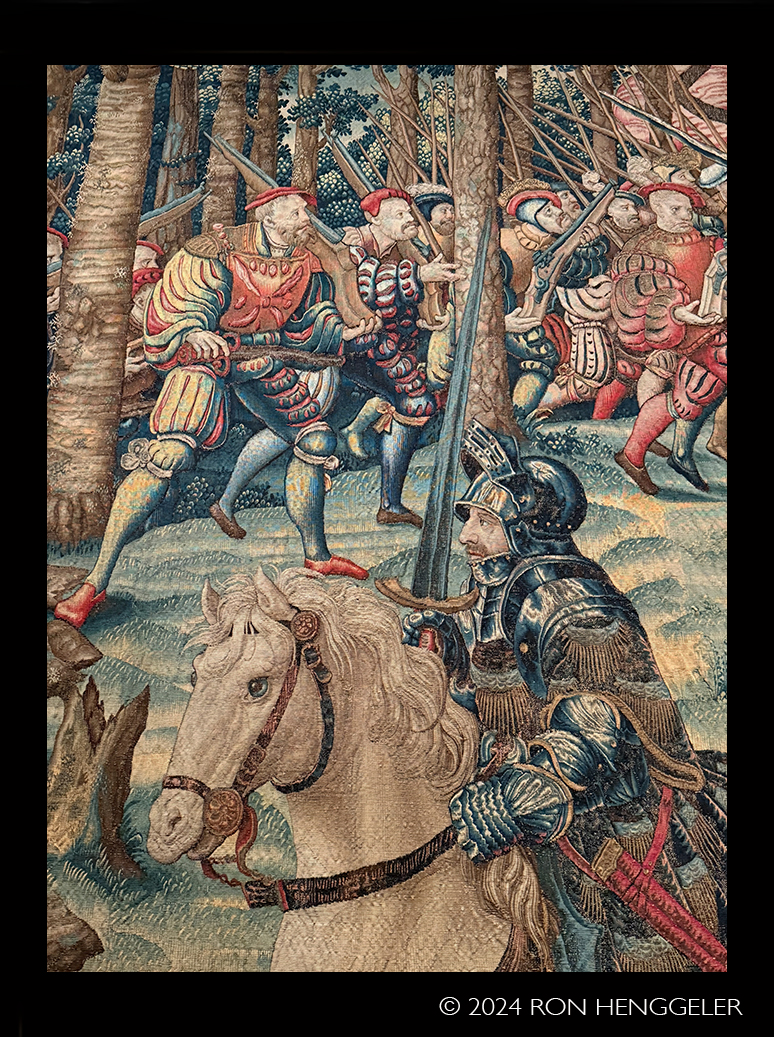

In the background, the imperial army can be seen emerging from the woods at dawn. Raising imperial flags and banners with X-shaped saltires (Saint Andrew's or Burgundian crosses) and the Habsburg colors of red, yellow, and white, the army advances to the cadence of a fife and drum. |

||

|

||

The thick forest of pikes and lances suggests the power and supremacy of the imperial army. Their adoption of a new military tactical maneuver-known as "pike and shot" - enabled the imperial forces to prevail over the formerly invincible French cavalry offensive. |

||

|

||

Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with

|

||

|

||

|

||

Bernard van Orley |

||

|

||

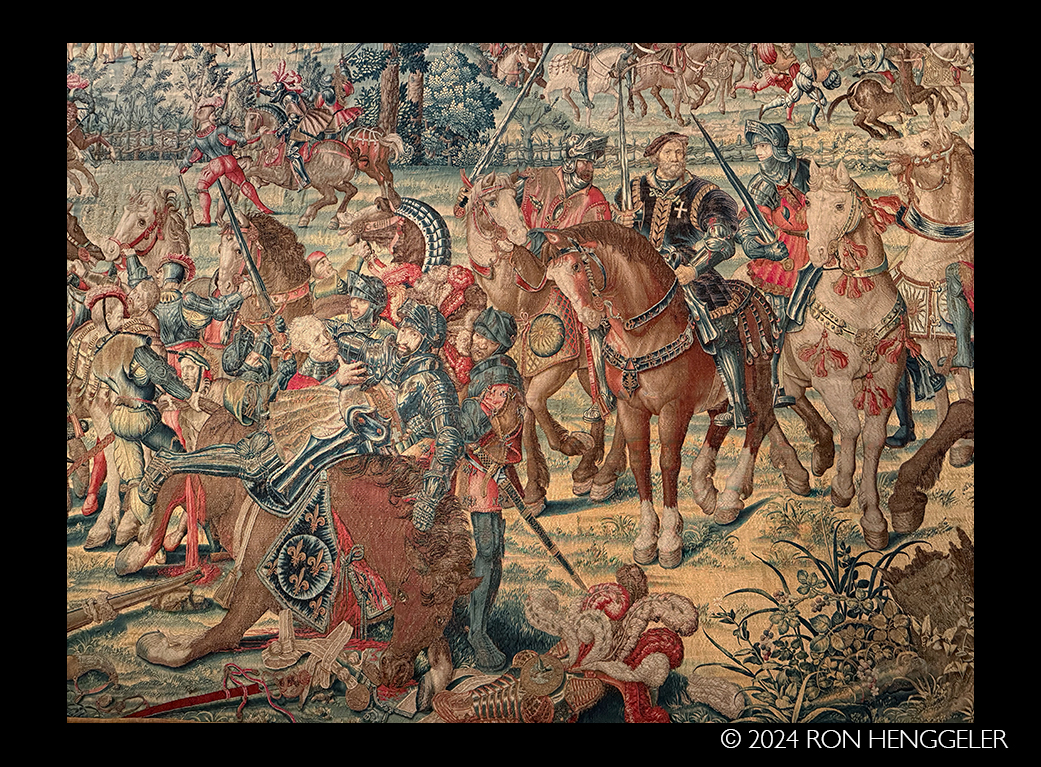

An early stage of the battle is depicted in this tapestry. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Pompeo della Cesa (Italian, ca. 1537-1610) |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

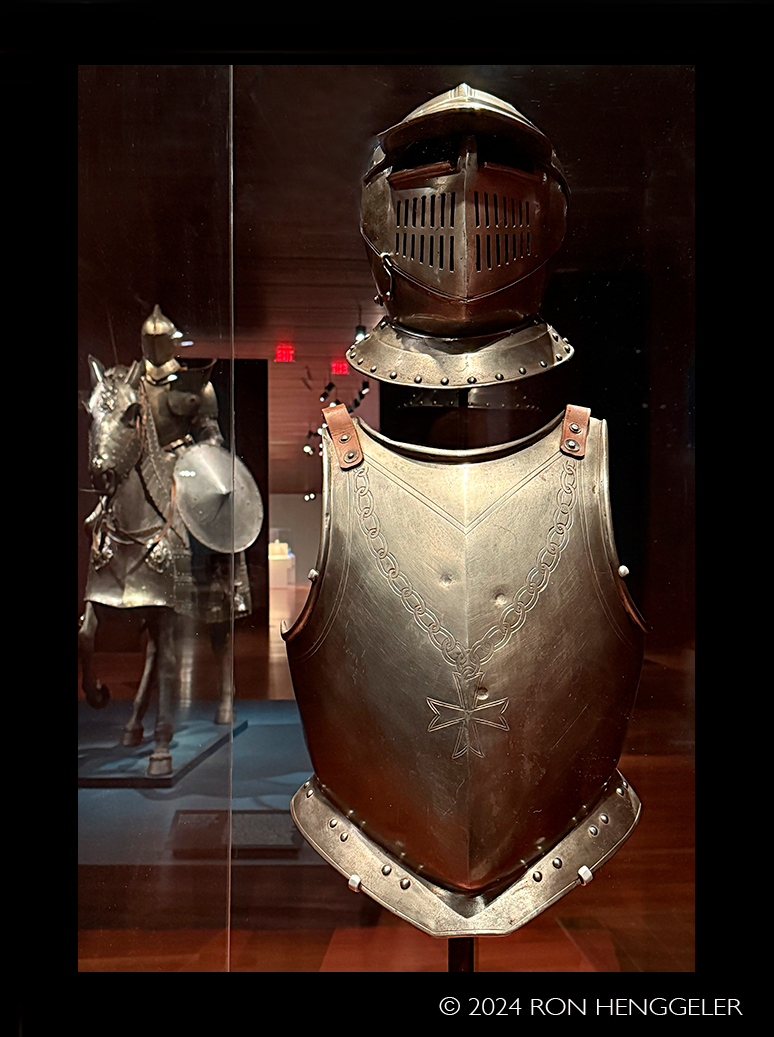

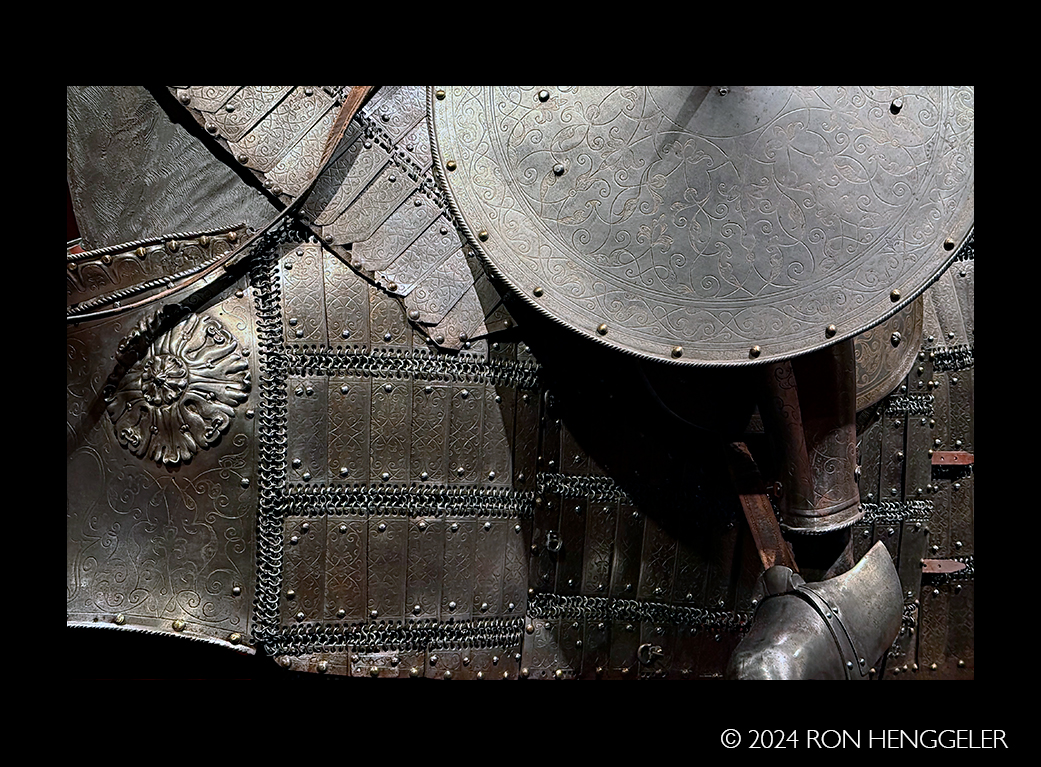

"Medallion" armor garniture,

|

||

|

||

|

||

Francis I, wearing a helmet with a grand halo of plumes, rides a horse sporting the royal fleurs-de-lis and an ornate headdress. |

||

|

||

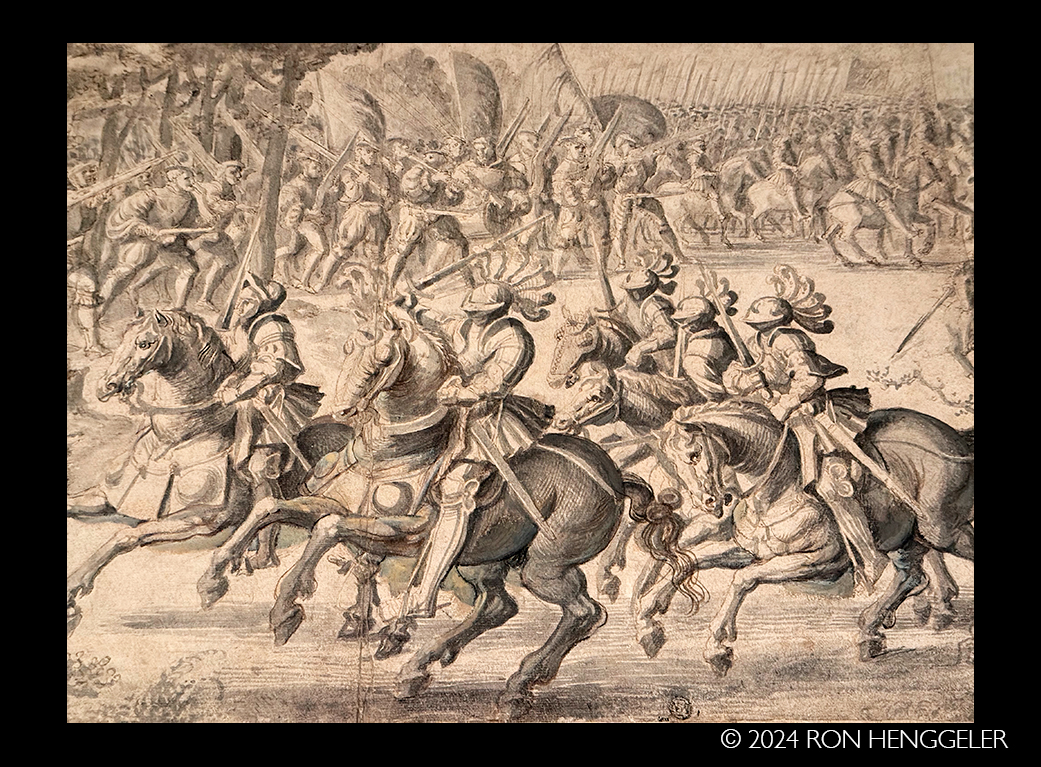

The Presentation Drawings |

||

|

||

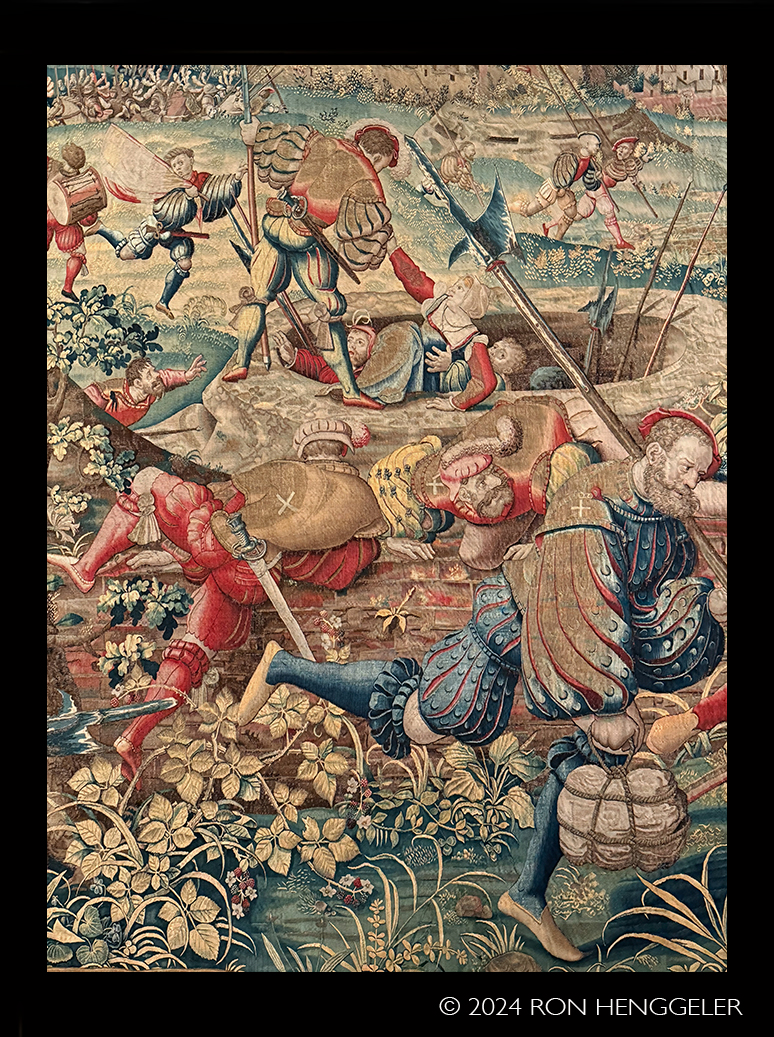

The Imperial Attack on the French Cavalry, Led by the Marquis of Pescara, and on the French Artillery by the |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

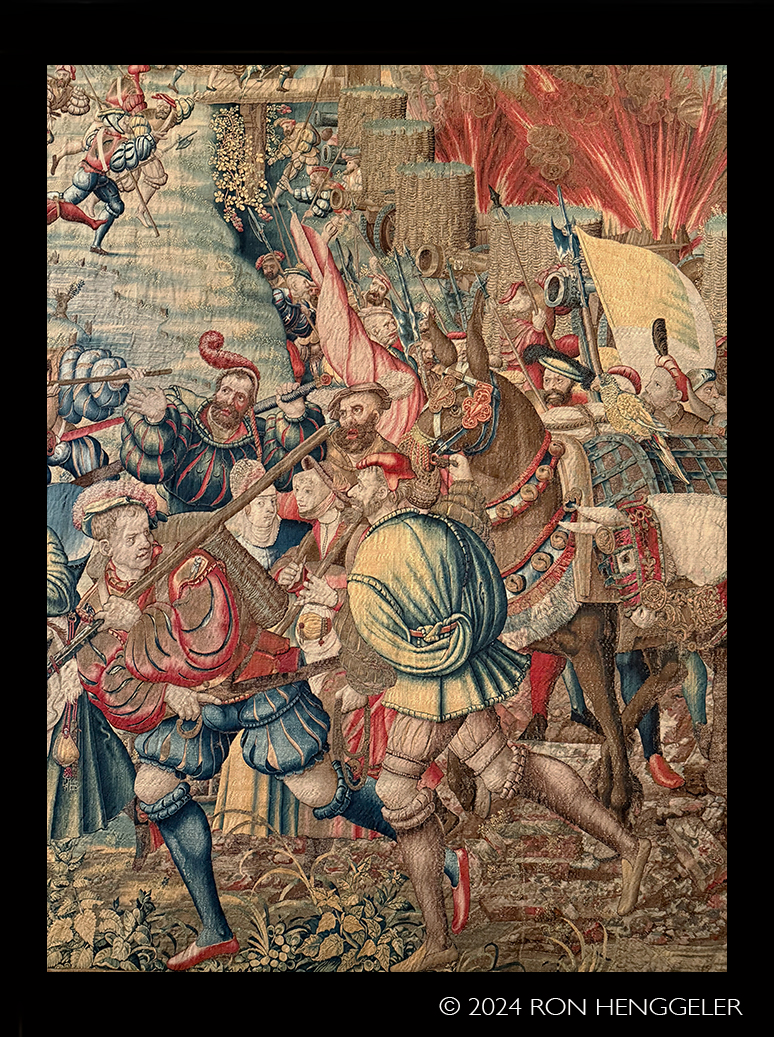

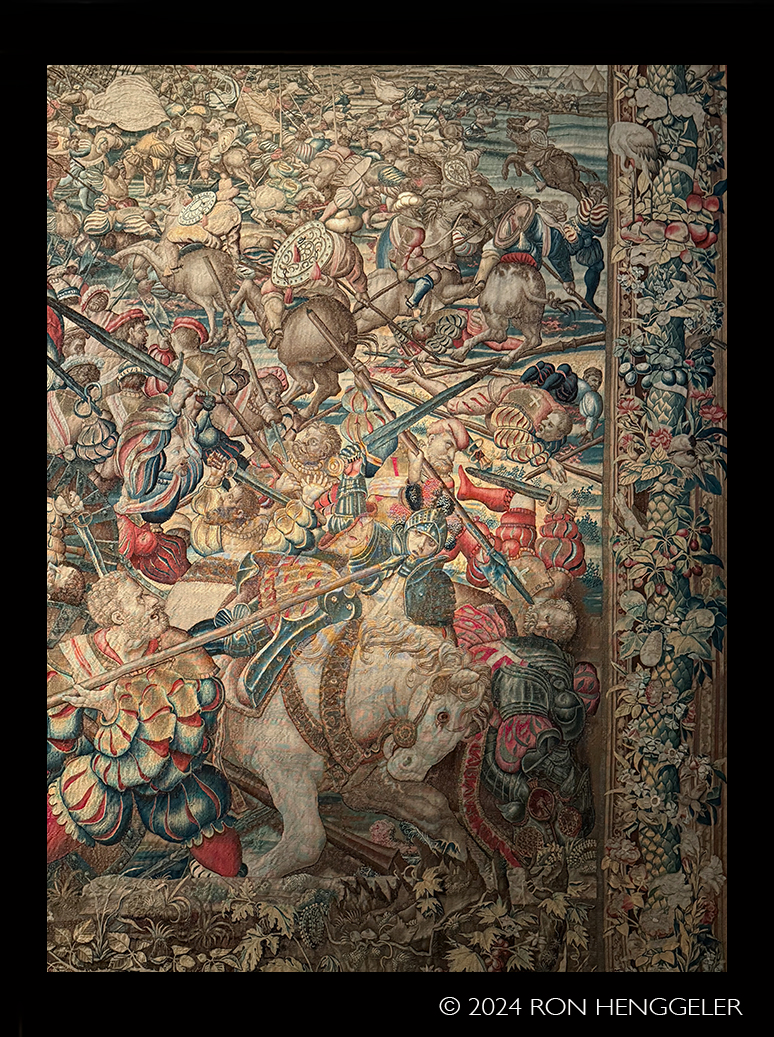

At the far left, a prominent commander in half-armor astride a gray horse wields a lance over his head to signal his men toward the point of attack. An inscription on the neck of his steed identifies him as the Marquis of Pescara, Fernando (or Ferrante) Francesco d'Avalos, who was among the highest ranked in the Habsburg army at Pavia. The d'Avalos family, of Spanish origin, residing in Naples, later owned these tapestries, which were then bequeathed to the Museo di Capodimonte. D'Avalos, like most commanders shown in the Battle of Pavia series, died before the tapestries were completed. It was a great honor for a military leader to appear in a tapestry, establishing his reputation for posterity. |

||

|

||

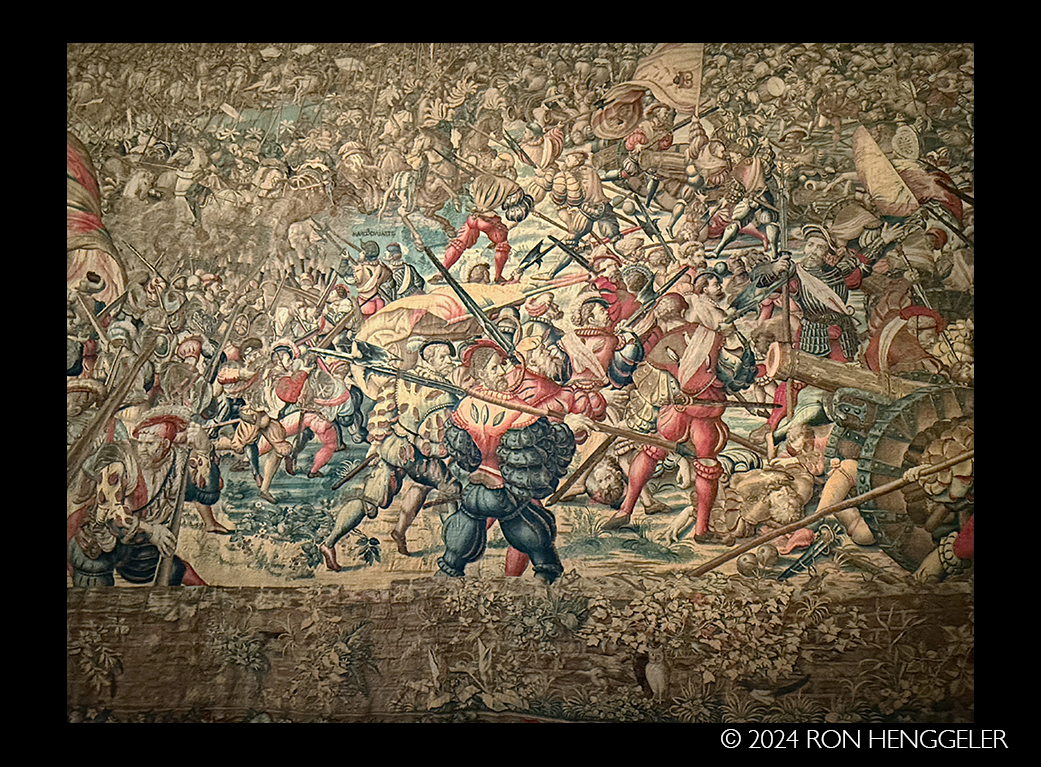

At center right, another key imperial leader is depicted, standing beside a cannon decorated with fleurs-de-lis: Georg von Frundsberg, the formidable commander of the German lansquenets. Holding an upright halberd (a large polearm topped with an axe blade and, often, a hook), he wears half-armor and the imperial white-and-red sash, with his name picked out in gold letters on his sword's belt. Frundsberg triumphantly signals the capture of the French artillery.At the right, Germanic mercenary soldiers called landsknechts, also known as lansquenets, led by Georg von Frundsberg, are recognizable by the white-and-red bands they wear over one shoulder. The landsknechts attack the artillery positions held by renegade mercenaries known as the Black Bands, who have been paid to fight for the king of France. These bitter enemies battle to the death, with the imperial infantry prevailing. In the background, the endless rows of upturned pikes convey the imposing scale of the battle. |

||

|

||

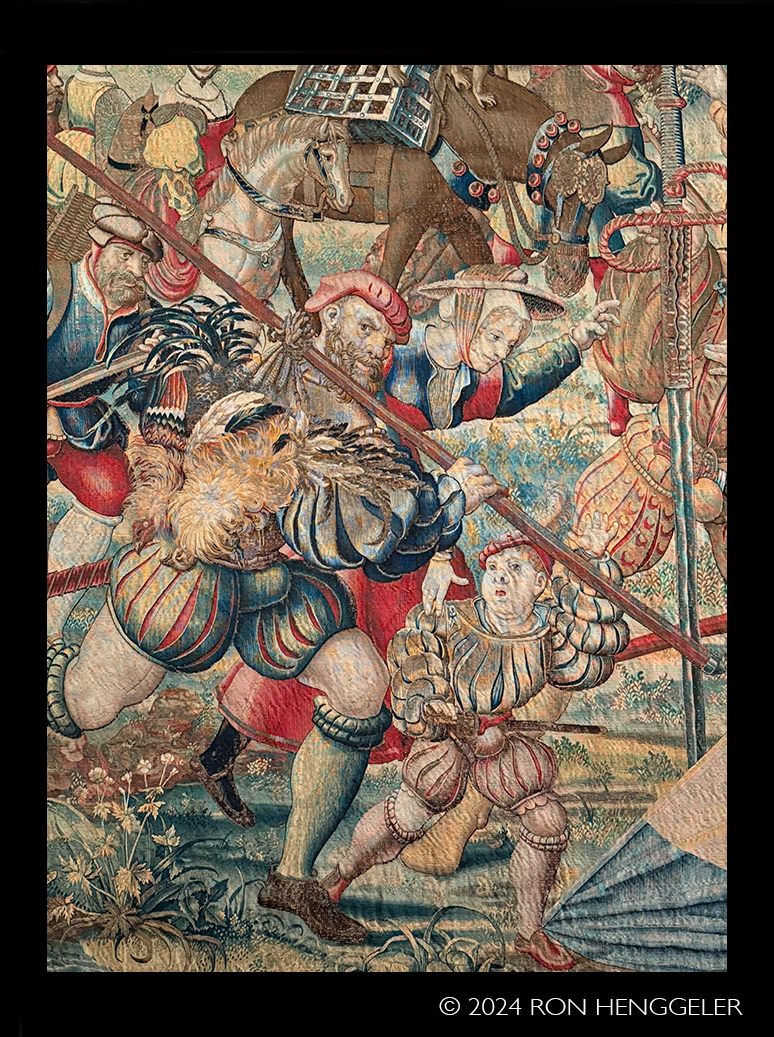

In the middle foreground, we see a prominent figure in dark blue, one of the landsknechts who were critical for the imperial victory. Admired for their skill and bravery, and feared for their ruthless brutality on and off the battlefield, the landsknechts adopted flamboyant and often outrageous dress in a style known as "puffed and slashed." Underlying fabric was pulled through cuts in the outer layers of clothing to create decorative puffs. Billowing sleeves and voluminous or tight breeches created striking, often intimidating silhouettes. In contrast to a more tempered portrayal of elite military commanders belonging to the nobility, tapestry designer Bernard van Orley exaggerated the facial expressions and dynamic physicality of these fearsome mercenaries. |

||

|

||

Detail of: Pompeo della Cesa (Italian, ca. 1537-1610) |

||

|

||

At the center right, another key imperial leader is depicted, standing beside a cannon decorated with fleurs-de-lis: Georg von Frundsberg, the formidable commander of the German lansquenets. Holding an upright halberd (a large polearm topped with an axe blade and, often, a hook), he wears half-armor and the imperial white-and-red sash, with his name picked out in gold letters on his sword's belt. Frundsberg triumphantly signals the capture of the French artillery. |

||

|

||

In thew lower right, we see how violent the clash was between the German lansquenets —identifiable by their white-and-red sashes-and the Black Bands fighting for the French. Many of the dead lie at the foot of the artillery. The commander of the French lansquenets, François de Lorraine, is about to be struck from his white horse and killed by a mighty imperial pikeman. Next to him, in the corner, toppled upon his prone horse, is the armored body of Richard de la Pole, Duke of Suffolk. The inscription LA BLANSE ROSE on his horse's bridle refers to the white rose of the House of York. |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Imperial Attack on the French Cavalry, Led by the Marquis of Pescara, and on the French Artillery by the |

||

|

||

|

||

Farnese guard triple-combed steel helmet, first half of the

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Imperial Attack on the French Cavalry, Led by the Marquis of Pescara, and on the French Artillery by the |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Imperial Attack on the French Cavalry, Led by the Marquis of Pescara, and on the French Artillery by the |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Imperial Attack on the French Cavalry, Led by the Marquis of Pescara, and on the French Artillery by the

|

||

|

||

Horse faceplate,

|

||

|

||

|

||

The Surrender of King Francis I, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

This tapestry depicts the climactic event of the battle: the capture of the king of France by imperial troops. To the left, Francis I is helped off his dying horse-shot with a firearm-by imperial military officers. At the far left, Charles de Lannoy, viceroy of Naples and commander of the imperial army, dismounts to accept the surrender of the king of France.In the upper left corner, the Habsburg emperor's banner soars high. The red flag displays the Habsburg double-headed eagle alongside Charles V's personal insignia, featuring the Pillars of Hercules and the motto "Plus Ultra" (Further Beyond), here written in French: Plus Oultre. |

||

|

||

|

||

Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Surrender of King Francis I, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Surrender of King Francis I, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with

|

||

|

||

|

||

The swords raised high by the horsemen in the center of the tapestry denote imperial victory. Francis I was imprisoned in Italy and then taken to Spain. He was released upon signing the 1526 Treaty of Madrid that abandoned French claims to the duchies of Milan and Burgundy and other important territories— terms he broke shortly thereafter. Although hostilities resumed, Habsburg ascendancy in Europe and beyond was determined at the battle of Pavia. |

||

|

||

In the left foreground unfolds the battle's climactic scene: the defeat of the French king. The wounded and disjointed body of Francis I is freed from his dying horse by three imperial captains identified with inscriptions: |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Surrender of King Francis I, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with |

||

|

||

At center, the bearded figure, who has been variously identified, may be another depiction of Charles III, the Duke of Bourbon, present at Francis I's capture (also seen in the detail at right). The raised swords denote victory and are mentioned in contemporary accounts, as is Bourbon's honorable and deferential treatment of Francis I. Following the battle of Pavia, in 1527 Bourbon accompanied the imperial troops south to Rome to relay Charles V's warning to the pope to come to his terms. |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Surrender of King Francis I, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

|

||

At the far right, Charles III, Duke of Bourbon— identified by the inscription BOURBON and fleurs-de-lis on the horse's trappings-breaks into a gallop. |

||

|

||

The Invasion of the French Camp and the Flight of the Women and Civilians, |

||

|

||

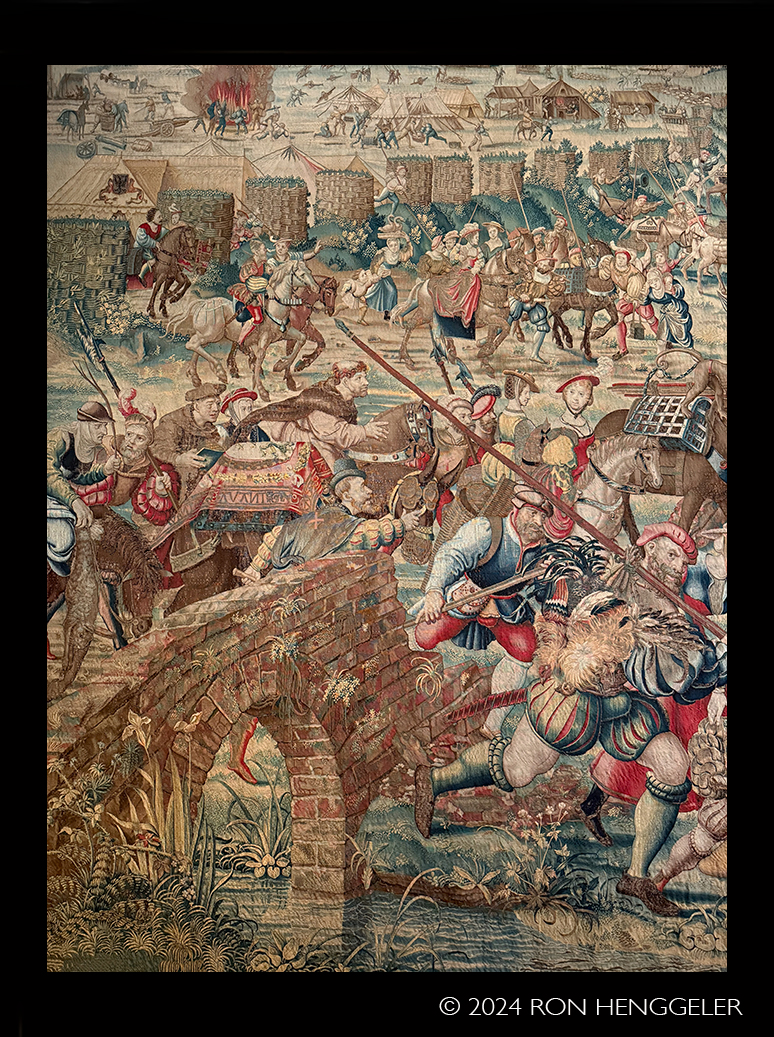

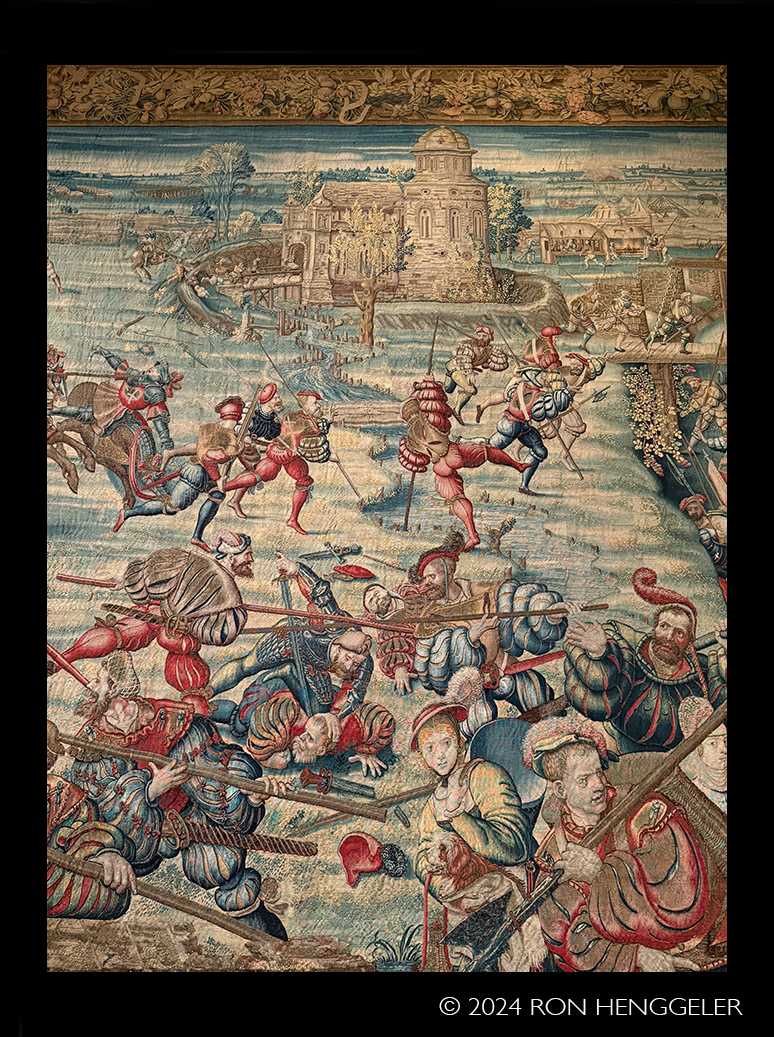

In this tapestry, the imperial forces storm in from the left to capture the French headquarters, overwhelming all resistance. Below, to the right, French soldiers are deployed in two trenches, protected by cannons between wicker-clad emplacements called gabions. The imperial cavalry has already invaded the camp and broken through the second line in pursuit of the French, who take flight into open ground. In the foreground, alarmed civilians in the French army's retinue — family members, auxiliaries, and orderlies-flee to safety in several directions, carrying what they can gather. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Attributed to

|

||

|

||

In the left foreground, a burly landsknecht wields a hefty double-handed sword to break the pike of his opponent. Such elite, experienced soldiers - armed with huge double-bladed swords, or with halberds (polearms topped with an axe blade and, often, hooks used to unmount horsemen), or with the long firearms called arquebuses —were known as"doppelsoldner" since they received double pay. The landsknechts paid for their clothing and armor — here an impressive set of half-armor with chain mail protecting the chest. Above this group of infantry, imperial cavalry and Germanic pikemen attack the besieged French troops, and a French horseman, identifiable by his white cross, is killed with a lance. |

||

|

||

At the top left stands Mirabello Castle, and at the top right is the French camp, composed of white tents. Also at the top left of the tapestry stands Mirabello Castle, near two trenches that protect the French artillery. Its drawbridge is down, allowing the imperial troops, identifiable by their white-and-red sashes, to storm the camp. |

||

|

||

In the center of the scene, toward the back, weavers have managed the difficult feat of representing fiery explosions in the French encampment, driving soldiers and mules to scatter. We see the French deployed in two trenches, protected by their artillery positioned between gabions. Critically for the outcome of the battle, none of the French cannons are firing. Although the French had an advantage with their numbers of large guns, they had an inadequate supply of ammunition, and their flawed strategy prevented them from using the artillery, which would have struck their own troops. At the end of the battle, the French artillery was a significant part of the war booty obtained by the imperial troops. |

||

|

||

Detail of:

|

||

|

||

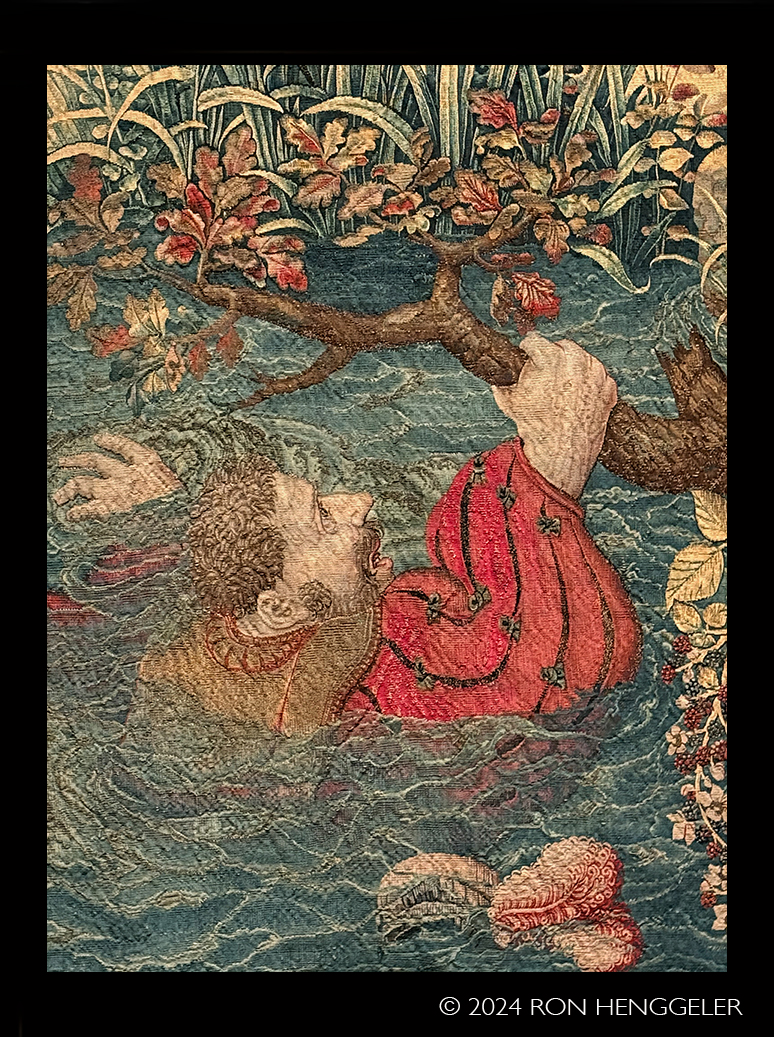

In the foreground, the French baggage train— civilians in the French army's retinue, including family members of the combatants, vendors, porters, cooks, orderlies, and others who attended to the army's daily operations-begins to flee to the right and left. Led by a bounding hound, a young woman— purse and keys hanging from her waist— escapes with a fluffy dog. |

||

|

||

Also part of the baggage train, an elegant lady in a red velvet robe — perhaps a French officer's wife or a courtesan—rides sidesaddle on a white mule with a lavish harness. Details of her fashionable dress, like the puffs of contrasting fabric pulled through slits in the blue sleeves, are meticulously described. Likewise notable are the trappings of the brown mule in front of her, such as the fine net muzzle, the bells and fringe of the harness, and the golden parrot perched on a trunk above the saddle. |

||

|

||

|

||

At the top left of the tapestry stands Mirabello Castle, near two trenches that protect the French artillery. Its drawbridge is down, allowing the imperial troops, identifiable by their white-and-red sashes, to storm the camp. To its right sit the white tents of the French encampment. A golden tent decorated with fleurs-de-lis-just behind the huge explosion that scatters mules and soldiers in different directions— probably housed the king. It, too, was sacked by Spanish infantry, and the Marquis of Pescara took the tent itself as a war trophy. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

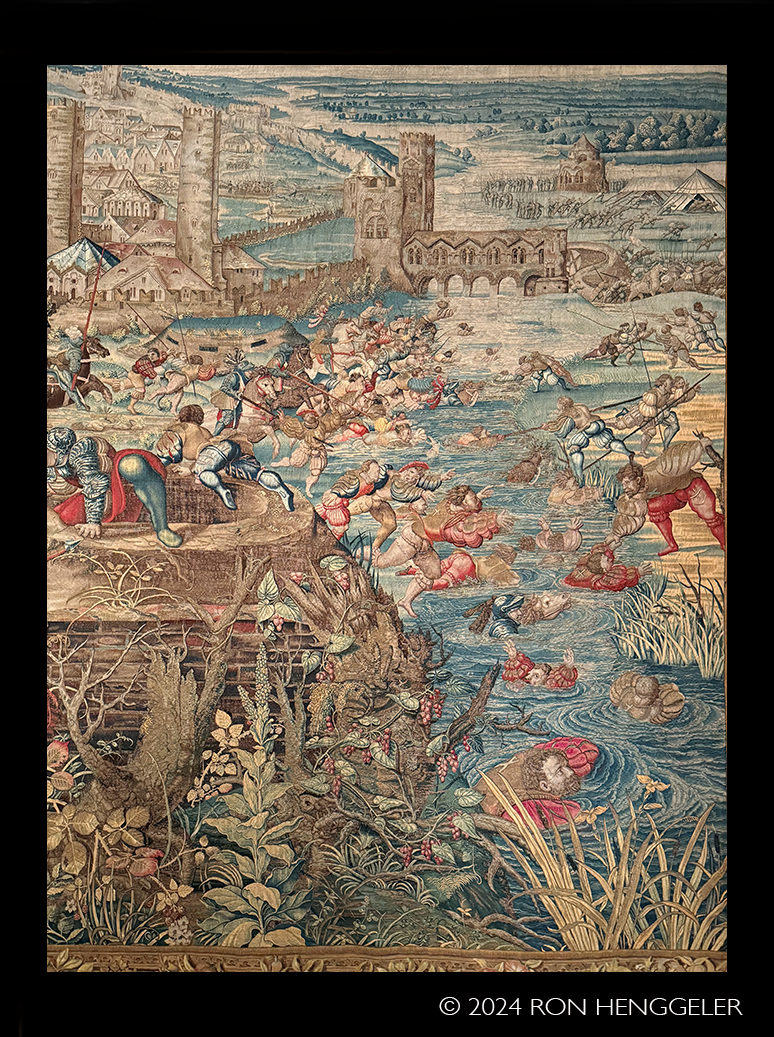

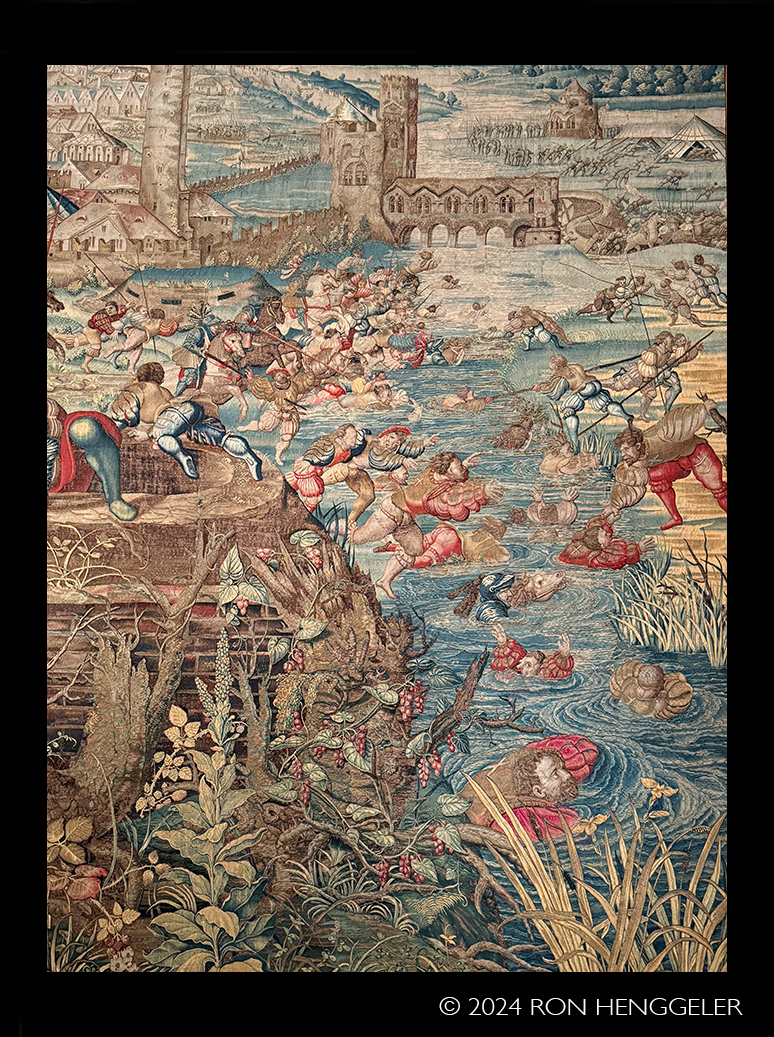

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

At the upper left is Visconti Castle, the garrison commanded by the Spanish captain Antonio de Leyva, whose soldiers had resisted the French siege for four months. De Leyva's troops make a sortie from the city and strike what remains of the enemy. A Swiss infantry unit, quickly routed, bears the brunt of the Spanish sortie. |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

Farnese guard triple-combed steel helmet, first half of the |

||

|

||

At the lower left corner, two soldiers in extravagantly plumed hats are ready to join their compatriots as they scramble over a brick wall to escape the Spanish imperial onslaught. One soldier wields a double-handed sword marked with a white cross over his shoulder and the other, in half-armor, bears the French flag. Most infantry were pikemen, but the most skilled soldiers ("doppelsoldner") wielded halberds (large double-handed swords or polearms topped with ax blades), which they used to penetrate the enemy's pike formation. |

||

|

||

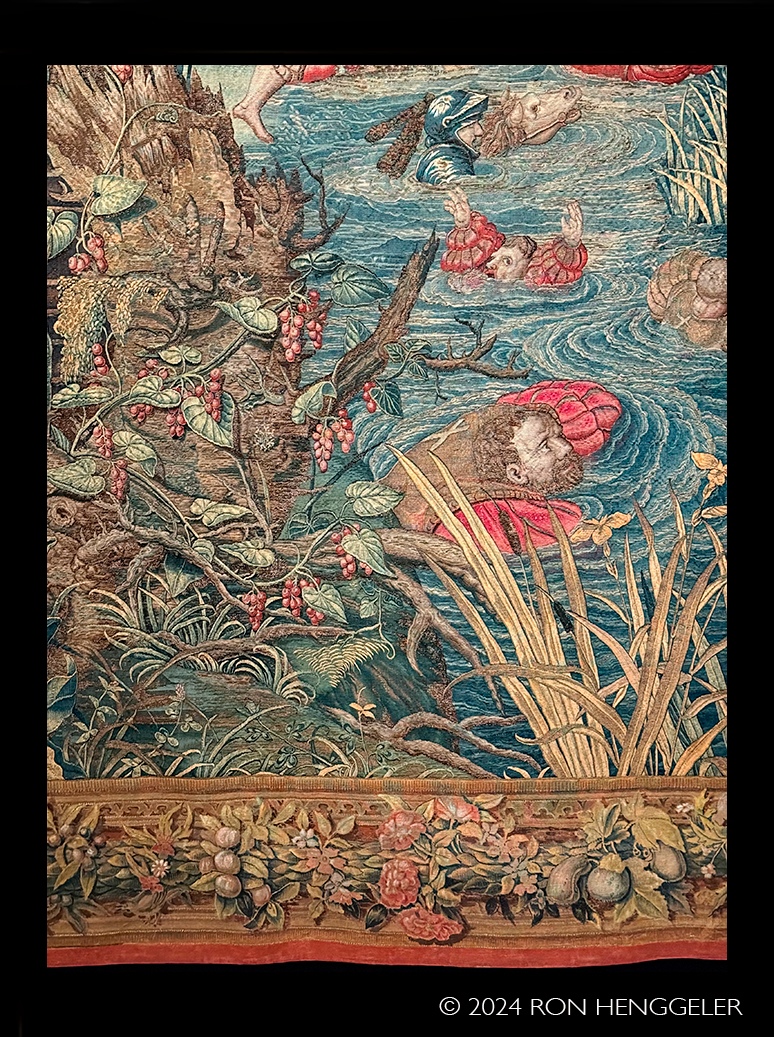

Through details in the background we see how the tapestry weavers used fine gradations of color to carry the eye into the distant hills and valleys to create this panoramic, bird's-eye view of Pavia and its environs— an astonishing achievement in the medium of tapestry. Bernard van Orley's design captures the aftermath of the battle in striking detail, from the frenzied soldiers navigating the Ticino River to the covered bridge and city ramparts to the calm of the countryside. |

||

|

||

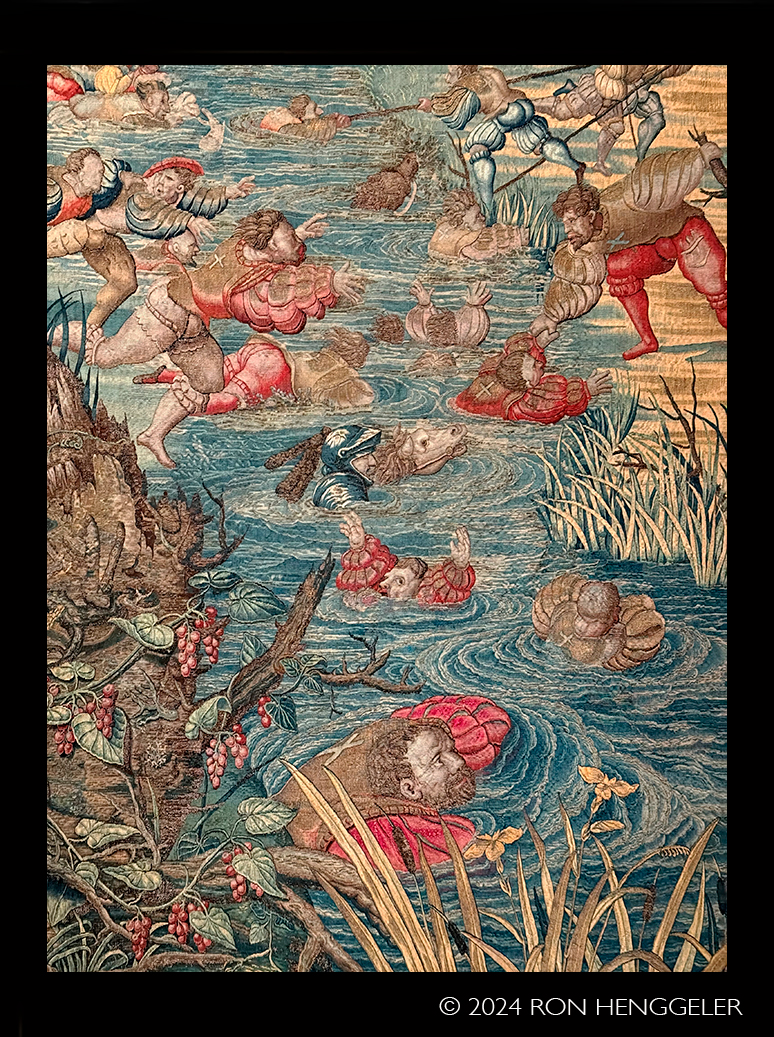

Along the right side of the tapestry flows the Ticino River, with members of the Swiss infantry fleeing toward it for safety. However, upon reaching the riverbank, they discover that the pontoon bridge has been destroyed by the Duke of Alençon, who has already escaped. At this point, the Swiss have no choice but to throw themselves into the rising waters of the river, and many perish by drowning. The weavers show remarkable skill carrying out tapestry designer Bernard van Orley's highly detailed composition, teeming with closely observed plants and figures in animated poses. |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

In the middle ground of the tapestry, French soldiers and civilians emerge from some of the encampment's protective dugouts in an effort to quickly escape from these now unsafe positions. Nearby are two French horsemen, one of whom is identified as François de Laval, Count of Montfort, by an embroidered inscription on his horse's bridle reading MOFORT. He is listed among the dead at Pavia. |

||

|

||

D'Avalos armor helmet, ca. 155°

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Sortie of the Besieged Imperial |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

|

||

At lower left, a soldier desperately clings to a branch to save himself from drowning, as feathered berets and discarded weapons float by. Elements that can be seen beneath the rippling water, such as the soldier's body, showcase the masterful skill of the weavers to replicate painterly detail and illusionistic effects. Their sophisticated and varied weaving techniques required using a high warp count and ever-finer shades of dyed silk and wool to capture subtle color variations such as the veins of the soldier's hand. |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531At right, the French rear guard, stranded on the bank of the Ticino River by enemy cavalry, seeks to escape by crossing the river on a pontoon bridge. On orders of the Duke of Alençon, the pontoon bridge is destroyed to prevent the imperial soldiers from pursuing the fleeing soldiers. A French foot soldier in red unmoors the bridge from the left bank of the river with his halberd (a large polearm combining an axe blade and, often, a hook), as two soldiers-one carrying a drum and broken pike and the other the Swiss flag— rush toward safety. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531In the background, in the upper part of the tapestry, the bucolic landscape with fields of grazing herds of cattle and gentle wooded hills —more Flemish than Italian in inspiration-suggests a world of peace and safety remote from the horrors of war shown in the battlefield. |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

Overwhelmed by the unstoppable Spanish breakthrough, Charles IV, Duke of Alençon, brother-in-law of Francis I and commander of the French rear guard, leaves his position and, instead of engaging in combat, retreats to the other side of the Ticino River, shown at far right. In France, his actions will lead to accusations of cowardice and treachery, although his tactics ensured the survival of his troops. With his red lance held skyward, a French horseman rushes to cross to the other side of the Ticino River before the bridge is destroyed. |

||

|

||

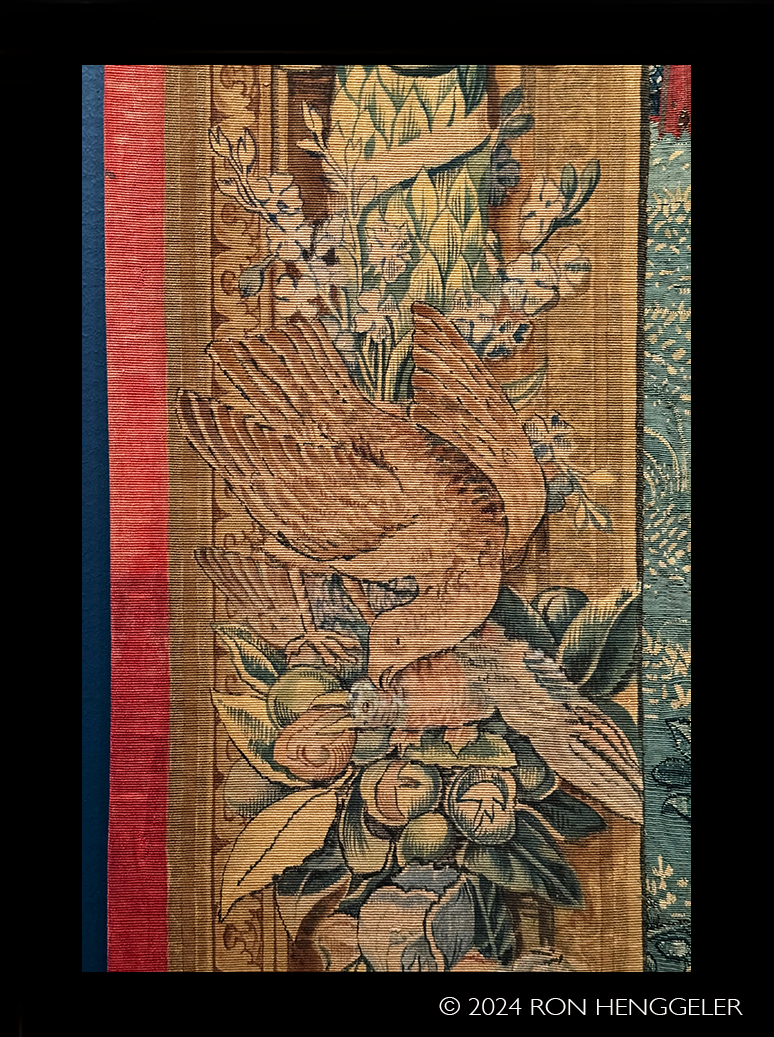

Border detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

Detail of: Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with

|

||

|

||

Border detail of: The Flight of the French Rear Guard under the Duke of Alençon, ca. 1528-1531 |

||

|

||

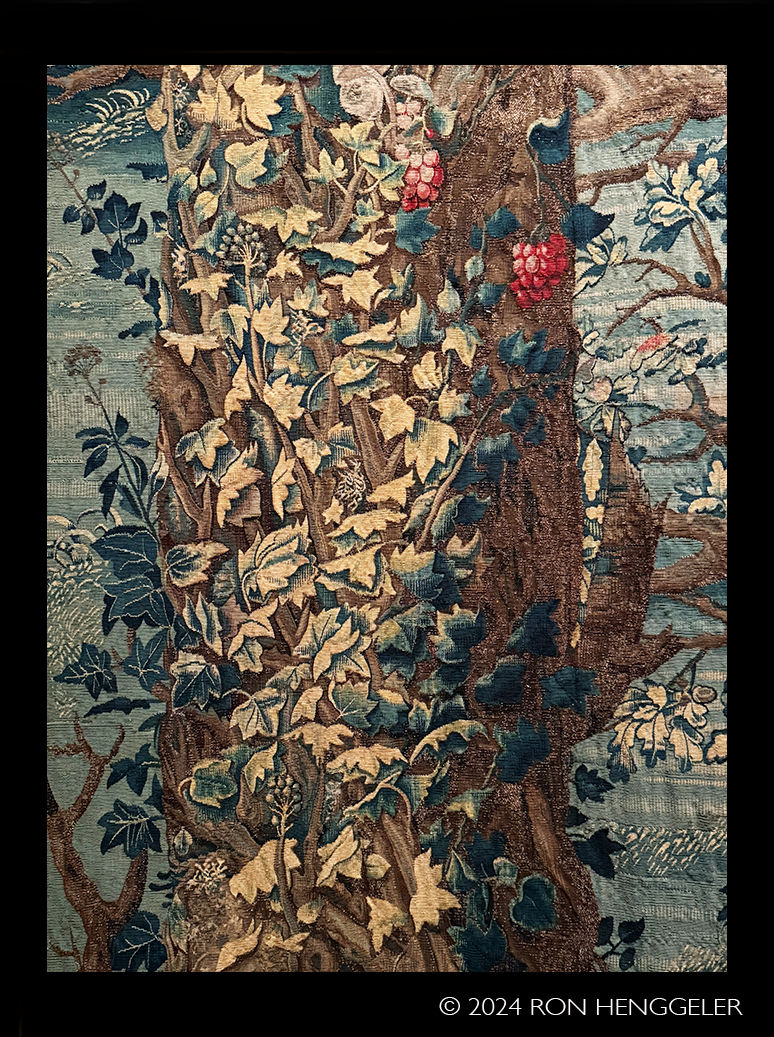

All seven tapestries were originally framed by rich borders. The top and side borders were decorated with garlands of flowers, fruits, birds, and animals; the bottom border featured aquatic motifs. The borders were later removed from the tapestries, but by the time they were bequeathed to the Museo di Capodimonte, the borders of three of the tapestries-including this one—had been restored on the top and sides with floral borders from the original series. The borders on the other four tapestries are painted on fabric to resemble the originals. On the right border of this tapestry is Willem and Jan Dermoyen's weavers' mark. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

In this panoramic view of the battlefield, the Swiss infantry, fighting for the French, lay down their arms and abandon the battle. As troops of Swiss mercenaries signal their surrender, Swiss captain Johann von Diesbach valiantly offers up his life to an imperial knight to uphold his honor by dying on the battlefield. From the left, the imperial baggage train —the civilians who traveled with the army, including family members, porters, cooks, merchants, engineers, surgeons, clergy, and others - makes its way from their encampment through a breach in the wall to the park occupied by the French. As the defeat of the French troops becomes evident, they rush to the field to claim the spoils of war. |

||

|

||

|

||

At the bottom left, in the foreground of the tapestry, a churlish mercenary soldier accompanied by a young boy, perhaps his son or a page, catches our eye as he bounds forward with some chickens hanging from his pike—a common trope of plunder. Behind him, a friar and a few richly attired women enter the battlefield, while a chained monkey climbs above his cage, which has been loaded on the back of a horse. In this scene, tapestry designer Bernard van Orley created numerous picturesque details of the imperial baggage train, or camp followers, many of whom would hurry to pick over the battlefield for loot upon the French troops' defeat. The weavers expertly capture the varied facial expressions of the motley entourage and vivid details like the multicolored chicken feathers. |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

Detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

Border detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

|

||

Border detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

In the upper right side of the tapestry, a crucial event unfolds. Identifiable by the white crosses on their doublets and jerkins, the Swiss mercenaries, who make up the bulk of the French infantry, abandon their formations, not hearing the pleas of their officers. The Swiss pikemen have been cut off by the sudden imperial cavalry charge. |

||

|

||

In the upper left corner of the tapestry, the double-headed Habsburg eagle on one of the tents indicates the location of the imperial camp. The civilian camp followers and some imperial soldiers, identified by red saltire (X-shaped) crosses, have begun to move through the defenses and breaches in the wall enclosing the French camp. Loaded with baskets and chests, they prepare to plunder the battlefield. |

||

|

||

In the foreground, the figure in light blue clothing wielding an immense pike that reaches from top to bottom of the tapestry is the valiant Swiss captain |

||

|

||

Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with |

||

|

||

|

||

Border detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: The Incursion of the Imperial Baggage |

||

|

||

The Battle of Pavia Tapestries at the de Young |

||

|

||

"Medallion" armor garniture,

|

||

|

||

At center foreground, an agitated group of soldiers represents the defeated French troops. To the left a soldier rests his hand on the blade of an immense two-handed sword in the ground that served as a gathering spot for troops during the battle. Discarded weapons at their feet, a cowering drummer and fifer seem to sink under the weight of their heavy chains bedecked with fleurs-de-lis and a red rampant animal. A standard-bearer next to them allows the French flag to fall to the ground, signaling the imminent defeat of the French forces. |

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Detail of: Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with |

||

|

||

Attributed to

|

||

|

||

D'Avalos armor helmet, ca. 1550

|

||

|

||

Detail of: Brescia knight on horseback in tournament armor with

|

||

Newsletters Index: 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006

Photography Index | Graphics Index | History Index

Home | Gallery | About Me | Links | Contact

© 2023 All rights reserved

The images oon this site are not in the public domain. They are the sole property of the

artist and may not be reproduced on the Internet, sold, altered, enhanced,

modified by artificial, digital or computer imaging or in any other form

without the express written permission of the artist. Non-watermarked copies of photographs on this site can be purchased by contacting Ron.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)