RON HENGGELER |

May 10th, 1869

The Transcontinental Railroad

May 10th marks the anniversary of one of the most pivotal events and achievements in the history of the United States, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad.

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad May 10, 1869, is recognized as one of our country’s biggest achievements and one of mankind’s biggest accomplishments. It’s been compared to the Apollo 11 moon landing in terms of the vision, dedication, innovation and collaboration needed to connect the country with a ribbon of rail.This text respectfully taken from: Inside Track |

A poster announcing the joining of the Transcontinental Railroad on May 10th,1869 hangs in the bar of the Big 4 Restaurant on Nob Hill in San Francisco. |

Sacramento's riverfront during the time of construction of the Transcontinental Railroad |

|

|

"Sacramento Railroad Station" 1874Oil on canvasby William Hahn |

The First Transcontinental Railroad was a 1,912-mile continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail network at Omaha, Nebraska/Council Bluffs, Iowa with the Pacific coast at the Oakland Long Wharf on San Francisco Bay. |

Sacramento California |

Sacramento California |

Sacramento's riverfront during construction of the Transcontinental Railroad |

The manual labor to build the Central Pacific's roadbed, bridges and tunnels was done primarily by many thousands of emigrant workers from China under the direction of skilled non-Chinese supervisors. The Chinese were commonly referred to at the time as "Celestials" and China as the "Celestial Kingdom." Initially, Central Pacific had a hard time hiring and keeping unskilled workers on its line, as many would leave for the prospect of far more lucrative gold or silver mining options elsewhere. Despite the concerns expressed by Charles Crocker, one of the "big four" and a general contractor, that the Chinese were too small in stature and lacking previous experience with railroad work, they decided to try them anyway. After the first few days of trial with a few workers, with noticeably positive results, Crocker decided to hire as many as he could, looking primarily at the California labor force, where the majority of Chinese worked as independent gold miners or in the service industries (e.g.: laundries and kitchens). Most of these Chinese workers were represented by a Chinese "boss" who translated, collected salaries for his crew, kept discipline and relayed orders from an American general supervisor. Most Chinese workers spoke only rudimentary or no English, and the supervisors typically only learned rudimentary Chinese. From Wikipedia |

|

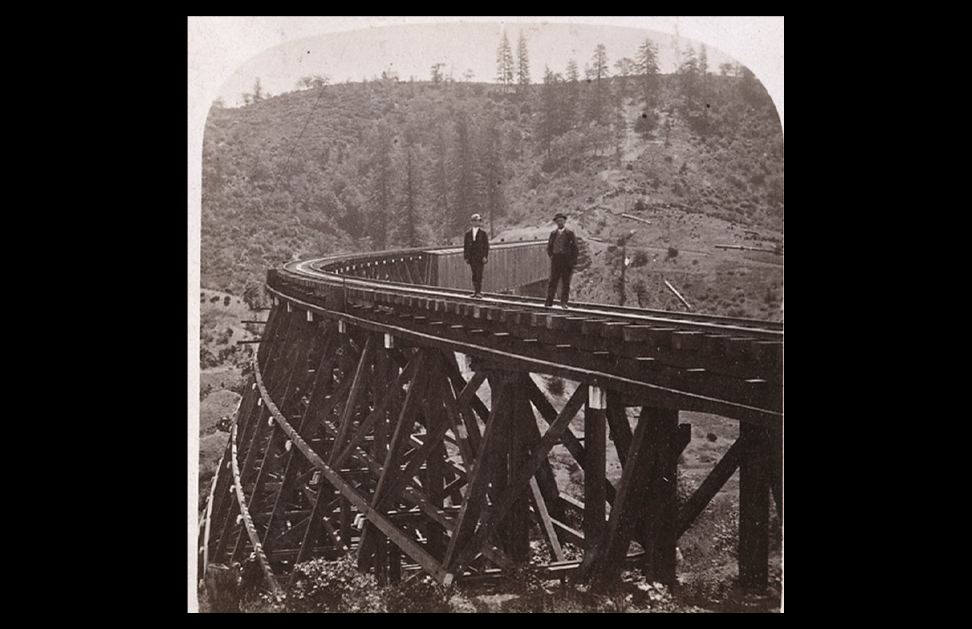

Labor-saving devices in those days consisted primarily of wheelbarrows, horse or mule pulled carts, and a few railroad pulled gondolas. The construction work involved an immense amount of manual labor. |

For the complete story of the railroad, and to view a remarkable collection of photos, I recommend a visit to the online Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum |

|

|

Donner Summit |

|

Read about the Chinese-American contribution to the Transcontinental Railroad, at theCentral Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum |

Along with the development of the atomic bomb, the digging of the Panama Canal, and landing the first men on the moon, the construction of a transcontinental railroad was one of the United States' greatest technological achievements. Railroad track had to be laid over 2,000 miles of rugged terrain, including mountains of solid granite.Read this complete article at Digital History. |

|

|

At one point, Chinese workers were lowered in hand-woven reed baskets to drill blasting holes in the rock. They placed explosives in each hole, lit the fuses, and were, hopefully, pulled up before the powder was detonated. Explosions, freezing temperatures, and avalanches in the High Sierras killed hundreds. When Chinese workers struck for higher pay, a Central Pacific executive withheld their food supplies until they agreed to go back to work.An English-Chinese phrase book from 1867 translated the following phrases into Chinese:

Read this complete article at Digital History. |

Chinese laborers made up a majority of the Central Pacific workforce that built out the transcontinental railroad east from California. The rails they laid eventually met track set down by the Union Pacific, which worked westward. On May 10, 1869, the golden spike was hammered in at Promontory, Utah.150 Years Ago, Chinese Railroad Workers Staged the Era's Largest Labor StrikeRead the article by Chris Fuchs here. |

For the complete story of the railroad, and to view a remarkable collection of photos, I recommend a visit to the online Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum |

|

|

|

|

|

For the complete story of the railroad, and to view a remarkable collection of photos, I recommend a visit to the online Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum |

|

|

|

|

To view a remarkable collection of photos,visit the online Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum |

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Hell on Wheels"Numerous "hell on wheels" towns proliferated along the Union Pacific construction route from Omaha, Nebraska, to Promontory Summit, Utah. The towns were famous for their rapid growth and infamous for their lawlessness.Read the complete article at:The Linda Hall Library |

|

2019 marks the 150th anniversary of the introduction of large numbers of Chinese workers on the construction of the first transcontinental railway across North America. May 10, 2019 is the 150th anniversary of Leland Stanford’s driving the famous “golden spike” to connect the Central Pacific and Union Pacific at Promontory Summit, Utah, to complete the line. The labor of these Chinese workers (who eventually numbered between 10-12,000 at any one moment) was central to creating the wealth that Leland Stanford used to found Stanford University. But these workers have never received the attention they deserve. We know relatively little about their lives. What led them to come to the United States? What experiences did they have in their arduous work? How did they live their daily lives? What kinds of communities did they create? How did their work on the railroad change the lives of their families in China and how did it change the lives of the workers themselves, both those who returned to China or went elsewhere after the railroad’s completion and those who stayed in the U.S.?Click below to read the full article.Respectfully taken from:Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University |

|

|

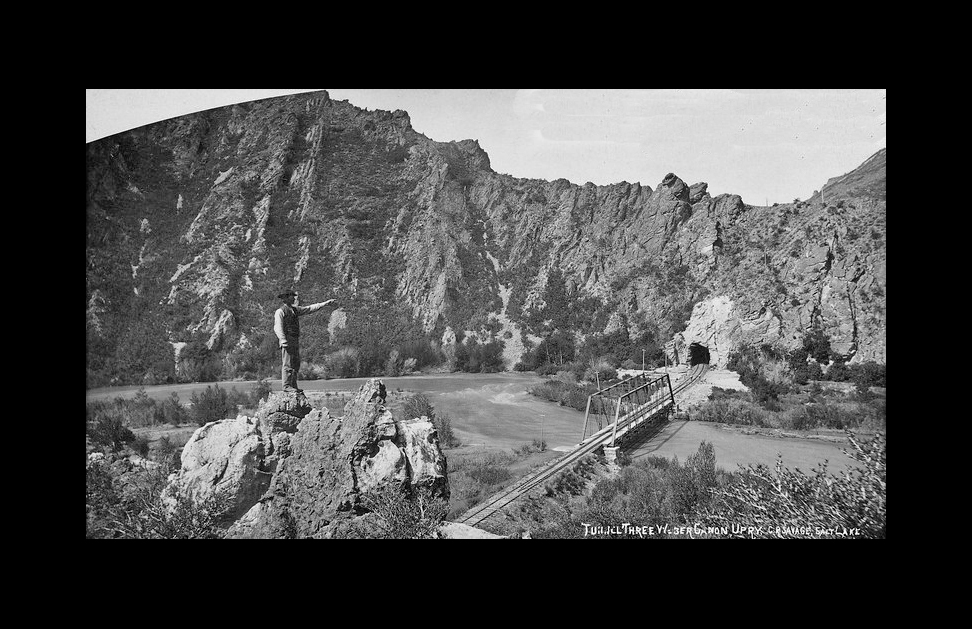

Photo by Sacramento photographer Alfred A. Hart |

|

|

At 12:47 p.m. on Monday, May 10, 1869, Western Union telegrapher W.N. Shilling sent a message that was eagerly anticipated all across the country: 'D-O-N-E.' |

To drive the final spike, Stanford lifted a silver spike maul and drove the spike into the tie, completing the line. Stanford and Hewes missed the spike, but the single word "done" was nevertheless flashed by telegraph around the country."The Last Spike" by Thomas HillThe famous painting is on permanent display at the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento. |

In the United States, the event has come to be considered one of the first nationwide media events. With the word D O N E flashed by telegraph across the country, church bells in towns and cities across the continent began to peal and the cannons from ships boomed in the harbors. People rejoiced with fireworks, parades, brass bands, celebrations, and triumphal arches. In San Francisco, all 121 cannons at Fort Point were fired simultaneously. |

The locomotives were moved forward until their cowcatchers met, and photographs were taken. Immediately afterwards, the golden spike was removed and replaced with a regular iron spike.Photo by Charles R. Savage |

|

Between 1864 and 1869, thousands of Chinese migrants toiled at a grueling pace and in perilous working conditions to help construct America’s first Transcontinental Railroad. The Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project seeks to give a voice to the Chinese migrants whose labor on the Transcontinental Railroad helped to shape the physical and social landscape of the American West. The Project coordinates research in North America and Asia in order to publish new findings in print and digital formats, support new and scholarly informed school curriculum, and participate in conferences and public events. Click below to read the full article.Respectfully taken from:Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University |

The Central Pacific released Chinese workers in April 1869 with the completion of the railroad at Promontory, Utah. Racial tensions increased in the West as the workers returned to California in search of employment. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act that barred future Chinese immigration and denied naturalization for those already in the U.S. The Act stood in place for 60 years until President Franklin Roosevelt repealed it in 1943 during World War II.Read the complete article at:The Linda Hall Library |

|

|

|

|

|

Inside a Sierra snowshed |

A Native American overlooks the newly completed transcontinental railroad in Sacramento, c. 1867 |

Many of the railroad's builders viewed the Plains Indians as obstacles to be removed. General William Tecumseh Sherman wrote in 1867: "The more we can kill this year, the less will have to be killed the next year, for the more I see of these Indians the more convinced I am that they all have to be killed or be maintained as a species of paupers."Read this complete article at Digital History. |

The wanton slaughter of the American bison was a byproduct of the Trancontinental Railroad. Largely a nineteenth-century tale, the final stage from 1867 to 1884 was notable for the fury of the slaughter for hides and other products. With the completion of the railroad in 1869, it split the enormous Plains herd in the heart of the buffalo's range, a process that would be repeated again and again. |

As the populations of the United States pushed West in the 19th century, a lucrative trade for the fur, skin, and meat of the American bison began in the great plains. Bison slaughter was further encouraged by the US government as a means of starving out or removing Native American populations that relied on the bison for food. Hunting of bison became so prevalent that travelers on trains in the Midwest would shoot bison during long-haul train trips. |

Once numbering in the hundreds of millions in North America, the population of the American bison decreased to less than 1000 by 1890, resulting in the near-extinction of American bison. Thanks in large part to conservation efforts undertaken by Theodore Roosevelt and by the US government, there are now over 500,000 bison in America. |

The settlement of the West changed the environment in numerous ways. One well-known example is the mass killing of American bison. In 1889, William T. Hornady, Superintendent of the National Zoological Park, wrote a detailed report of what he termed the "extermination" of the species. That report appears in Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920. |

Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford, and Collis Huntington

|

|

Crocker's mansion was on Nob Hill where Grace Cathedral is now located. Charles Crocker built a mansion next to his own (at Jones and California) for his son William as a wedding gift. When William's mansion burned in April 1906, the Art world lost 35 Degas paintings. William was an avid collector of Degas. |

|

The Hopkins mansion stood on Nob Hill at California and Mason where the Intercontinental Mark Hopkins Hotel is located today. The mansion cost three and a half million dollars in 1878, about 95 million in today's money. |

Huntington was worth 1.6 billion dollars when he passed away in 1900. |

The Huntington mansion that burned in 1906 is now the elegant Huntington Park across the street from the Big 4 Restaurant.For more on the Huntington mansion and Huntington Park, and to see relics from the mansion that I discovered in 2015, go to:http://www.ronhenggeler.com/Newsletters/2015/10.25/Newsletter.html |

"On May 10, 1869, Leland Stanford participated in the ceremonial driving of the last railroad spike, a gold spike, that made the U.S. Transcontinental Railroad possible. The Stanford Historical Society will examine this legacy in a year-long celebration of the 150th anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad." Learn about this celebration at Stanford University. |

In the 19th century, the Stanford mansion was located on Nob Hill at California Street and Powell. (Note the Mark Hopkins mansion under construction on ther right.) The mansions burned in April 1906. The Stanford Court Hotel now stands at this site. |

The rails from Promontory were recycled during World War II, but the cermonial gold spike lives on at Stanford University's Cantor Arts Center. |

Newsletters Index: 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006

Photography Index | Graphics Index | History Index

Home | Gallery | About Me | Links | Contact

© 2023 All rights reserved

The images oon this site are not in the public domain. They are the sole property of the

artist and may not be reproduced on the Internet, sold, altered, enhanced,

modified by artificial, digital or computer imaging or in any other form

without the express written permission of the artist. Non-watermarked copies of photographs on this site can be purchased by contacting Ron.