| |

November 2, 2024

Tamara de Lempicka

The Queen of Art Deco at the de Young Museum |

|

| |

|

|

| |

With paintings exuding stylized modernity and sapphic sensuality, Tamara de Lempicka (Polish, 1894-1980) helped define the Art Deco aesthetic and proliferate its global diffusion in the 1920s and 1930s. |

|

|

|

| |

Her powerful nudes and androgynous portraits of male and female lovers and patrons challenged gender norms and encapsulated the glamour, transgression, and cosmopolitan effervescence of the Parisian années folles, the roaring years between the wars. Blending the compositional complexity of sixteenth-century Italian Mannerism and the deftness of line of nineteenth-century French Neoclassicism with the dynamism of the Russian and European avant-gardes, Lempicka's style was singular: "Among a hundred paintings, you could always recognize mine." She enjoyed critical and commercial success in the 1920s, but as the taste for figurative art declined, the artist was all but forgotten. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Born Tamara Rosa Hurwitz to a Polish family of Jewish descent, she mostly grew up in Saint Petersburg, where she met her first husband, Tadeusz Lempicki, from whom she took the feminine declension Lempicka-altered to the more noble and francophone "de Lempicka." Following the October Revolution (1917), they fled to Paris, where she signed early works under the masculinized "Lempitzky." Capturing with her art the vitality of the resurging city and creating a public image as flawless as the glossy surfaces of her paintings, Lempicka became the toast of the town. She left Europe for the United States just before the start of World War |I (1939-1945), settling for a time in California with her second husband, Baron Raoul Kuffner. The artist, now Baroness Kuffner, became a favorite of Hollywood celebrities. Yet her work fell out of favor until the 1970s, when the ever-resilient Lempicka was rediscovered as a leading figure of Art Deco. Today, she stands out as one of the most receptive, gifted, and technically accomplished painters of her generation.

Tamara de Lempicka's place of birth remains uncertain, and she became a citizen of the United States in 1945. However, Lempicka identified as Polish and made statements to this effect throughout her life. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

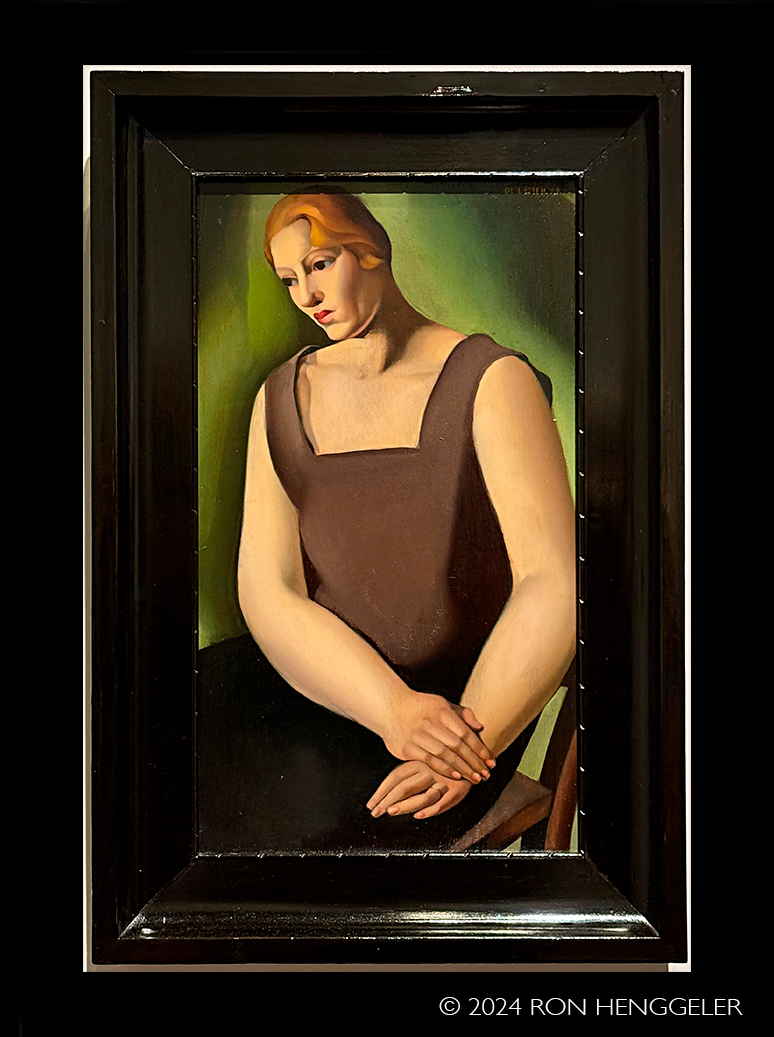

The Bohemian Woman

(La bohémienne), ca. 1923

Oil on canvas

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

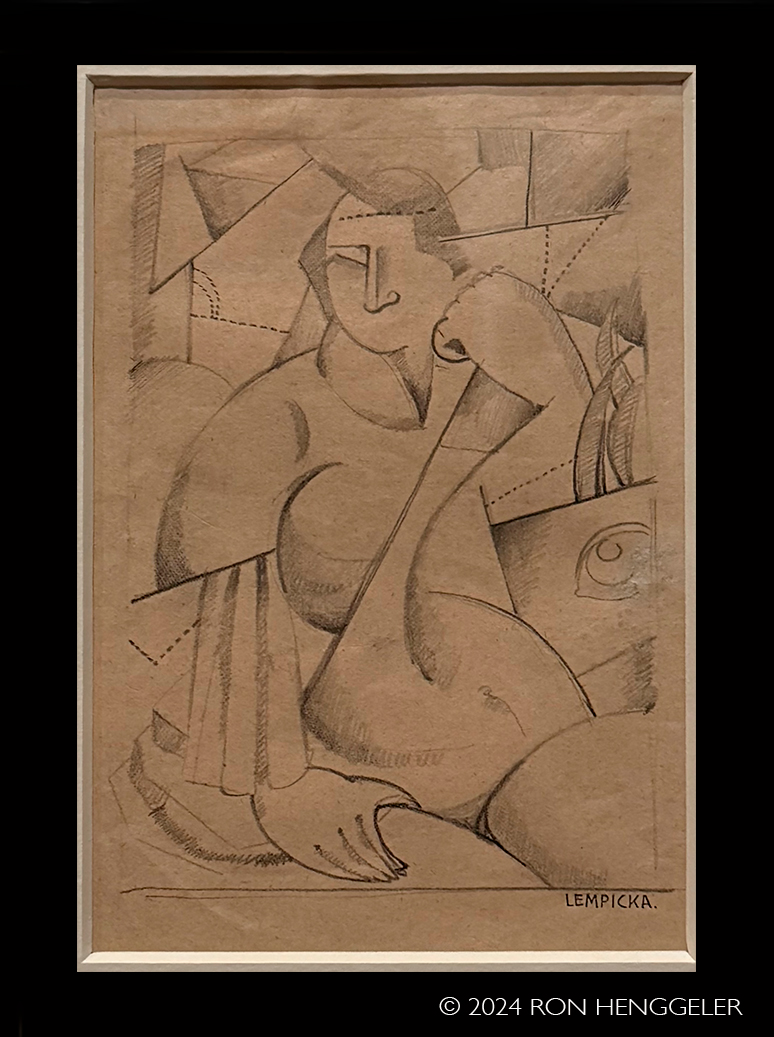

Cubist Woman Seated, 1922

Graphite

Collection of Henryk Bury |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

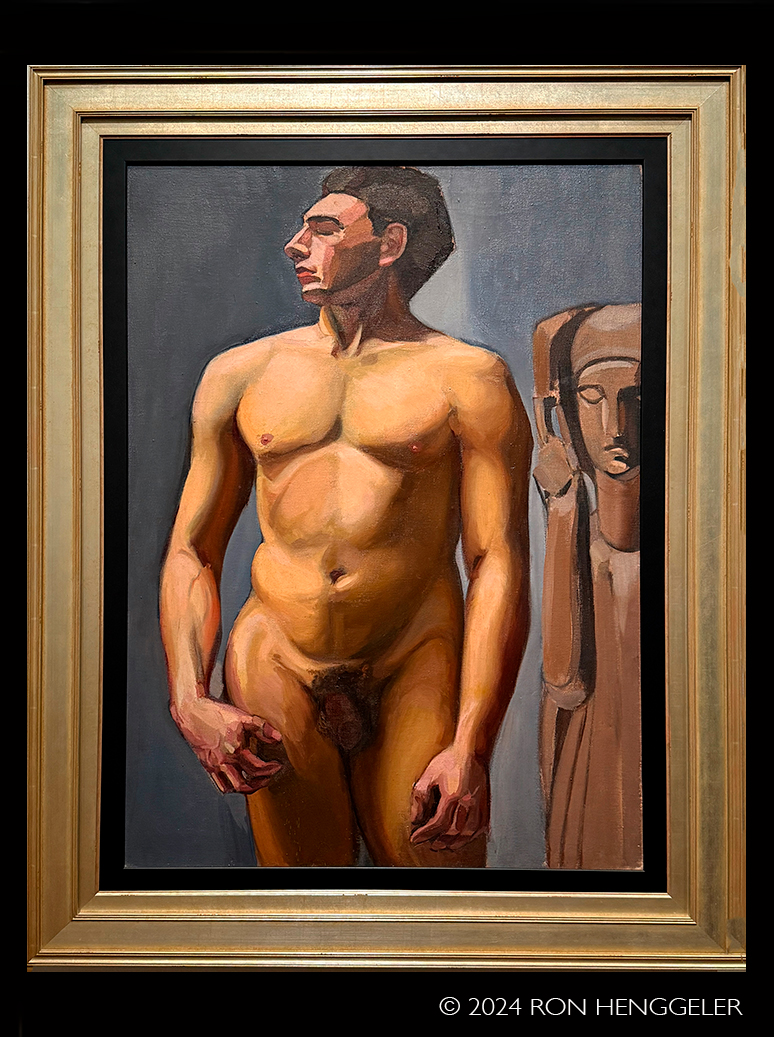

Male Nude, ca. 1924

Oil on canvas

Collection of Harvey Fierstein |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

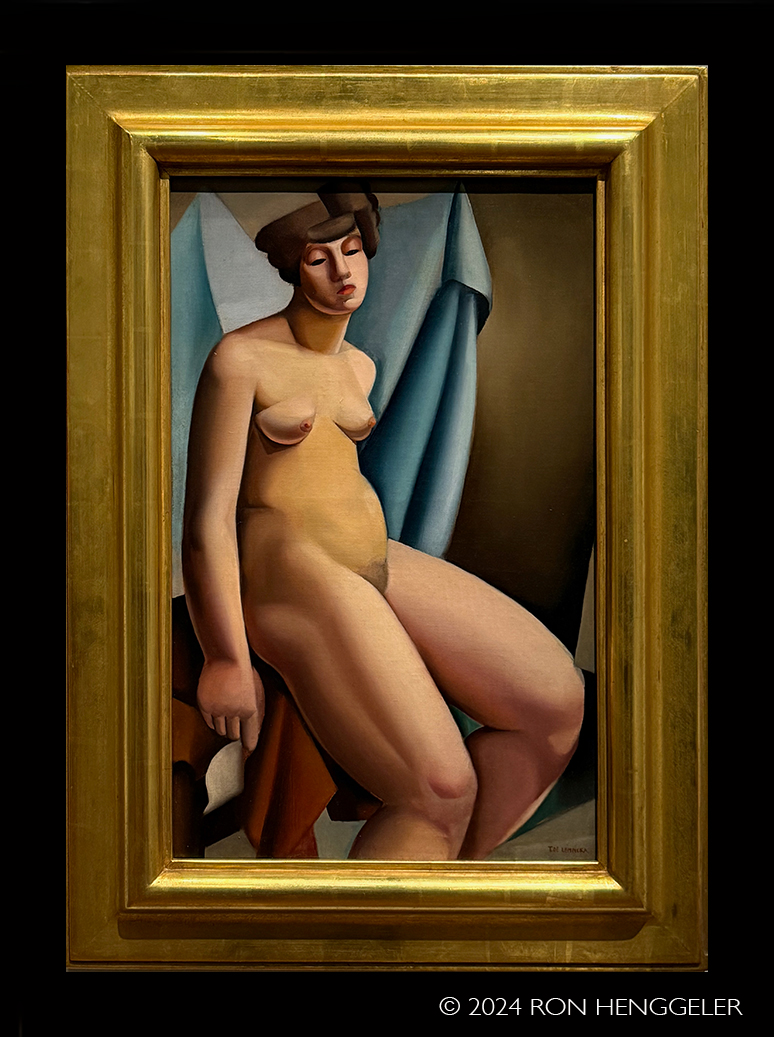

Seated Nude, ca. 1920-1925

Oil on canvas

Private collection, Los Angeles |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

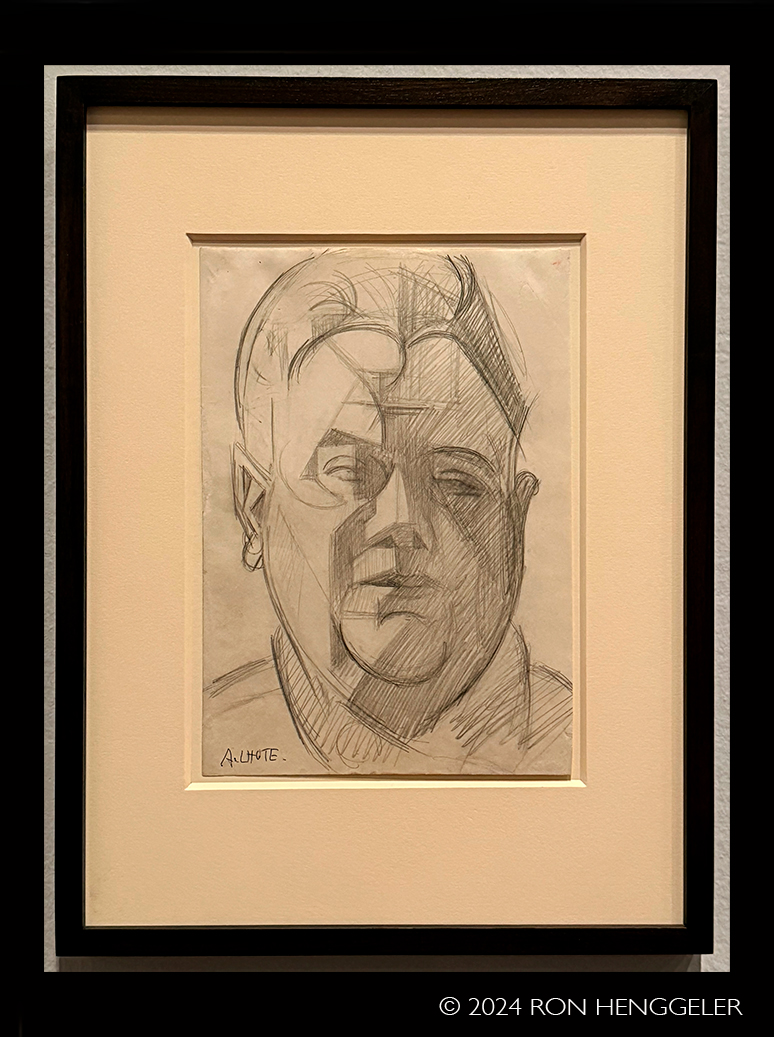

André Lhote (French, 1885-1962)

Portrait of Camille Renaud, 1920-1944

Graphite on wove paper

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund, 1986.2.10 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Pink Background

(Portrait of Bibi Zogbé), 1923

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Known as Bibi, Labibé Zogbé (1890-1973) was a Lebanese painter active in Paris who modeled for some of Tamara de Lempicka's earliest works, including Russian Dancer (on view nearby). This study of Zogbé's face is among the first documented paintings by Lempicka, who presented it at her first solo exhibition, in Milan, in 1925. It reflects the deep influence of André Lhote, particularly in its similar treatment of a figure through fragmented planes that reduce the form to basic geometric shapes, apparent in Lhote's Portrait of Camille Renaud (on view nearby). |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

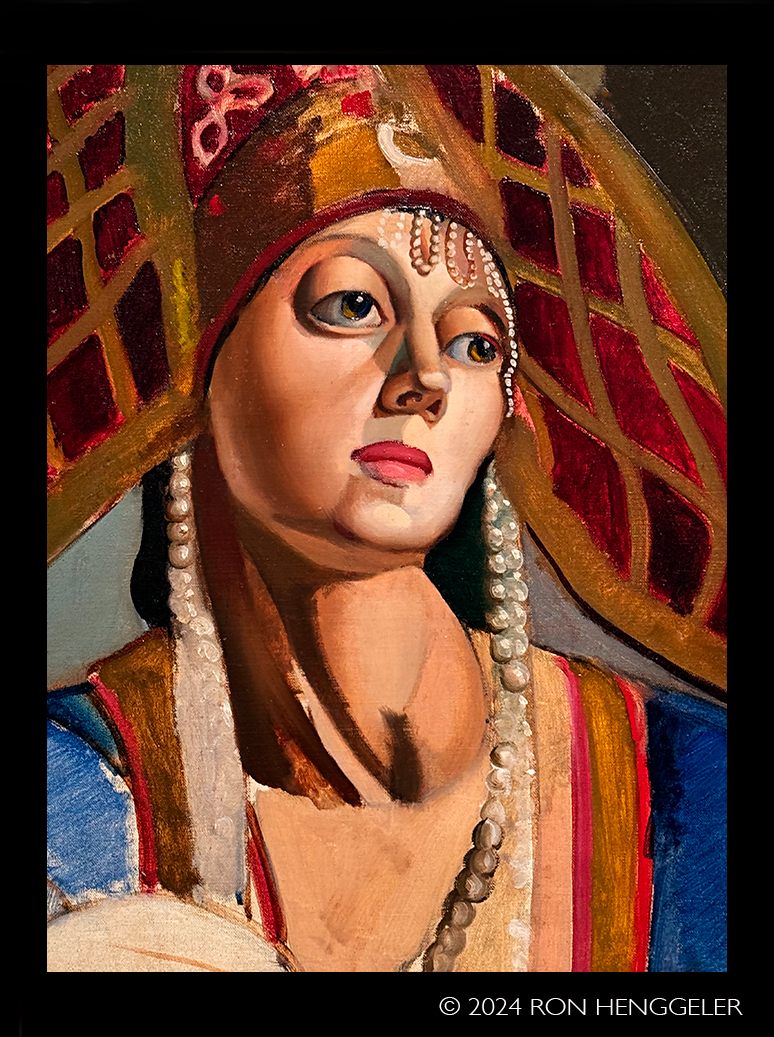

Russian Dancer, 1924-1925

Oil on canvas

Collection of Marek Roefler/ Villa la Fleur, Konstancin-Jeziorna, Poland

This painting, posthumously titled in reference to the Ballets Russes-the troupe founded by Serge Diaghilev, which took Paris by storm in the 1910s and 1920s with its innovative choreography and gleaming costumes and sets designed by Russian artists-portrays a woman dressed in folk attire from southern Russia. The model, possibly Tamara de Lempicka's friend, Lebanese artist Bibi Zogbé, wears traditional garments that may have been owned by Lempicka, including a stunning kokoshnik (headdress) richly decorated with pearls. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Russian Dancer, 1924-1925

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Still Life with Russian Doll (Hyacinth), ca. 1924

Oil on canvas on cardboard

Private collection

Closely bound to the community of Russian émigrés in Paris, Tamara de Lempicka painted a series of works from 1924 through 1926 containing references to the land she abandoned after the October Revolution. In this humble still life, the artist inserts a note of nostalgia with the blue doll, a typical Russian toy carved from wood. The small, handcrafted object became a lucrative business for Russian artists in Paris at the time, like Natalia Goncharova and Alexandre Benois. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Still Life with Cauliflower, ca. 1924-1925

Oil on canvas

Collection of Roy and Jenny Niederhoffer |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Bouquet of Violets, ca. 1927

Oil on board

Collection of Henryk Bury |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

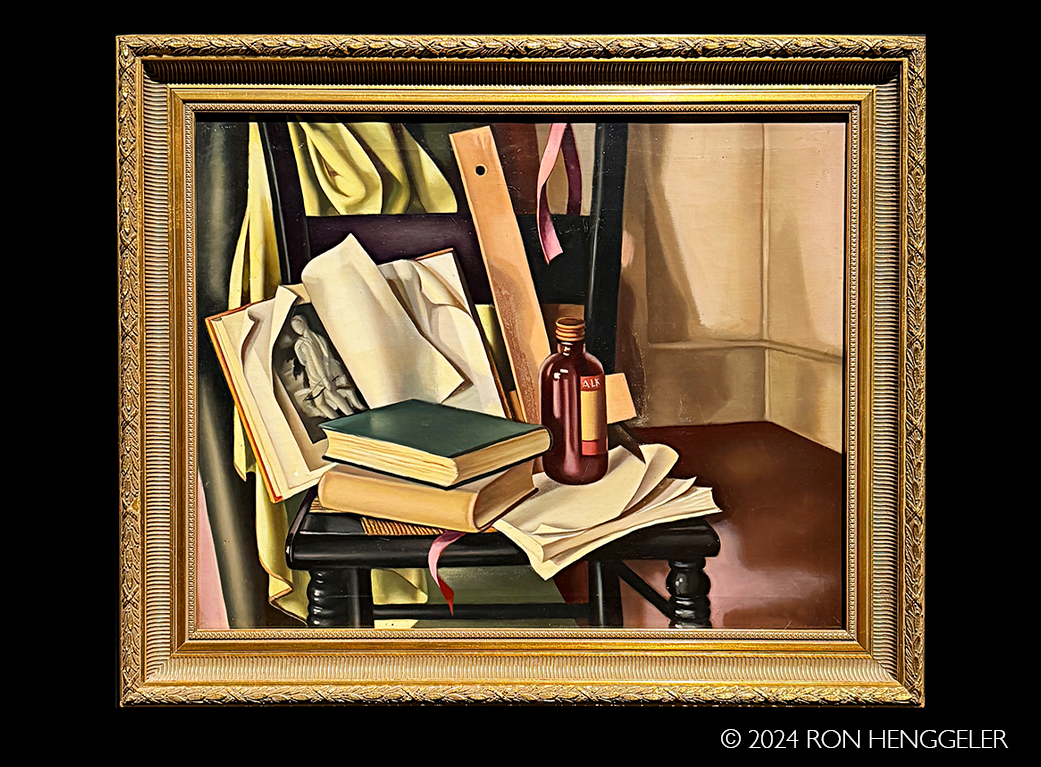

Studio Corner, ca. 1924

Oil on canvas

Collection of Marek Roefler

Villa la Fleur, Konstancin-Jeziorna, Poland

This interior scene records some clues as to the artist's early, struggling years in Paris. Located in a garret, possibly her residence at 1, place de Wagram, or 5, rue Guy de Maupassant, the space contains a small bookshelf and a storage chest. It might also depict a corner of André Lhote's art academy in Mont-parnasse. The composition plays on shades of blue, which blend gradually with the gray of the wall. The painting suggests the artist's years of study-including drawing practice and reading manuals-and an artistic quest still taking place within the walls of the home. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Weariness (Lassitude), 1927

Oil on oak panel

Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, Warsaw |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Study for The Round Dance (La ronde), after Madonna of the Long Neck (1534-1535) by Parmigianino, ca. 1932

Graphite

Museo Soumaya.Fundación Carlos Slim, Mexico City, 52422 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Kizette on the Balcony, 1927

Oil on canvas

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne / Centre de création

industrielle, Paris, Gift of the artist, 1976, inv. AM 1976-1133

Among the first paintings that garnered Tamara de Lempicka critical recognition is this portrait of Kizette.

The young girl fills the entire picture plane, occupying a liminal space between the domestic world (symbol-izing her infancy) and the metropolis seen at distance (symbolizing adulthood). The critical success of the painting encouraged Lempicka to use her daughter as a model often in the following years. Since the artist did not wish to be recognized publicly as a mother, upon this painting's presentation a few months later at the Salon d'Automne in Paris, it was simply titled

Au balcon (On the Balcony). |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

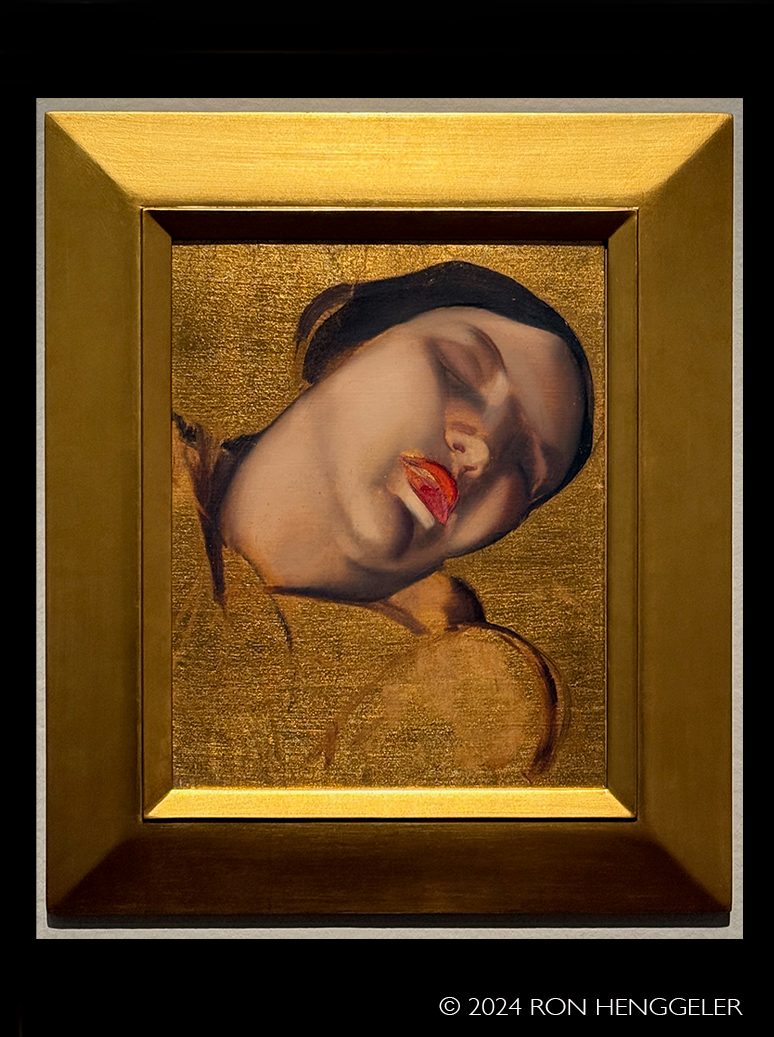

Saint Teresa of Avila,

after The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1652) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1930

Oil on panel

Museo Soumaya. Fundación Carlos Slim, Mexico City, 50558

Saint Teresa of Avila is a painterly transposition of Gian Lorenzo Bernini's masterpiece of Roman baroque sculpture. Possibly working from a photograph, Tamara de Lempicka added fleshier tones to Bernini's icy white marble while retaining his purity of form and the ecstatic expression of the visionary saint. The veil, inflected in varying tones of gray, emphatically foregrounds the living flesh, the meaty, pink lips half-open in a sigh of abandon. The painting documents just how frequently and continuously the artist studied and played off the European Old Masters throughout her career. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Green Veil, ca. 1924

Oil on canvas

Palais Princier, Monaco

An early example of the spiritual tension in Tamara de Lempicka's production, this painting appears to be a Virgin Mary in an emerald-colored veil, a transgressive depiction since it departs from the traditional blue. The figure seems inspired by a Neoclassical source, Italianartist Francesco Hayez's Odalisque, which Lempicka may have seen in Milan ahead of her solo exhibition in 1925. The artist shrinks the frame, borrows the posture as well as the hairstyle and part, and, in changing the color of the veil, transforms the subject into a modern Madonna-wearing lipstick and with made-up eyes looking heavenward. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Portrait of Prince Eristoff, 1925

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Prince Aleksandr Konstantinovich Eristoff arrived in Milan in 1920 and belonged to a noble Georgian family whose members immigrated to Northern Italy and France after the October Revolution. He owned by inheritance the rights to the production of Eristoff vodka, passed on by his son to Count Rossi of the Martini & Rossi firm. In Tamara de Lempicka's painting, the aristocratic sitter is portrayed against an urban view that could be a detail of Milan's navigli (canals). It was first presented at Lempicka's first solo exhibition, in Milan, in 1925, and is signed

"de Lempitzki," a masculine declension of her surname. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

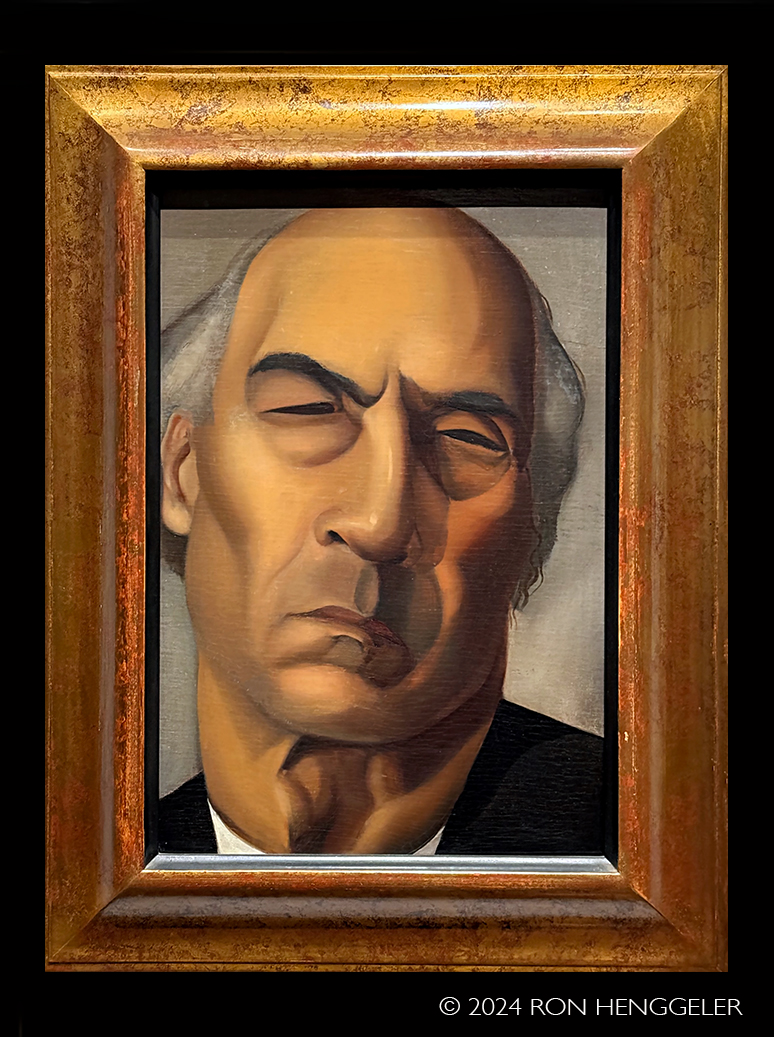

Portrait of Baron Raoul Kuffner,

1928-1932

Oil on panel

Centre Pompidou Musée national dart moderne /Centre de création industrielle. Paris. Gift of the artist. 1976

inv. AM 1976-911

Baron Raoul Kuffner (1886-1961) began collecting Tamara de Lempicka's works in 1928 and, following her divorce from Tadeusz Lempicki, became her second husband, in 1934. His aristocratic title was acquired by his father, Karl, and their main property was the castle ofDiöszegh, in today's Hungary. This sharply defined closeup of the baron dates to the couple's early encounters. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

MONSIEUR LEMPITZKY

In the early 1920s, when Tamara de Lempicka first exhibited at the Parisian salons-juried exhibitions where artworks were presented and sold to the public-she signed her works using the masculine declension of her surname, "Lempitzky" (with slight variation), willfully blurring her gender identity. While the salons had always been open to men and women, the juries, critics, and buyers who could ensure an artist's success were predominantly men.

Lempicka also introduced gender-fluid imagery into her portraits.

Women are characterized by a vigor and assertive coolness, while men are accorded a sexual charge and captured with languid attitudes and in affected poses rarely seen in the genre. Her sitters included members of the Parisian intelligentsia, the Milanese jet set, and "White Russians"-exiled aristocrats who, like Lempicka, had left their privileged world behind following the October Revolution (1917). She portrayed them all as clear-cut, angular figures, using extreme, and flattering, proportional distortions.

Lempicka held her first solo exhibition in 1925, the same year as the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, which prompted the mainstreaming of the Art Deco aesthetic. Her gallery of modern aristocracy codified her distinctive and enormously successful format of portraiture: rooted in French Neoclassicism, smoothly executed, and impossibly stylish. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

KIZETTE DE LEMPICKA:

A MODEL DAUGHTER

Marie-Christine "Kizette" de Lempicka (1916-2001) was born in Saint Petersburg, a few months after Tamara married Tadeusz. The family enjoyed a brief period of high-society amusement before leaving for Paris in the aftermath of the October Revolution (1917).

Young Kizette served as a model for her mother, appearing in most of the artist's earliest paintings— receiving her First Communion, reading prayers in a Polish babushka, as a teenager in tennis attire-which garnered Lempicka her first critical recognition. Kizette was also, however, a cumbersome presence to Lempicka, hampering the artist's professional aspirations and desire for an independent lifestyle; she often introduced Kizette as her little sister.

Despite ups and downs in their relationship, Kizette remained a constant and caring presence in her mother's life. We owe to her the survival of most of Lempicka's graphic and painted oeuvre, as well as the first biography ever written on the artist, Passion by Design: The Art and Times of Tamara de Lempicka (1987). |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

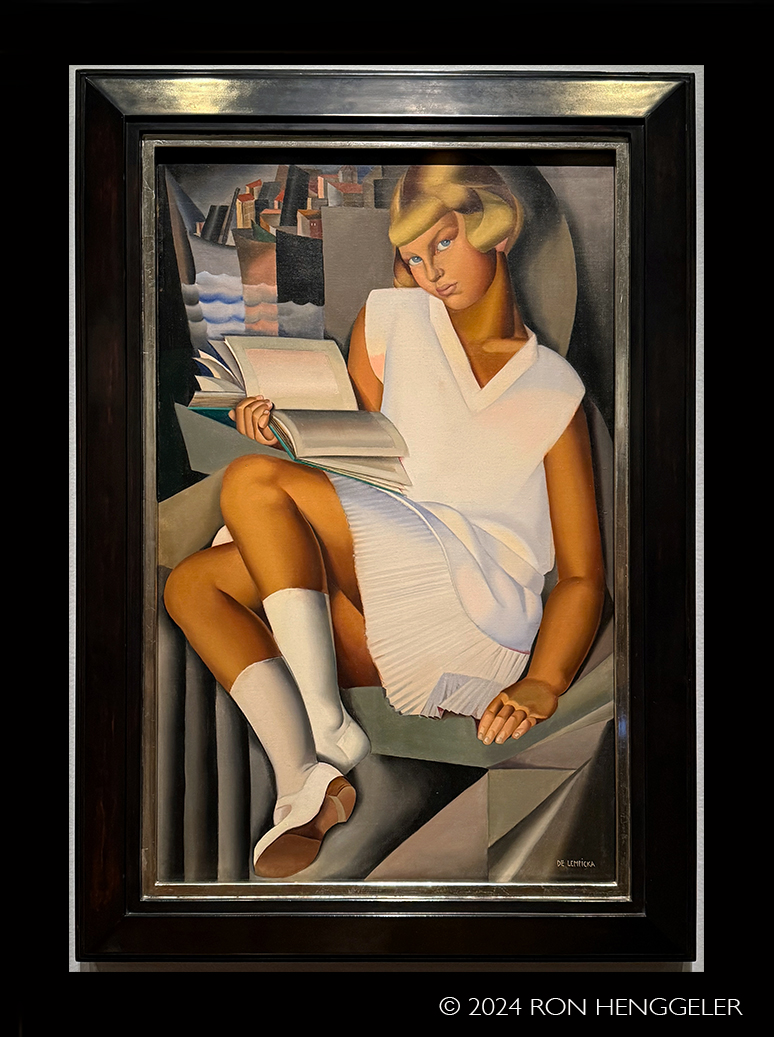

Young Girl in Pink (Kizette in Pink Il), ca. 1928—1929

Oil on canvas

Collection of Patty and Jay Baker, courtesy of Artis-Naples, The Baker Museum, Naples, Florida

Built around various inflections of pink and gray enlivened by puffs of blue in a background of silhouetted ships, this painting features Kizette wearing a fashionable tennis outfit. Tamara de Lempicka produced this canvas after the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes in France (now the Musée d'arts de Nantes) acquired the first version, which enjoyed critical success, in 1928. Lempicka brought this second version with her when she traveled to the United States in 1929; it arrived in San Francisco, where it ended up in the collection of Boris Kitchin, an entrepreneur living in nearby Hillsborough. In 1930 it was presented at an exhibition organized by art dealer Beatrice Judd Ryan at San Francisco's Galerie Beaux Arts.

Kizette de Lempicka, ca. 1922. Courtesy of the Tamara de Lempicka Estate |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

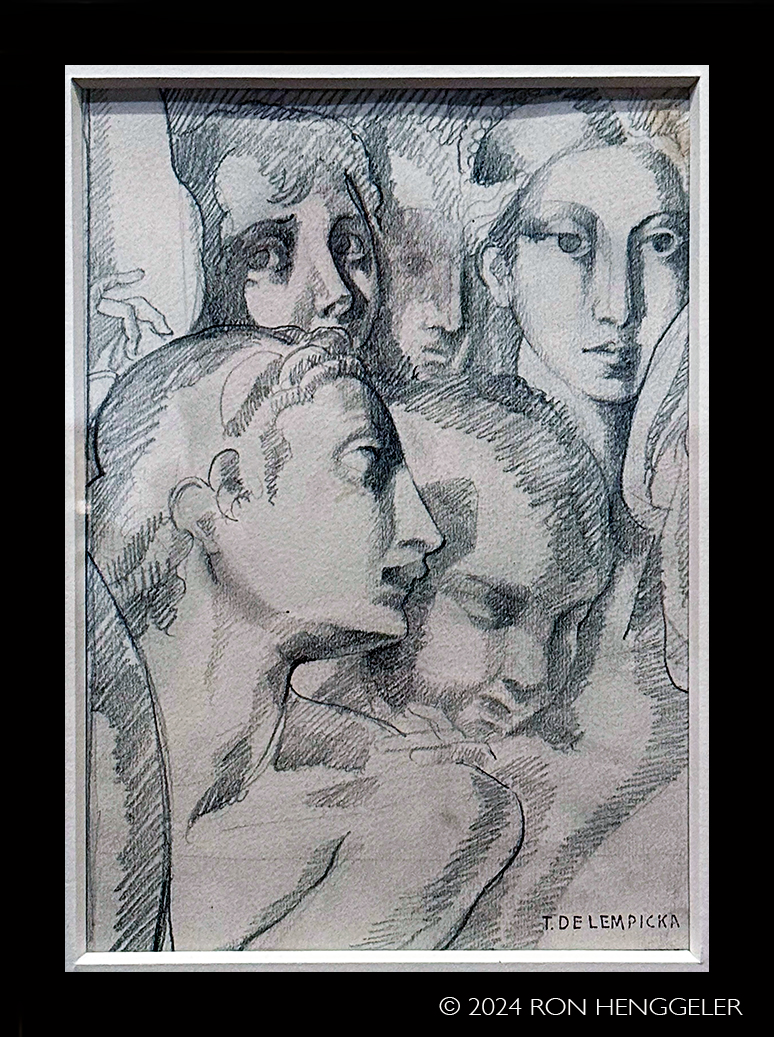

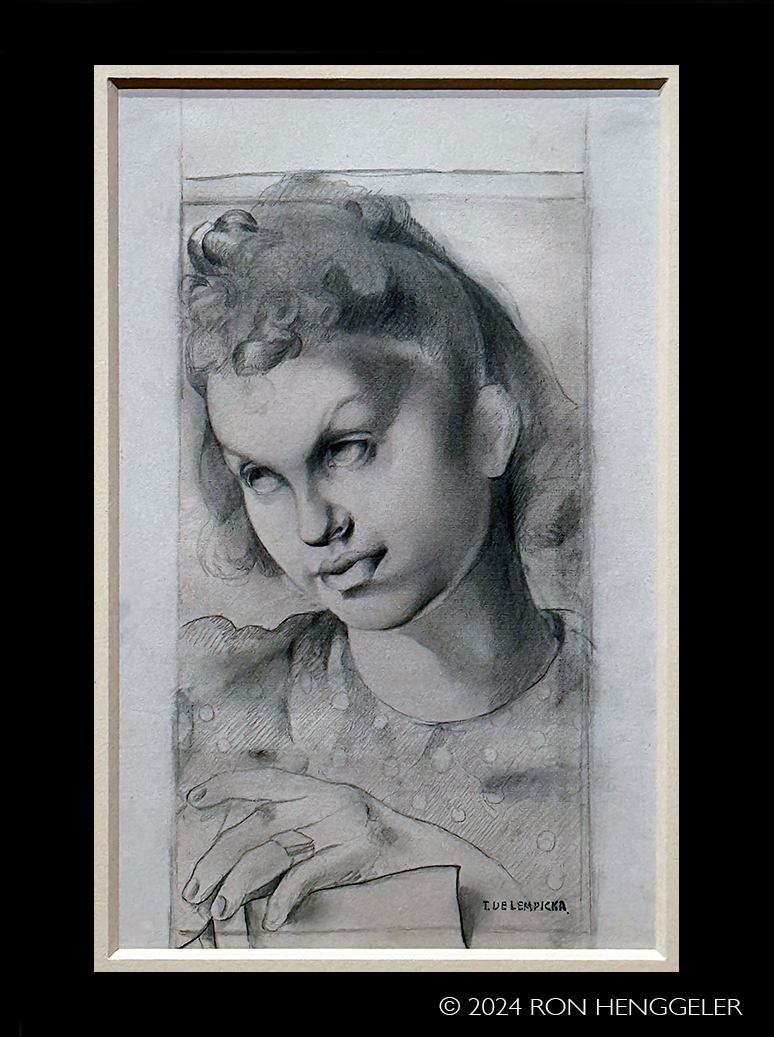

Study for Young Girl Drawing, ca. 1937

Graphite on Fabriano paper

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Lisa Sardegna and David Carrillo, Phoebe Cowles and Robert Girard, and Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts Endowment Fund, 2022.10

Precisely drawn in a silvery graphite, this captivating portrait study of Kizette features strong modeling, a technique that anticipates Tamara de Lempicka's painting style. Wearing a polka-dot blouse while holding a sketchbook, Kizette is rendered with a slightly sinister expression. The highly finished nature of this drawing and the presence of framing lines surrounding the figure-perhaps indicating the panel's intended cropping-suggest it was likely made at a late stage in the design process for a never-completed painting. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Communicant, 1928

Oil on canvas

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne / Centre de création industrielle, Paris, Gift of the artist, 1976, on deposit to La Piscine-Musée d'art et d'industrie André Diligent de Roubaix, France, inv. AM 1976-1134, D994.4.34

The Communicant demonstrates great compositional skill and chromatic finesse: the drapery is sumptuous, its volume constructed by means of the lively folds of the veil, and the painting is a tour de force in its complex play with shades of white and gray. Featuring a stagy spiritual Kizette receiving the First Communion, this portrait was perhaps meant to disguise the family's Jewish heritage in the face of rising anti-Semitism in the years leading up to the Holocaust. Kizette herself could never recall having taken the Communion. First exhibited at the 1928 Salon d'Automne, Paris, The Communicant was later presented at Poland's Powszechna Wystawa Krajowa, Poznan, organized in 1929 to celebrate the decennial of Polish independence, where it won a bronze medal. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Portrait of His Imperial Highness Grand Duke Gavriil Konstantinovich, ca. 1926

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Gavriil Konstantinovich (1887-1955) was a high-ranking officer in the hussars of the Russian Imperial Guard and belonged to the Romanov family, which ruled Russia from 1613 until the February Revolution overthrew the imperial government in 1917. In 1918 Konstantinovich was arrested by the Cheka, the Soviet secret police, along with a number of his relatives, who were then shot. Sick with tuberculosis, he was freed thanks to the intervention of writer Maksim Gor'ky.

Gavriil and his wife, Anastasia, fled to a sanatorium in Finland before finally landing in Paris. This is the story behind the tormented face portrayed here by Tamara de Lempicka, a countenance marked by the pallor of illness, the pride of lost rank, the melancholy of exile, and homesickness. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

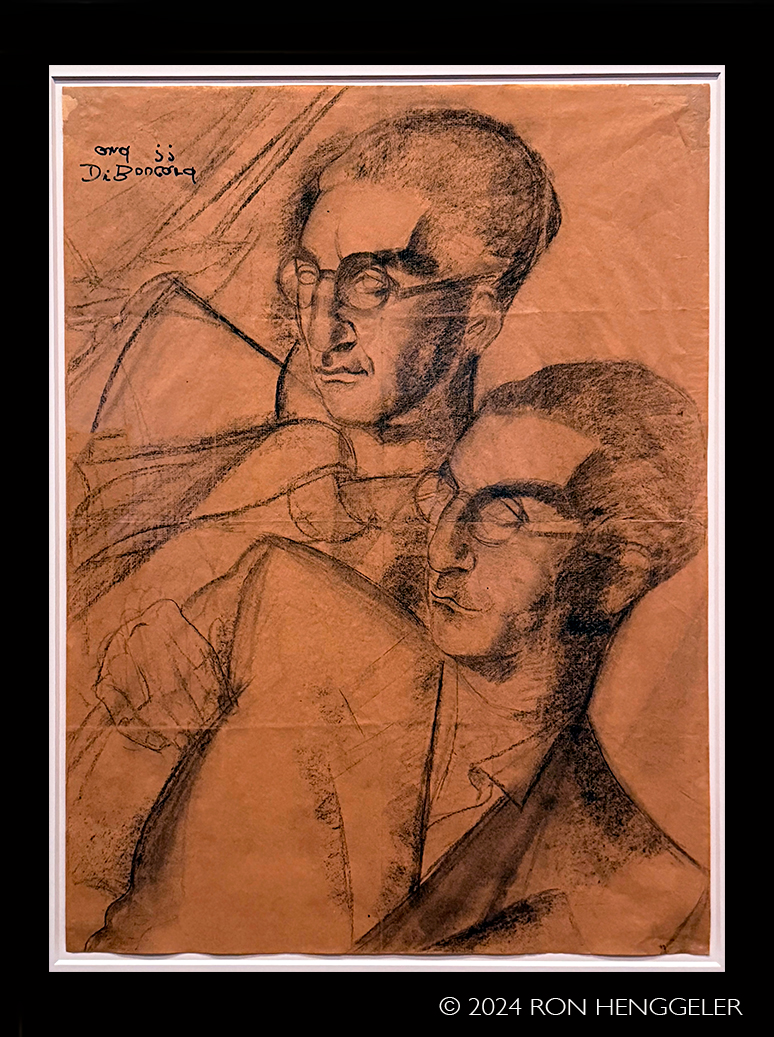

Double Portrait of Jan and Joël Martel,

ca. 1931

Charcoal

Collection of Henryk Bury |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Polish Girl

(Kizette with a Polish Shawl), 1933

Oil on panel

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Portrait of André Gide, 1925

Oil on cardboard

Private collection

Praised by critics of the time for its chilling appearance, this portrait of French author André Gide (1869-1951), who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1947, dates to the same year that his groundbreaking novel Les Faux-monnayeurs (The Counterfeiters) (1925), which shocked readers with its honest treatment of homosexuality, was published. Tamara de Lempicka here expresses facets of Gide's complex personhood-dominated by a conflict between his Protestant upbringing and his gay identity— by applying an aesthetic of distortion and fragmentation derived from Futurist and Cubist works. Gide was a jury member at the 1923 Salon d'Automne, at which Lempicka exhibited, and played an important role in promoting the artist's early career in Parisian intellectual circles. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Two Young Girls with Ribbons, 1925

Oil on canvas

Collection of Dr. George and Vivian Dean |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Her Sadness, 1923

Oil on canvas

Private collection, courtesy of Sotheby's

In this early work, still signed with the masculine declension "Lempitzky," Tamara de Lempicka captures her lover Ira Perrot wearing a slightly oversized coat, frowning, and with a penetrating gaze, a portrait daunting in its nearly life-size scale. A photograph of it was published in 1924 in the French magazine Arlequin and accompanied by a poem written by Perrot under her pseudonym, Ira Verte.

Titled "L'idole" ("The Idol"), the poem is an ode to an unnamed object of adoration, likely Lempicka: "White, black, gray is their kingdom of stone / their reign is the reign of hard minerals / their soul colder than cold stone / the icy gaze of their opal eyes." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

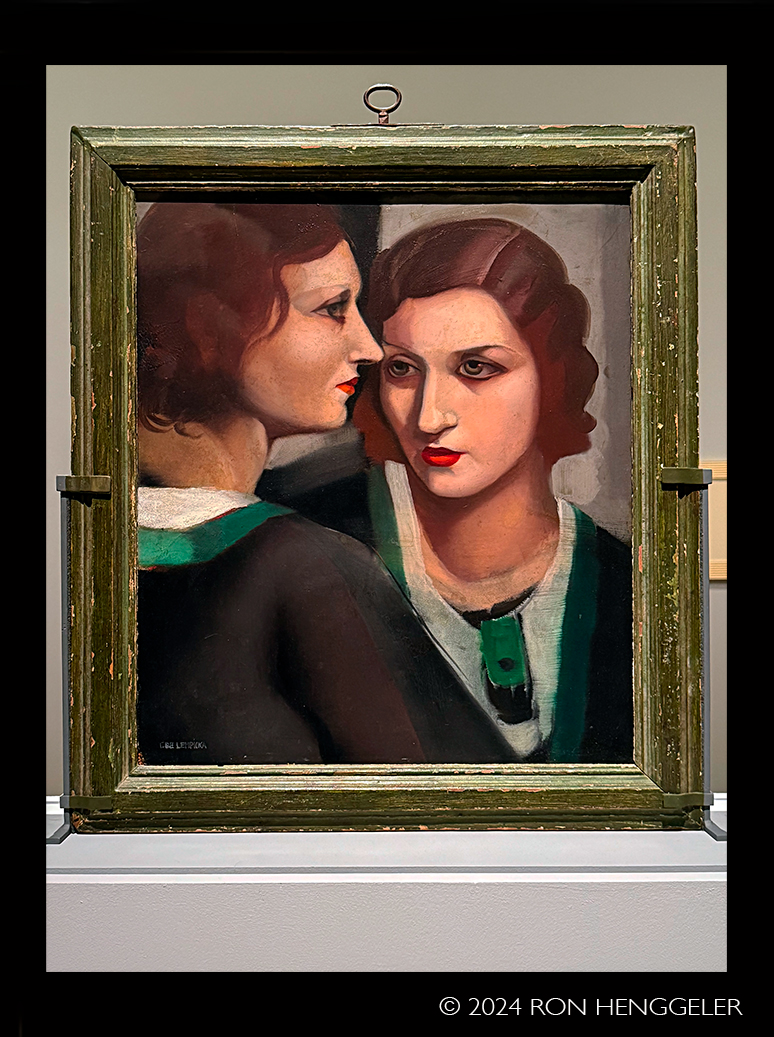

Face and Profile (Double Portrait) (recto), 1931;

Sketch for a Double Portrait (verso), ca. 1925

Oil on panel (recto); oil over graphite on panel (verso)

The Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch Collection, Berlin |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Mother and Child, 1931

Oil on plywood panel

MUDO-Musée de l'Oise, Beauvais, France, inv. 76.252 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Portrait of Ira P., 1931

Oil on panel

Private collection

This painting stands out as one of Tamara de Lempicka's most powerful homages to lifelong love and muse Ira Perrot. Holding a bouquet of calla lilies in a quasi-nuptial dress, Perrot is wearing a high-fashion creation similar to the "Conte blanc," a formfitting evening gown made of peau d'ange satin by Maison Blanche Lebouvier, featured in the fashion magazine L'Officiel in September 1931. Lempicka's seductive painting cannily combines modern style and spirit with more traditional references, such as the diagonal compositional format and the cool, detached gaze typical of Italian Mannerist portraiture. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

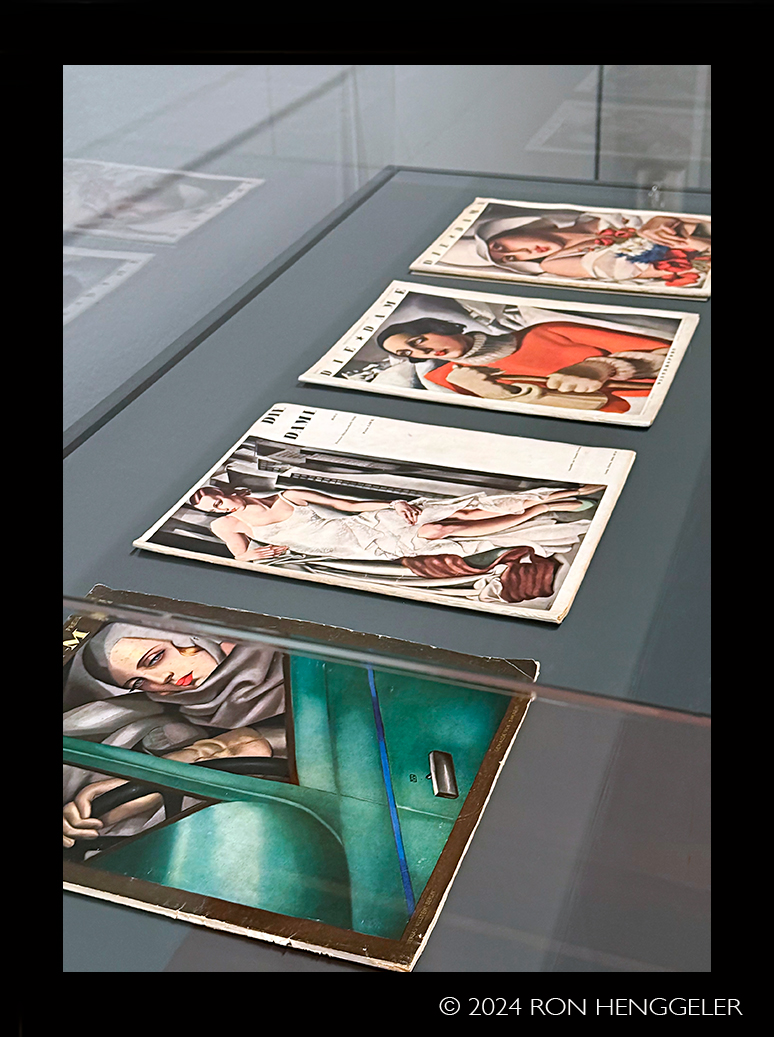

TAMARA DE

LEMPICKA

By 1930 Tamara de Lempicka had cemented her cool, high-gloss pictorial style. Her female portraits, in particular, reflected the optimism of an era when women began enjoying greater social and economic access and agency. Capable of fashioning her own personality and path through stylish modes of dress, Lempicka was the embodiment of "the modern woman" as described by Vogue magazine in May 1929.

Fashion also played an important part in Lempicka's career.

She started as a fashion illustrator in the early 1920s and continued to design covers for popular women's magazines, like Germany's Die Dame (The Lady). In her paintings, she vividly captured the plurality of styles available to women in this era. Like the convention-defying women who wore them, these garments represented a radical departure from preceding periods, with the modest and physically constrictive designs of earlier decades giving way to sinuous and draped silhouettes that emphasized women's shapes while also allowing greater liberty of movement. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Brilliance (Bacchante), ca. 1932

Oil on panel

Collection of Rowland Weinstein,

courtesy of Weinstein Gallery, San Francisco |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Straw Hat, 1930

Oil on panel

Collection of Professor Mark Kaufman, Monaco |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Irène and Her Sister, 1925

Oil on canvas

Private collection, courtesy of Irena Hochman Fine Art Ltd., New York

Captured in a towering double portrait, sisters Irène (1902-1994) and Romana Ludmila Dekler (1904-1984) were Tamara de Lempicka's cousins. Like Lempicka, the two sisters fled Russia after the October Revolution to Paris, arriving in 1921. They are portrayed in urban day wear, and their appearance is defined by geometric, nearly mechanical shapes, which contrast with the natural background against which they are set. The portrait was featured in 1927 in Vanity Fair. According to Lempicka's ambitious claim, per her daughter's biography of her, this was the painting that started the Art Deco movement. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Saint-Moritz, 1929

Oil on panel

Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans, France, Gift of the artist, 1976, inv. 76.12.1

In 1928 the Swiss resort town of Saint Moritz hosted the Winter Olympics. With women making their way into the world of competitive sports, the German magazine Die Dame celebrated the event by featuring this painting on its winter cover (on view nearby).

Saint Moritz had become a meeting place for European high society and Hollywood, having been the refuge of choice for movie stars Charlie Chaplin and Gloria Swanson. The model in this painting, wearing a sweater by French fashion designer Jean Patou, can be identified as Ira Perrot, the poet with whom the artist had an enduring romantic relationship. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Young Woman in Green

(Young Woman with Gloves), ca. 1931

Oil on board

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d'art moderne / Centre de création

industrielle, Paris, Acquired by the State, 1932, inv. JP 557 P

An emblematic image of Art Deco, Young Woman in Green encapsulates the optimism of the interwar period by paying tribute to the era's dynamic "modern woman." The figure here is rendered through the aes-thetic of the machine, her anatomy reduced to smooth geometric forms. Her conical breasts, curved hips, and deep navel are swathed in a green fabric that breaks up into folds and flutters, becoming a kind of second skin. As she shades her eyes with the edge of a wide-brimmed hat, this woman looks beyond the frame and into the future, expressing a sense of feminine freedom and hopefulness propagated by the fashions of the time. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Arums, 1931

Oil on panel

Peterson Family Collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Woman with a Green Glove, 1928

Oil on panel

Private collection

Both the slanted posture of the sitter and the malachite-green details of her ensemble infuse a nearly electric dynamism into this unfinished portrait of an unidentified woman, coiffed à la garçonne, an androgynous style fashionable at the time. Tamara de Lempicka's emphasis on the figure's assertive pose, as she rests on a classical pedestal, and her use of fashion to express the sitter's power and social status are elements that the artist reprised from the sixteenth-century Italian Mannerist portraiture of Agnolo Bronzino, Parmigianino, and Jacopo Pontormo, whose paintings she admired for their sophistication and style. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

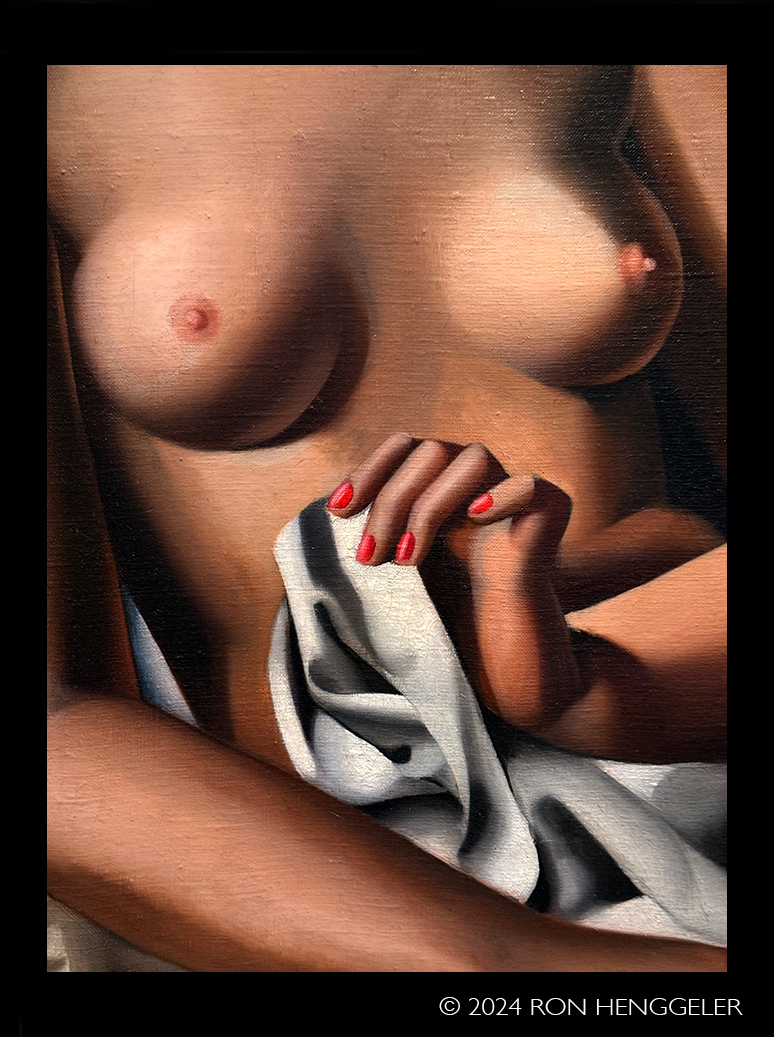

Nude with Buildings (Nu aux buildings), 1930

Oil on canvas

Collection of Caroline Hirsch

Exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris in 1931, this half-covered nude emerges in near-sculptural relief from the crisp folds of white drapery. With her cool gaze, the woman looks polished to perfection and carefully made up, with her eyebrows drawn in a line and hair styled in the carved curls then in fashion. Her warmly hued body, the olive branch held between her fingers, and the pink of her lips and fingernails stand out in contrast to the cold, metallic tones of the skyscrapers, a visual motif that Tamara de Lempicka began to incorporate into her compositions following her trip to New York in 1929. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Portrait of Mrs. Rufus Bush, 1929

Oil on canvas

Collection of Patty and Jay Baker, courtesy of Artis-Naples, The Baker Museum, Naples, Florida

Commissioned to paint a portrait of Joan Price Jeffery (1910-2003), niece of Thomas B. Jeffery, the producer of the first Rambler automobiles, to commemorate her impending marriage to Rufus Bush, son of industrialist Irving T. Bush, Tamara de Lempicka arrived in New York in 1929. The artist took Joan to Hattie Carnegie, a leading US fashion designer, and chose clothes for the sitter: a bright red coatdress that allows a glimpse of a black skirt and translucent silk stockings underneath. The narrow canvas barely contains Joan, strong-willed and androgynous with her short hair, standing in front of a sleek background of New York skyscrapers. Three preliminary drawings (on view nearby) attest to Lempicka's accuracy in the preparation of the painting and also indicate she was planning for a portrait of Rufus Bush, never completed. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

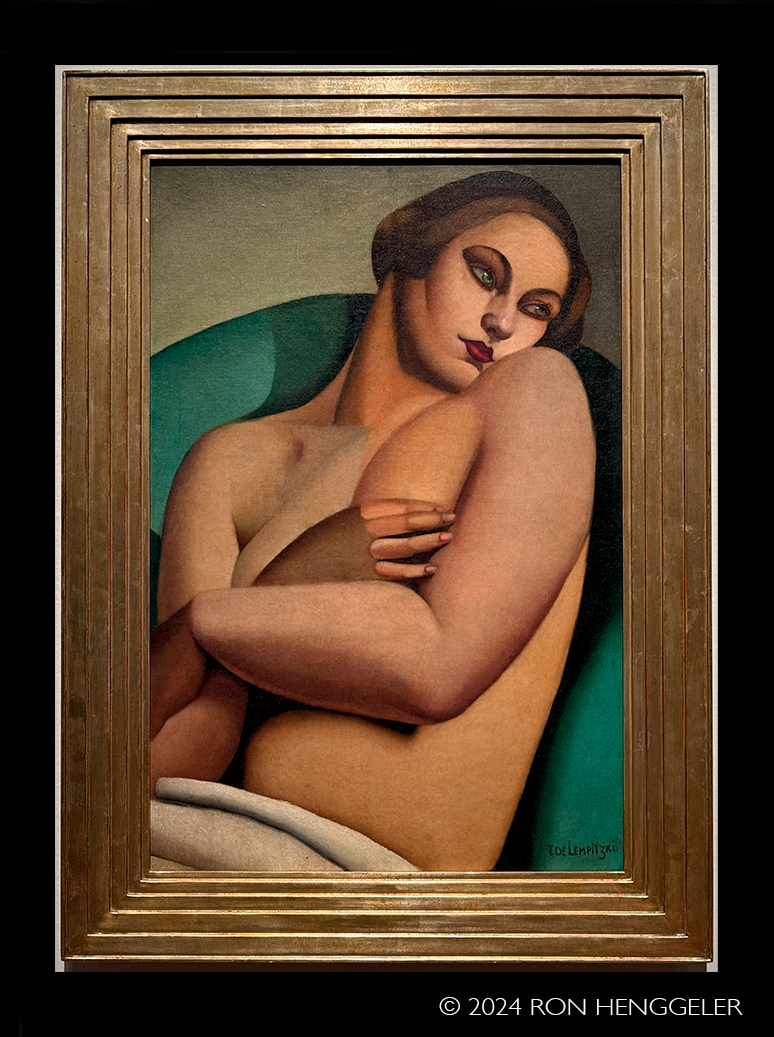

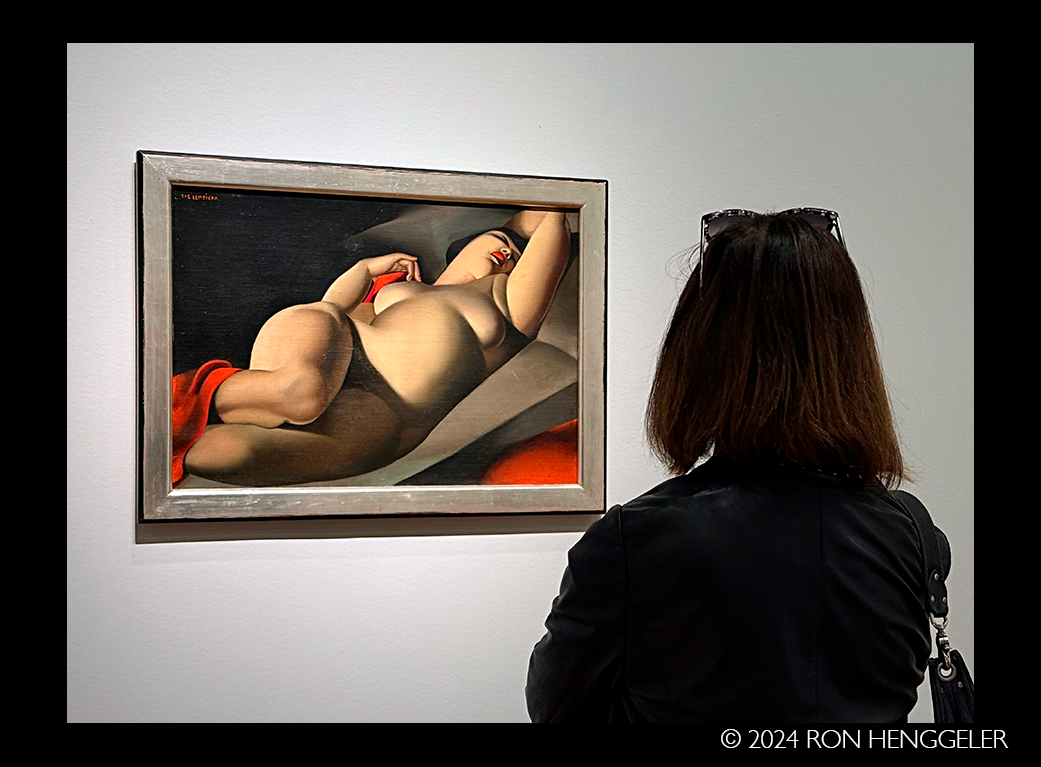

THE SAPPHIC NUDES:

TRADITION AND TRANSGRESSION

The female nude was traditionally considered the male painter's domain and its object the gratification of the heterosexual male gaze. Tamara de Lempicka recognized it as the principal genre through which she could find acknowledgment within the patriarchal codes of the academic salons and garner admiration from critics, the public, and a more liberal clientele.

Aesthetically innovative, Lempicka's nudes are characterized by an unabashed portrayal of female sexuality. They reveal her predilection for realistic bodies represented through elementary forms, devoid of detail, following contemporary neoclassical and purist trends. The artist also reworked canonical themes through her choice of all-female subjects and their treatment; she avoided portraying women as idealized odalisques, bathers, or heroines from Greek mythology or the Old Testament— as was the convention per her male predecessors, such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Pierre-Auguste Renoir-instead choosing contemporary subjects and setting them against modern, metropolitan backgrounds.

By prominently featuring women's bodies as dominant and attentive to their own erotic pleasure, she showed their sexual power.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

La belle Rafaëla in Green, ca. 1927

Oil on canvas

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Figure Study on a Gold Background, ca. 1930

Oil on gold leaf on cardboard Collection of Andreas Fallscheer, Switzerland |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

La belle Rafaëla, 1927

Oil on canvas

Collection of Tim Rice

One of Tamara de Lempicka's most remarkable compo-sitions, this intimate painting depicts a nude woman absorbed in her own erotic plea-sure. Together with

La belle Rafaëla in Green and the related oil sketch, Figure Study on a Gold Background (both on view nearby), it is a tribute to the titular Rafaëla, a sex worker the artist met in the Bois de Boulogne park in Paris and one of her lovers. A rich texture of art historical references characterizes this memorable image. While its cool voluptuousness draws from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres's Neoclassical portrayal of exotic odalisques, the distinctively sensual pose, captured from a low angle, is also traceable to Gustave Courbet's Bacchante. The dramatic lighting and rigorous color palette-limited to black, gray, and the red of Rafaëla's lips and shawl-is an homage to Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Leaning Nude I, 1925

Oil on canvas

Private collection, Europe

Inspired by the chaste sensuality and purity of lines beloved by Neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, this elegantly contorted nude epitomizes the classically rooted yet modern style for which Tamara de Lempicka became renowned. In a

departure from Ingres, Lempicka's nude does not portray an idealized or mythological figure but a contemporary woman, captured in a moment of intimacy. In 1925, when Lempicka first presented this painting, it was rare for a female artist to paint such explicit pictures, and Lempicka signed it "T. de Lempitzki," using a masculine declension of her surname. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Woman with Dove, 1931

Oil on panel

Collection of Patty and Jay Baker, courtesy of Artis-Naples, The Baker Museum, Naples, Florida

This is an example of Tamara de Lempicka's visions amoureuses (visions of love), which feature close-ups of women in scenes that often provocatively combine sentimentalism with sexuality, as epitomized in this painting. Lempickaexplores the tension of the blond, blue-eyed nude clutching a dove, a symbol of love and purity (as the messenger for Greek goddess Aphrodite), looking upward longingly. Placing a stronger emphasis on the erotic element, Lempicka based this figure on an eighteenth-century pastel by Venetian artist Rosalba Carriera, whose oeuvre, like Lempicka's, focused almost exclusively on portraiture and allegorical images of young women. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Spring, 1930

Oil on panel

Private collection

The pristine pictorial finish of this composition-which looks almost enameled-is tempered by its erotic character, featuring two nude women, possibly Tamara de Lempicka and Ira Perrot, filling the tight picture plane with their embrace and a lush bouquet of white lilacs. With The Girls (on view nearby), of a similarly sapphic nature, Spring was presented in 1930 at Lempicka's first solo exhibition in Paris, at the Galerie Colette Weil. There it was noticed by the critic André Warnod who, in his review, wrote, "Her art is not cold despite its precision. Her portraits are alive and even hallucinatory. Sometimes it seems as if her painted characters are about to step out of the frame." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

The Girls, 1930

Oil on panel

Collection of Patty and Jay Baker, courtesy of Artis-Naples, The Baker Museum, Naples, Florida |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Tamara de Lempicka, with fox fur, jewels, and cigarette, 1938

Photographic print Studio Joffé

(Constantin Joffé, Russian, 1910-1992)Tamara de Lempicka Estate

BARONESS KUFFNER

In 1939, under the impending threat of Nazi invasion, Tamara de Lempicka and her second husband, Raoul Kuffner, a Hungarian baron and also of Jewish descent, left Europe for the United States.

She became an emigre once again. Taking up residence in Los Angeles and New York, and ultimately joining her daughter, Kizette in Houston, she plotted her artistic comeback by reintroducing herself as the Baroness Kuffner.

She made savy use of the American press, which nicknamed her the "baroness with a brush." Once the painter of modern cosmopolitan life, in the United States Lempicka presented herself as the herald of the grand European pictorial tradition, producing religious paintings and humble still lifes inspired by the Flemish Old Masters Lempicka's parents converted from Judaism to Christianity before she was born, and she designed a Christian identity through her images. In the lead up to and during World War II (1939-1945), her shift in subject matter from glamorous portraits to religious scenes perhaps bespeaks an underlying fear for herself and her family given their Jewish heritage.

She presented her latest works in a series of solo exhibitions, including one in San Francisco in 1941, but the mixed reviews led to her progressive withdrawal from artistic life. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

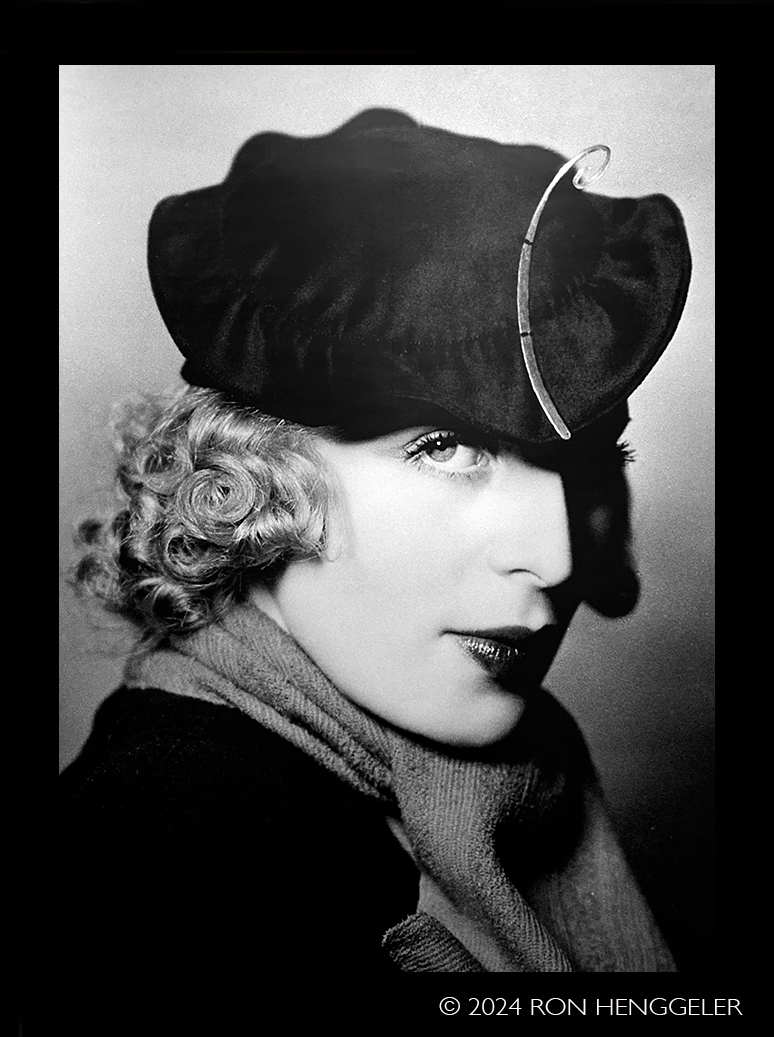

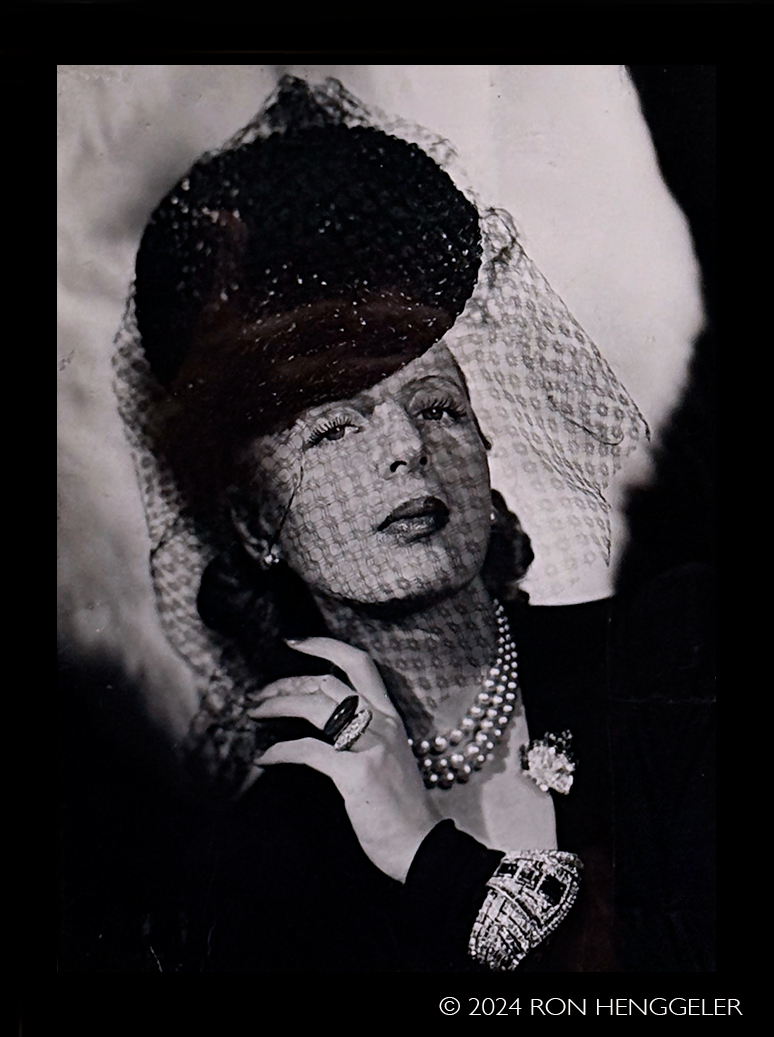

Tamara de Lempicka with veil, ca. 1938

Photographic print Studio Joffé

(Constantin Joffé, Russian, 1910-1992) Tamara de Lempicka Estate

SAN FRANCISCO, 1941:

THE BARONESS IN THE CITY

"Baron and Baroness de Kuffner will arrive today at the Palace Hotel," announced the San Francisco Examiner on September 13, 1941, ahead of Tamara de Lempicka's exhibition at the Courvoisier Galleries (formerly on 133 Geary Street). Organized by New York-based art dealer Julien Levy and entirely sponsored by Baron Kuffner, the exhibition featured the artist's neobaroque and religious works.

While Lempicka's flawless pictorial technique received praise at the time, the sentimental pauperism and overly religious nature of her subjects was deemed insincere and passé by local press. The mild critical reception the artist received was counterbalanced by the social excitement with which she was welcomed by local high society, including Helen de Young Cameron-the daughter of the de Young Museum's founder,

M. H. de Young, and wife of George T. Cameron, then publisher of the San Francisco Chronicle-who threw cocktail and dinner parties in honor of the mysterious baroness.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

At the Opera, 1941

Oil on canvas

Private collection

At the Opera was described as

"masterly" by the San Francisco Call-Bulletin and Tamara de

Lempicka's technique "flawless" by the San Francisco Examiner when it was presented in San Francisco in 1941. The setting is a theater box with baroque decorations, and Lempicka's rendering of the various fabrics(the plush velvet, the transparent voile, the glossy satin) provides a splendid example of the artist's technical virtuosity. Patently artificial and walking the line between Mannerism and kitsch, the painting was a personal favorite of Andy Warhol's, who lost a bidding war for the canvas in 1980 to German fashion designer Wolfgang Joop, one of Lempicka's most passionate collectors. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

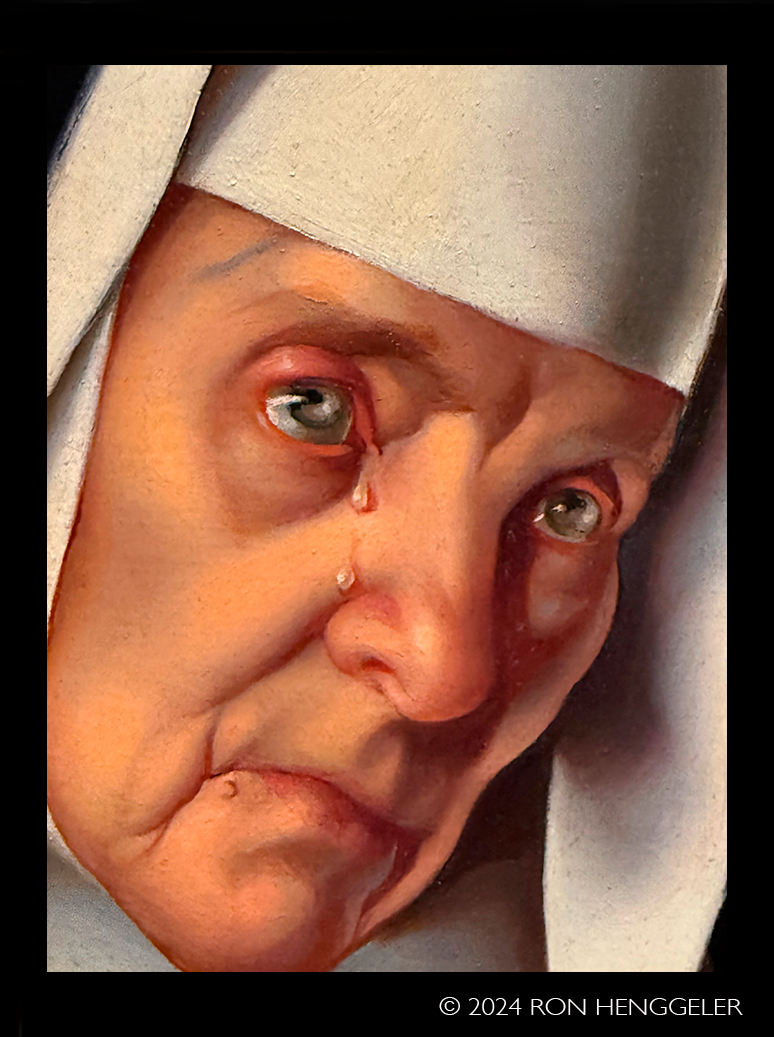

The Mother Superior, 1935-1939

Oil on canvas laid down on board Musée d'arts de Nantes, France, inv. 976.7.1.P

During a period of depression in 1935, Tamara de Lempicka made her way to a convent near Parma, Italy, where she met a Mother Superior who managed to restore

a sense of serenity in her. The artist chose this painting for the press campaign announcing her 1941 exhibitions in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Perhaps the sentimental character of this weeping nun led critics to consider the art of "the baroness" in a negative light; the painting demonstrates her exceptional technical skills, but the San Francisco Call-Bulletin criticized its artificiality, epitomized by The Mother Superior's fake "glycerine tears." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Madonna (Round Madonna), ca. 1937

Oil on panel

MUDO-Musée de l'Oise, Beauvais, France, inv. 76.254

Realized in the classic format of Florentine Renaissance devotional paintings, the tondo (circular painting), this Madonna was first presented in Paris in 1938, as part of an exhibition organized by the Société des Femmes Artistes Modernes. In addition to exhibiting the work of contemporary women artists, the group also promoted a return to more classical subjects and traditional national values, like maternity. When Tamara de Lempicka presented the painting in her solo exhibitions in San Francisco and Los Angeles in 1941, the press praised this "wistful Madonna" for its exquisite and painstaking pictorial technique.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Saint John the Baptist, 1936

Oil on board

Muzeum Narodowe w Lublinie, Lublin, Poland |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Graziella, ca. 1937

Oil on panel

Musée d'art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre, France, D.79.1

Tamara de Lempicka presented this idealized, Botticelli-inspired painting at her solo exhibition in San Francisco in 1941. Ahead of the opening, Lempicka sat for an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, fashion-ing herself as an indefatigable working artist in high demand, waking up at 6 a.m. and work-

ing for fourteen hours a day: "It is hard to combine my social activities [...]. I live for my painting. I have no children. My pictures are my children." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Peasant with a Pitcher, ca. 1937

Oil on panel

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

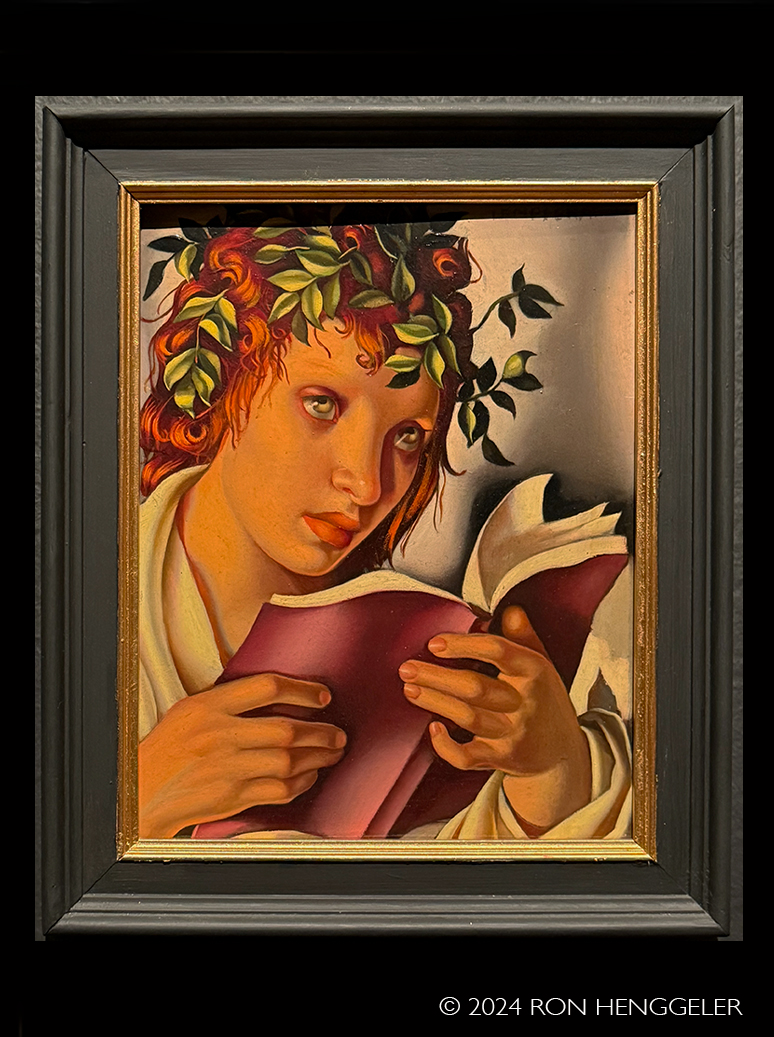

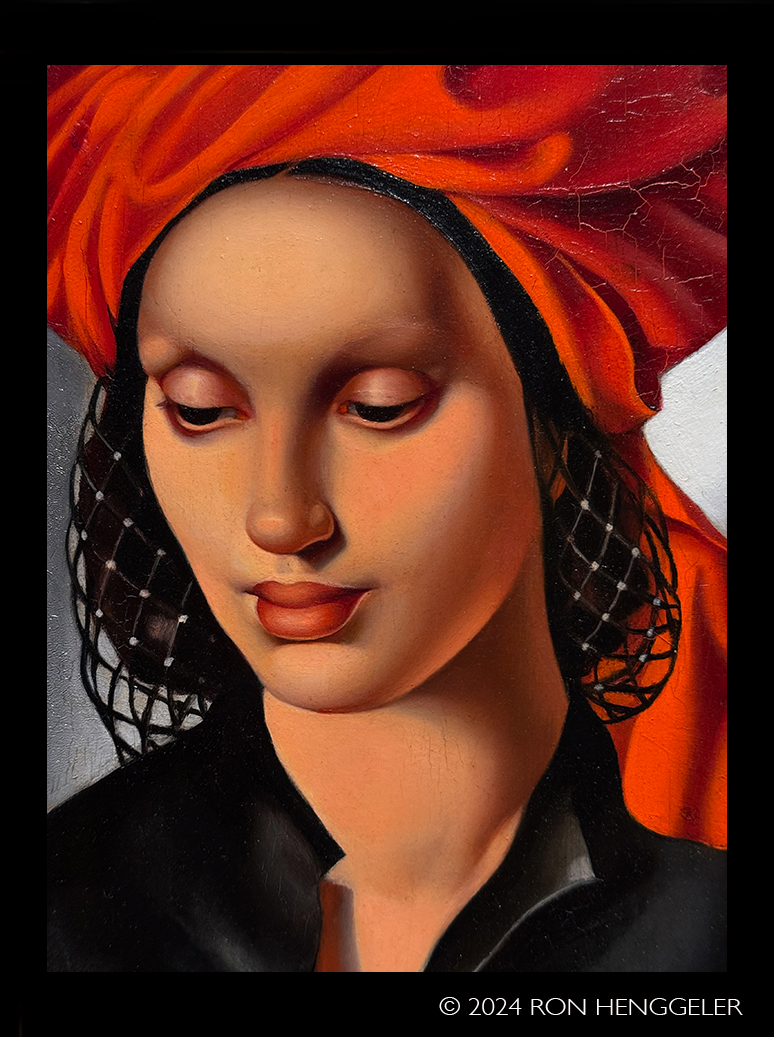

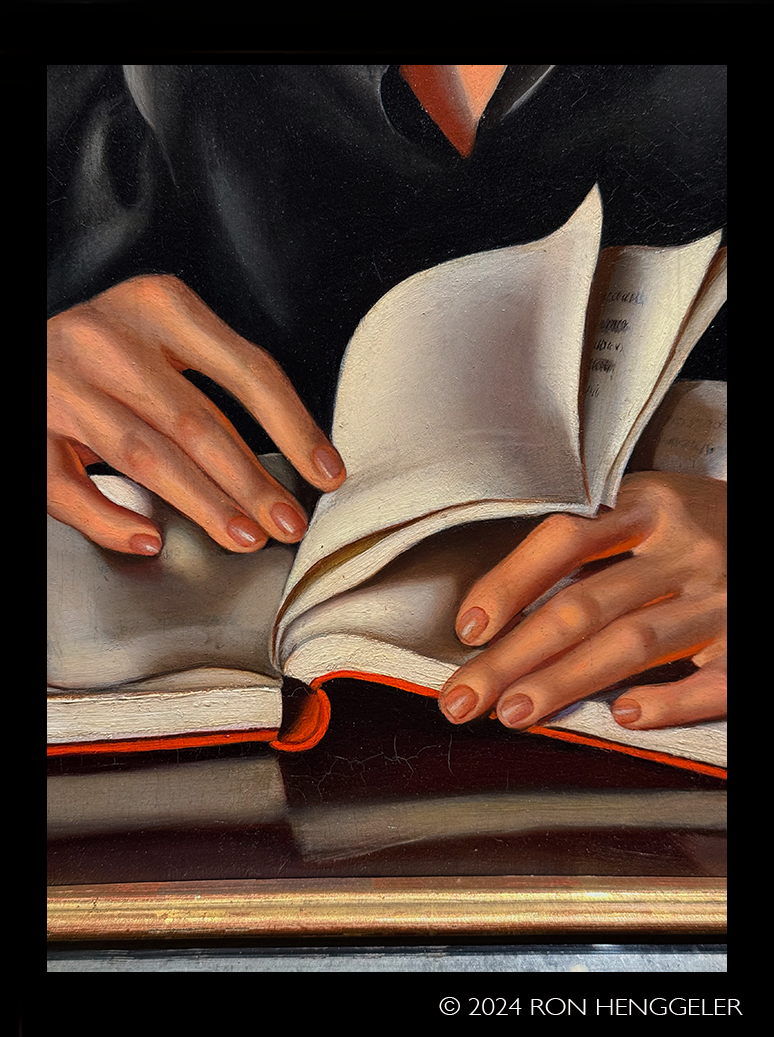

Wisdom (La sagesse), 1940-1941

Oil on panel

Colección Pérez Simón, Mexico

Presented at Tamara de Lempicka's 1941 exhibition in New York, this allegorical painting depicts a vision of wisdom personified by a woman engrossed in a book.

It is painstakingly studied in its details, evidenced in the smoothness of her face and the voluminousness of the red turban wrapped in firm folds atop her head, the latter of which Lempicka derived from Jan van Eyck's Portrait of a Man (1433; The National Gallery, London). |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Escape (Somewhere in Europe), 1940

Oil on canvas

Musée d'arts de Nantes, France, inv. 976.7.2.P

Capturing the gloom of the World War Il era, this painting, bearing the title Somewhere in Europe, was used for the press campaign leading up to Tamara de Lempicka's 1941 exhibitions organized by the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. It was a gesture of solidarity with Europeans at war, an inclination that culminated with the artist's fundraising efforts to support the British Red Cross.

It is within this context of involvement that we should view this painting. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Woman with Arms Crossed, ca. 1939

Oil on canvas

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Kizette de Lempicka-Foxhall, 1986, 1986.356 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

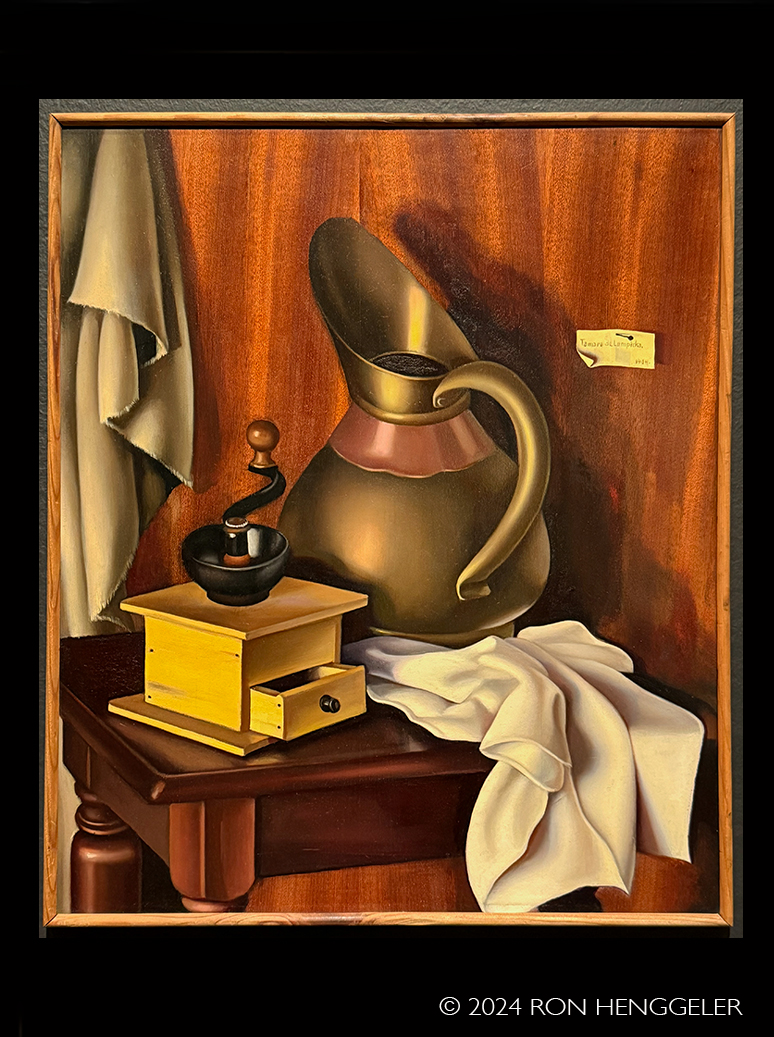

Still Life (The Coffee Grinder), 1941

Oil on panel

Musée d'arts de Nantes, France, inv. 976.7.4.P |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Still Life with Lemons and Plate,

ca. 1942

Oil on canvas

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Still Life of Fruit and Draped Silk, 1949

Oil on canvas board

Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Gift of Luis Aragón, 1986, 1986.174

This still life is distinctive for its juxtapositions of saturated colors, with a profusion of reds, yellows, oranges, and violets that stand out against the striped silk fabric.

A golden light enfolds the composition, quite unusually for an artist known for her predilection for shades of gray. The ripe fruits are polished and shining. They rest on a wooden surface featuring an old-fashioned tag with Tamara de Lempicka's signature on it; as a piece of exquisite technical finesse, presented as a sort of trompe loeil, it demonstrates her serene command of the craft on the threshold of the 1950s. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Fruit in a Bowl I

(Still Life on a Dark Background), 1949

Oil on canvas laid down on board

Musée d'arts de Nantes, France, inv. 976.7.3.P |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Studio in the Country, 1941

Oil on canvas

Musée d'arts de Nantes, France, inv. 982.28.1.P |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Still Life with a Print of Diana, ca. 1941

Oil on canvas

Collection of Cha Foxhall |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Composition in the Studio, 1941

Oil on panel

Museo Soumaya.Fundación Carlos Slim, Mexico City, 49319

Of the interiors of the Connecticut country house that Tamara de Lempicka painted around 1941, this work is more overt in its references to paintings by Flemish Old Masters. The artist here seeks to reproduce the dilation of space, to give a sense of the unknown lurking in every corner. The perspective into the rooms, the broom leaning against the wall, the hanging rag, and the shoe in the foreground seem to take inspiration from paintings of interiors by Samuel van Hoogstraten and Pieter de Hooch from the seventeenth century, during the Dutch Golden Age. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Arums

(Still Life with Arums and a Mirror), 1938

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

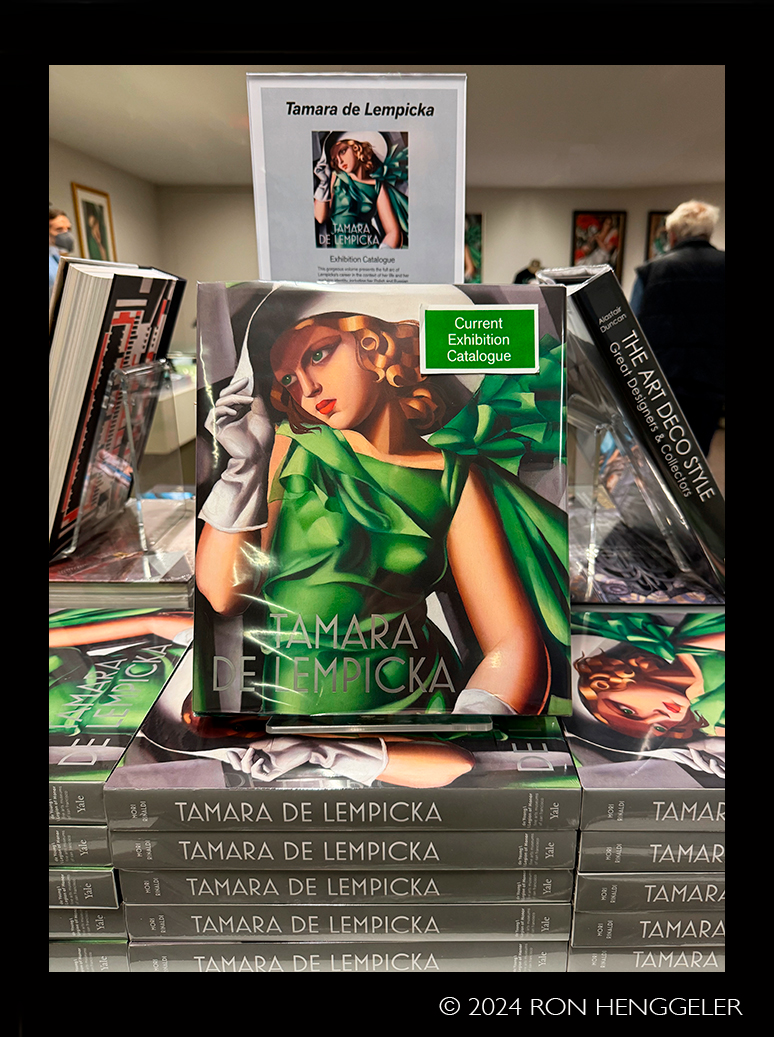

Tamara de Lempicka

October 12, 2024 - February 9, 2025 |

|

| |

Credits:

All of the text that accompanies the photos in this newsletter is respectfully taken from the walls at the museum. |

|