RON HENGGELER |

October 28, 2016

Impressions of The Brothers Le Nain: Painters of 17th-Century France

The Brothers Le Nain: Painters of 17th-Century France, which is now showing at the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco, is the first major exhibition in the United States devoted to the Le Nain brothers—Antoine (ca. 1598–1648), Louis (ca. 1600/1605–1648) and Mathieu (ca. 1607–1677). The presentation features more than forty of the brothers’ works to highlight the Le Nains’ full artistic production, and is organized in conjunction with the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and the Musée du Louvre-Lens in France. Here are my some of my photos of their paintings.

Jazz in his window-box overlooking the backyard. |

Three Men and a Boy, ca. 1640-1645Oil on canvasThree Men and a Boy has been generally interpreted as an unfinished group portrait of the brothers Le Nain. |

The Brothers Le Nain: Painters of 17th-Century France is the first major exhibition in the United States devoted to the Le Nain brothers—Antoine (ca. 1598–1648), Louis (ca. 1600/1605–1648) and Mathieu (ca. 1607–1677). The presentation features more than forty of the brothers’ works to highlight the Le Nains’ full artistic production, and is organized in conjunction with the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and the Musée du Louvre-Lens in France.https://legionofhonor.famsf.org/exhibitions/brothers-le-nain-painters-17th-century-france |

The Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1635Oil on canvasThe attribution of this work has been debated, and a strong case can be made for assigning it to Mathieu and for dating it to about 1635. The nervous, wispy brushwork of the shepherd's beards in the Adoration compares to the bearded Joachim in The Nativity of the Virgin from Notre-Dame Cathedral---Paris---Mathieu's earliest known masterpiece. The shepherd's faces reflect the study of live models, and the idealized countenance of the Virgin, silhouetted against the bright blue sky, also suggest Mathieu's hand. Although it is not known for what church this painting was created, the perspective of the steps suggest that it hung over the door of the left wall of a chapel. |

Detail of:The Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1635Oil on canvas |

The Nativity of the Virgin, ca. 1636Oil on canvasNotre-Dame Cathedral, Paris |

Detail of:The Nativity of the Virgin, ca. 1636Oil on canvasNotre-Dame Cathedral, Paris |

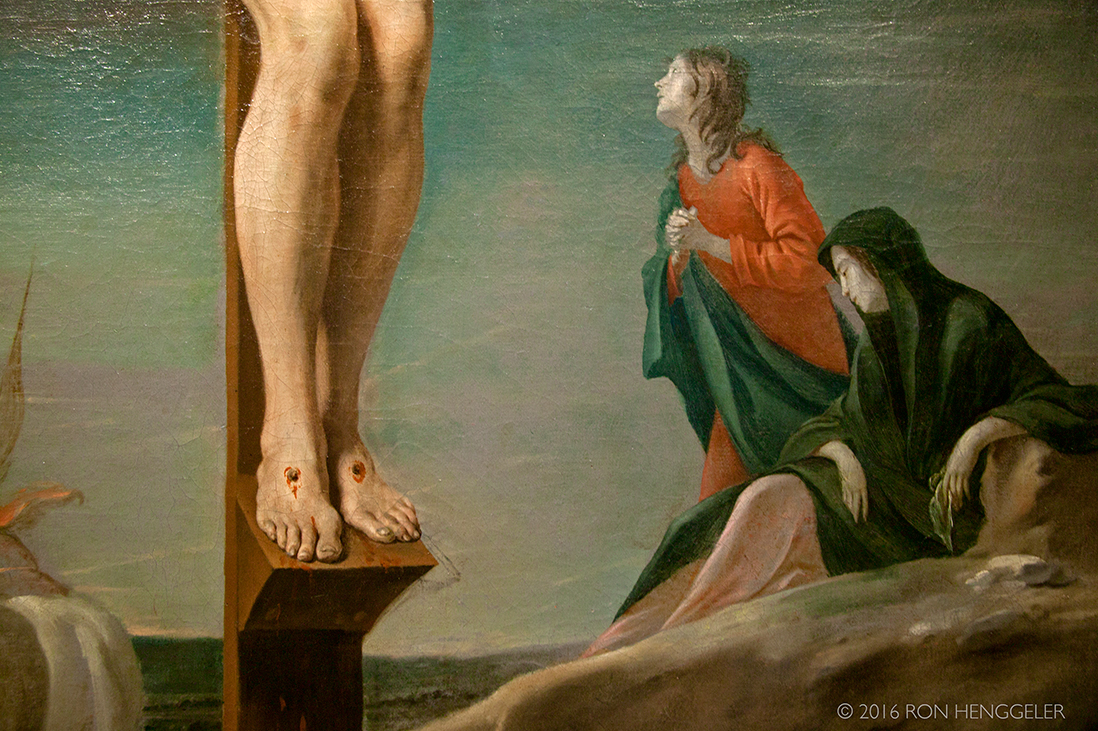

The Crucifixion, ca. 1645-1650Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Crucifixion, ca. 1645-1650Oil on canvas |

Nativity with a Torch, ca. 1635-1640Oil on canvasThe Le Nains painted several religious scenes set at night where the sole source of illumination---a flame or a fire---is represented within the picture. This new and exciting mode of painting was likely inspired by the works of artists who adopted the style of Caravaggio (Italian 1571-1610). Other similarities include the compressed scene and the overall sense of motion as the onlookers rush to view the brightly illuminated baby. |

Detail of:Nativity with a Torch, ca. 1635-1640Oil on canvas |

|

Christ on the Cross, ca. 1645-1650Oil on canvasThe dreamlike image of the Crucifixion is one of the most recent additions to the Le Nain's oeuvre. The sun and the moon appear simultaneously in the foreboding sky, reflecting the popular belief that darkness caused by a lunar eclipse engulfed the earth while Christ hung on the cross. Heightening the atmosphere of despair is the placement of Saint John the Evangelist and the Virgin Mary, alone and set like apparitions in the middle ground rather than at Christ's feet. The two soldiers on horseback, who ride toward the horizon, are likely the guards who, as Christ died and the earth shook, exclaimed: "Truly this was the Son of God!" (Matthew 27:45). |

Detail of:Christ on the Cross, ca. 1645-1650Oil on canvas |

About the ArtistsUnmarried and childless, the brothers lived and worked together in a tightly interwoven manner to produce some of the most enigmatic and arresting paintings of their time. Born in the small town of Laon, in the Picardy region of France, they were reportedly trained by an unknown artist who may have been traveling through their hometown. Very little is known about the brothers’ artistic activity until 1629, when Antoine Le Nain is documented as a painter in the guild of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Paris. Recognized by their peers as leaders in the contemporary artistic landscape, all three were elected early members of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in the French capital.Despite their renown, many important details of the brothers’ lives and work continue to elude historians. As the works were not individually signed, assigning a specific painting to a specific brother has long been a matter for debate.https://legionofhonor.famsf.org/exhibitions/brothers-le-nain-painters-17th-century-france |

Saint Michael Dedicating His Arms to the Virgin, ca. 1638Oil on canvasOriginally installed in a chapel in Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, this altarpiece undoubtedly commemorates King Louis XIII's victory over the Spanish on September 29, 1637, since that date coincides with Saint Michael's feast day. Soon after the victory, the king attended a special Mass at Notre-Dame, offering prayers to saint Michael for his assistance during the battle. The monarch's victorious commanding marshal, Charles de Schomberg, could be the patron of the altarpiece. An unquestioned masterpiece, the painting is an essay in compositional harmony, tonal unity, and lyric naturalism. |

Detail of:Saint Michael Dedicating His Arms to the Virgin, ca. 1638Oil on canvas |

Detail of:Saint Michael Dedicating His Arms to the Virgin, ca. 1638Oil on canvas |

Active in Paris during the 1630s and 1640s, the brothers are today best known for their startlingly realistic depictions of the poor. Painters of altarpieces, portraits and allegories, the brothers’ work was rediscovered in the 19th century by such art historians as Champfleury, and influenced many artists including Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet. The brothers then became famous as “painters of reality,” admired for their deeply sympathetic and affecting portrayals of hard-working men and women. In these paintings, we see smiling field laborers, city beggars with deadpan expressions, mothers cradling infants with perfect intimacy, and children that dance and play music with a lack of pretension. The Museums’ Peasants before a House is one of the finest examples of this subject.https://legionofhonor.famsf.org/exhibitions/brothers-le-nain-painters-17th-century-france |

Detail of:Saint Michael Dedicating His Arms to the Virgin, ca. 1638Oil on canvas |

The Nativity of the Virgin, ca. 1636Oil on canvasNotre-Dame Cathedral, ParisA wet nurse holds the infant Mary in the foreground, while in the background, the Virgin's mother, Saint Anne, recuperates from labor. Mary's father, Saint Joachim, looks on adoringly, joined by angels, including one who prepares a swaddling blanket. This is one of three altarpieces by the Le Nains that are recorded in Notre-Dame Cathedral before the end of the eighteenth century. By the mid-1630's, the brothers commanded the respect and possessed the talent necessary for such prestigious commissions. |

In their day, the brothers were celebrated not only as genre painters, but also as portraitists and painters of religious subjects.Patrons of the brothers included Anne of Austria, Cardinal Mazarin, and the captain of the royal musketeers, le comte de Tréville—one of the inspirations for Alexandre Dumas’s celebrated novel The Three Musketeers.https://legionofhonor.famsf.org/exhibitions/brothers-le-nain-painters-17th-century-france |

Detail of:The Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1635Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1635Oil on canvas |

The Resting Horseman, ca. 1640Oil on canvasThis outdoor scene perhaps depicts tenant farmers who oversaw the land for town-dwelling landlords. Their general well-being is shown in the woman's smile, the boy's affectionate gesture, and the prominence of animals. The brass container balanced on the woman's head presumably holds milk, a sign of relative prosperity as dairy products were rarely consumed by the rural poor. The horse was a valuable asset and a status symbol, since most farmers used only oxen or donkeys to work their land. |

Landscape with Peasants, ca. 1645Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Resting Horseman, ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Resting Horseman, ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Resting Horseman, ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

The Peasant Family, ca. 1642Oil on canvas |

The Peasant Family, ca. 1642Oil on canvasThis painting may pay tribute to the charitable work of females. The neatly dressed woman at left, with a younger friend seated at right, has evidently brought food to a poor family's house. In seventeenth-century Paris, aristocratic women ran some of the most important charitable organizations in the city. The Filles de la Charite (Daughters of Charity) wore blue-gray habits with white headdresses---virtually the same outfits as the woman in the painting. The very large size of the painting suggests that it was commissioned, rather than sold on the open market, likely by someone who belonged to the culture of Catholic charity---if not the Daughters of Charity. The deft use of white highlights to indicate glints of light off glassy surfaces and the handling of the white colors is typical of Louis. |

Detail of:The Peasant Family, ca. 1642Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Peasant Family, ca. 1642Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Peasant Family, ca. 1642Oil on canvas |

Peasant Interior with Old Flute Player, ca. 1642Oil on canvasThe subjects of this painting---the poor, dressed in humble but decent clothing, served as exemplars in pious circles in the Le Nains' Paris. As in other paintings by the brothers, the white table cloth, the glass of red wine, and the broken bread, must refer to the Eucharist. Jean-Jacques Olier, the Le Nain's parish priest, wrote that the Eucharist went hand in hand with the poor, as both stood for sacrifice. Olier believed that even the humblest of meals should be treated as a kind of Eucharist. The painting's serenity---the smiling boy at the venter---give the impression that being poor, or enduring sacrifice, is virtuous. The seated, barefooted mother at right evokes the Revolt of the Nu-Pieds (the barefoot ones---or downtrodden poor) in Normandy in 1639. She also recalls the Virgin Mary, whom Olier exhorted thew faithful to venerate. |

Detail of:Peasant Interior with Old Flute Player, ca. 1642Oil on canvas |

|

The Last Supper, ca. 1650'sOil on canvas |

|

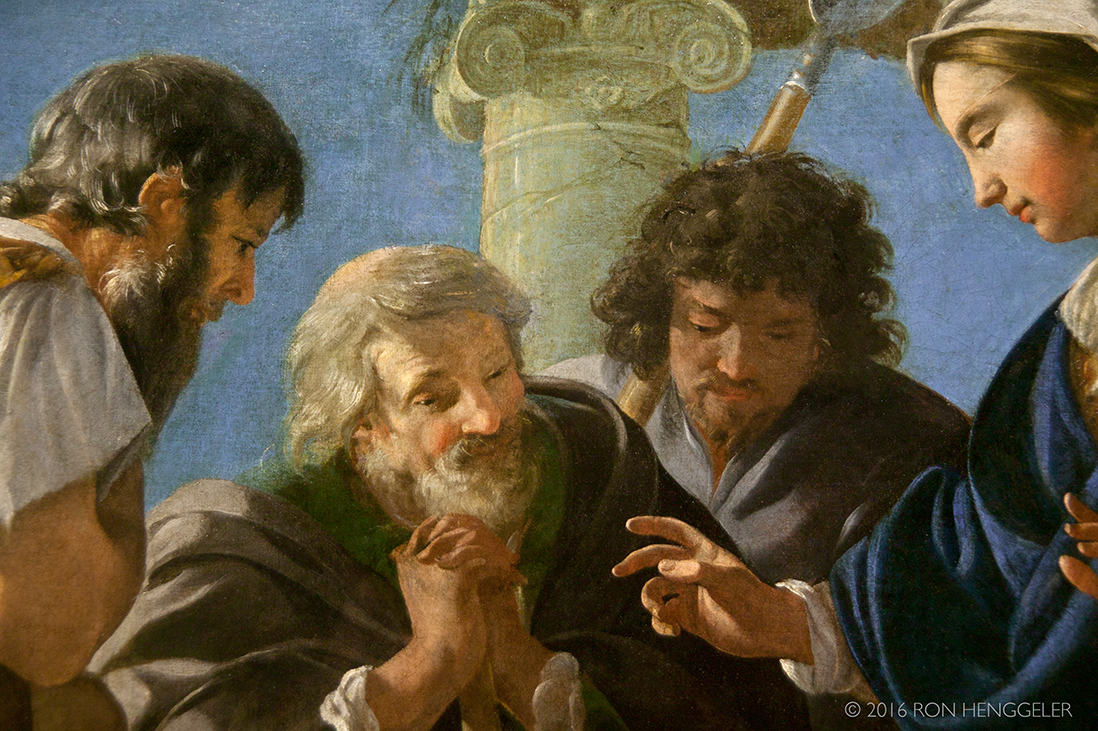

The Denial of Saint Peter, ca. 1645Oil on canvasAccording to the Gospels, after Christ was arrested, Peter followed him into the courtyard of the high priest Caiaphas. As Peter waited, three people asked him if he was a disciple of Christ, which he denied. As he spoke his third denial, a rooster crowed, and Peter remembered Christ's prophecy: " Before the rooster crows, you will disown me three times. " Realizing his betrayal, Peter sought a place to weep. Here, the three figures, including a servant girl, represent each of his denials. |

The Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1635-1640Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Adoration of the Shepherds, ca. 1635-1640Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Penitent Magdalene, ca. 1642Oil on canvas |

|

Soldiers Playing Cards (A Quarrel), ca. 1640Oil on canvasThis game is about to erupt in violence: the standing man raises his sword, while the soldier seated left of the drum, which serves as an improvised table, tensely grasps his weapon. At far right, the young redhead in tattered garments with bare feet stares with his mouth agape at a card on the ground, as if just discovering he has been cheated. At far left, thew older man looks at the viewer with cold blue eyes---providing silent commentary on the consequences of gambling. |

Detail of:Soldiers Playing Cards (A Quarrel), ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

Portrait of the conte de Treville, ca. 1644Oil on canvasThis dashing and nobly outfitted gentleman is Jean-Armand du Peyrer, comte de Treville (1578-1672), captain of the esteemed Mousquetaires de la Garde, or royal musketeers, charged with protecting the king. he inspired a swashbuckling character of the same name in Dumas's famous novel, The Three Musketeers (1844). Embroiled in a failed plot to overthrow Richelieu in 1642, Treville was briefly sent into exile by Louis XIII. Within a year however, both Richelieu and the king were dead. The portrait, signed and dated 1644, was created a year after Anne of Austria rewarded Treville for his loyalty by making him a count. No longer a musketeer, he does not carry their distinguishing musket. This ambitious painting, with its meticulous brushwork and mastery of eloborate textures---lace, leather, metal---marks at least one of the brothers among the finest mid-seventeenth century portraitists. |

Detail of:Portrait of the conte de Treville, ca. 1644Oil on canvas |

Allegory of VictoryOil on canvas |

Detail of:Portrait of the conte de Treville, ca. 1644Oil on canvas |

|

Allegory of VictoryOil on canvas |

The Concert, 1650's or 1660'sOil on canvas |

Detail of:The Concert, 1650's or 1660'sOil on canvas |

Bacchus and Ariadne, ca. 1635Oil on canvas |

Detail of:Bacchus and Ariadne, ca. 1635Oil on canvas |

|

The Penitent Magdalene, ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

Detail of:The Nativity of the Virgin, ca. 1636Oil on canvasNotre-Dame Cathedral, Paris |

Detail of:The Nativity of the Virgin, ca. 1636Oil on canvasNotre-Dame Cathedral, Paris |

Detail of:The Nativity of the Virgin, ca. 1636Oil on canvasNotre-Dame Cathedral, Paris |

The Painter's Studio, 1650's or 1660'sOil on canvas |

Woman with Five Children, 1642Oil on copper |

The Family Prayer, 1645Oil on copper |

Detail of:The Family Prayer, 1645Oil on copper |

Portraits in an Interior, 1647Oil on copper |

The Entombment of Christ, 1650'sOil on canvas |

Peasant Interior, ca. 1640Oil on canvasDressed like a pilgrim, with his traveler's cape, walking stick, and broad-brimmed hat, the man at left eats a bowl of mash and is offered a glass of wine. The matriarch, whose own clothes are ragged, disperses this charity for the purest of reasons---to help one's neighbor. The painting illustrates the beliefs of ecclesiastics like the Le Nain's parish priest, Jean-Jacques Olier, who were part of a new wave of Catholic charity in seventeenth-century Paris. |

Detail of:Peasant Interior, ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

Detail of:Peasant Interior, ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

Detail of:Peasant Interior, ca. 1640Oil on canvas |

Peasants before a House, ca. 1640Oil on canvasThese contemplative figures--neither destitute nor desperate---are likely the tenants of this property. The stone building is typical of the Picardy region, with the staircase leading to the upper living space. For the Le Nain's viewers, the boy's bare feet likely recall the Revolt of the Nu-Pieds (the barefoot ones) in 1639, when Norman peasants protested a tax on salt. In 1643, Vincent de Paul delivered a sermon in which he praised the rural poor "for their great humility: they don't boast of what they have . . . but act in a straightforward manner . . . content with what they have". Perhaps the original owner of this painting shared such sympathies. |

The Painter's Studio, ca. 1640-1645Oil on panelThis painting of the brothers asserts their success and social status, underscored by their fancy dress.The seemingly youngest man sits at the easel and can reasonably be identified as Mathieu, the youngest brother. Standing to the far right dressed in black is probably Antoine, likely the work's creator given such stylistic clues as ropelike hair and staccato highlights; he holds a painter's palette and gazes at the viewer--as is commonplace in a self-portrait. Louis, then, could be the brother wearing the red cape at center. The standing man at left and the seated man who poses could be the Le Nain's two older brothers: Isaac II and Nicolas. The portrait at lower right may represent the patriarch of the family, Isaac Le Nain. the difficulty to identify the figures in The Painter's Studio conclusively is emblematic of the "Le Nain problem": it appears they intentionally obscured which of them painted which of their pictures. |

Newsletters Index: 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006

Photography Index | Graphics Index | History Index

Home | Gallery | About Me | Links | Contact

© 2017 All rights reserved

The images are not in the public domain. They are the sole property of the

artist and may not be reproduced on the Internet, sold, altered, enhanced,

modified by artificial, digital or computer imaging or in any other form

without the express written permission of the artist. Non-watermarked copies of photographs on this site can be purchased by contacting Ron.