| |

April 7, 2025

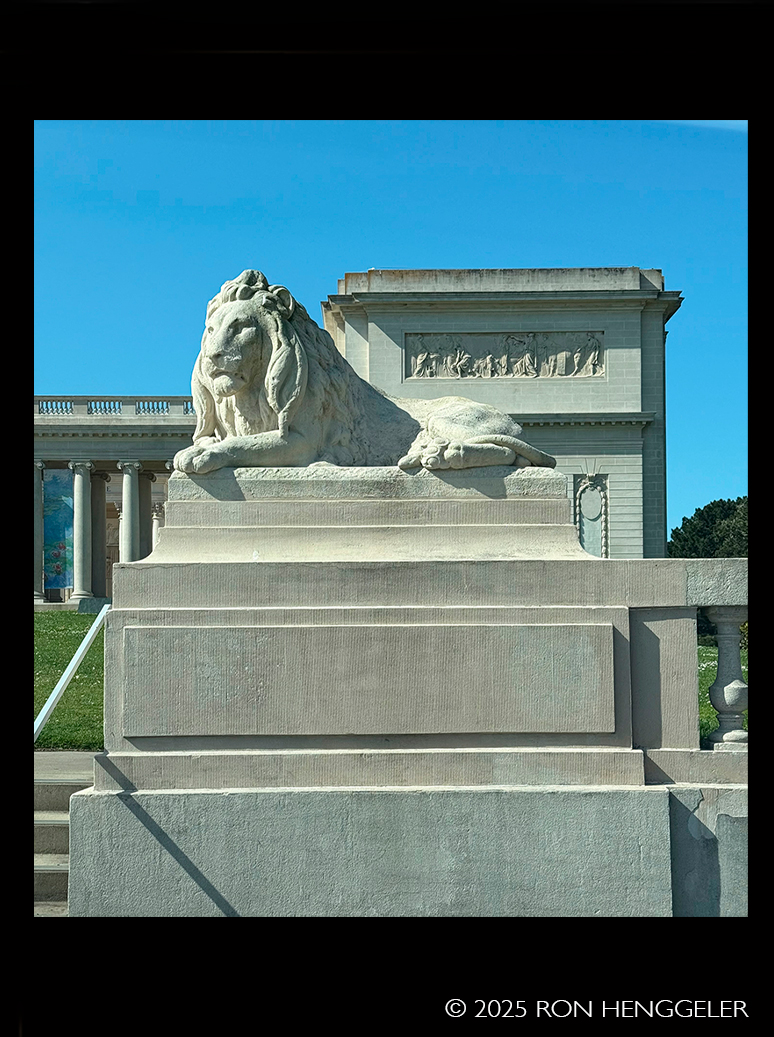

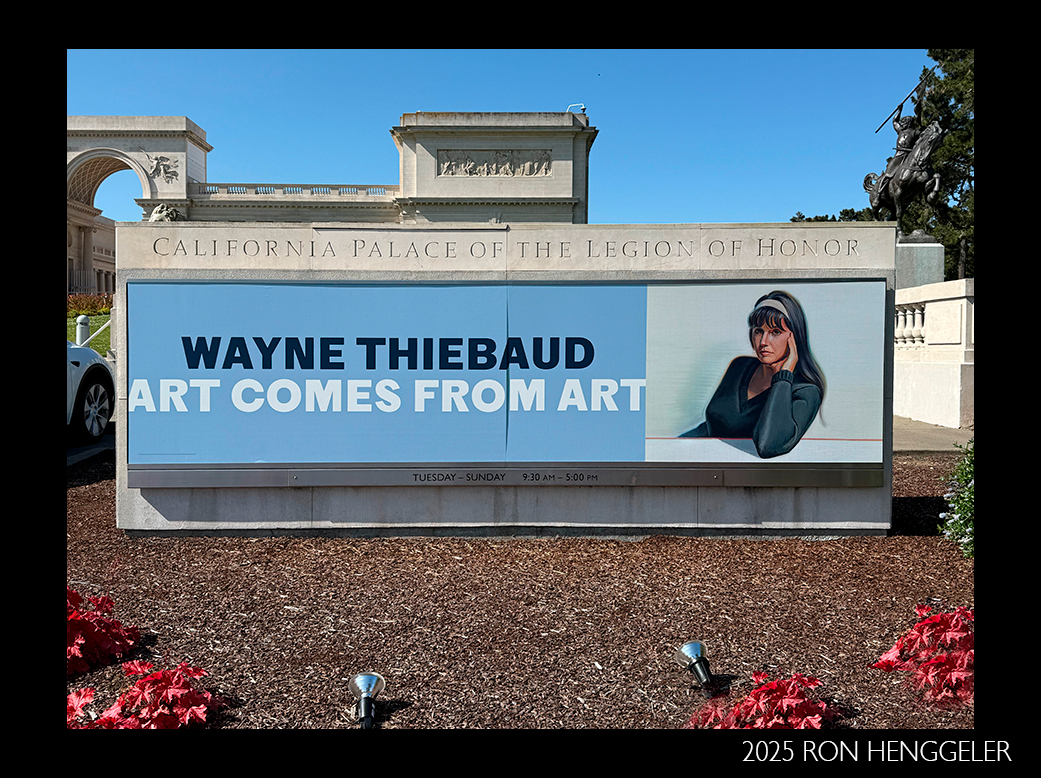

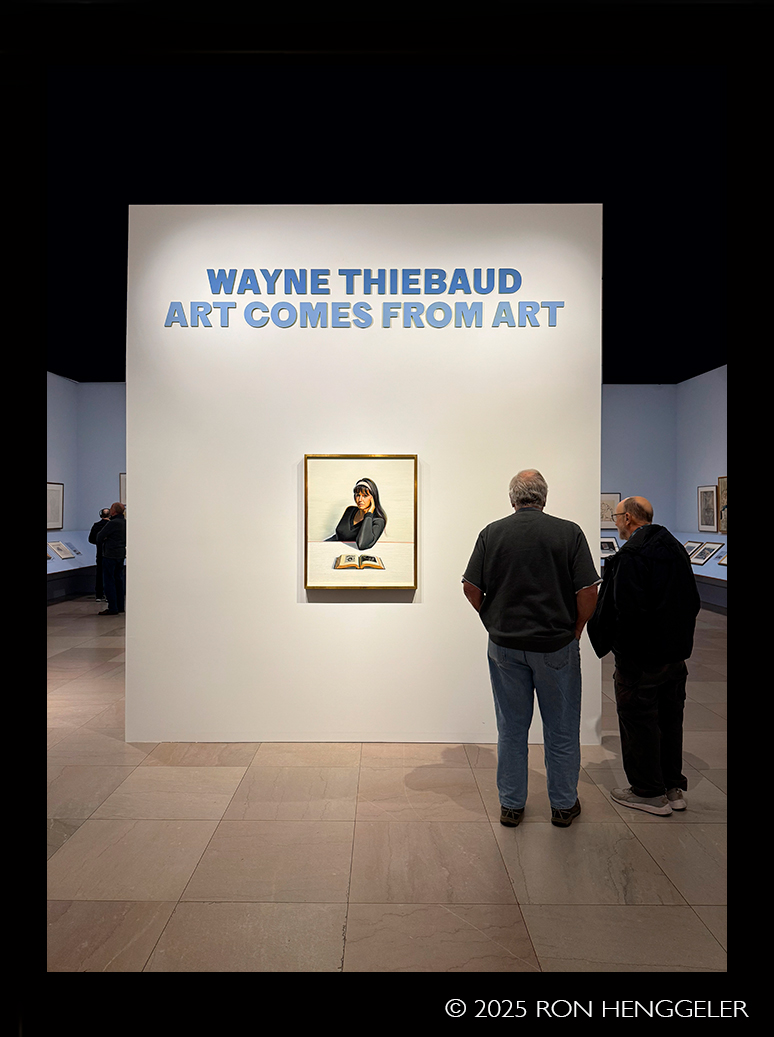

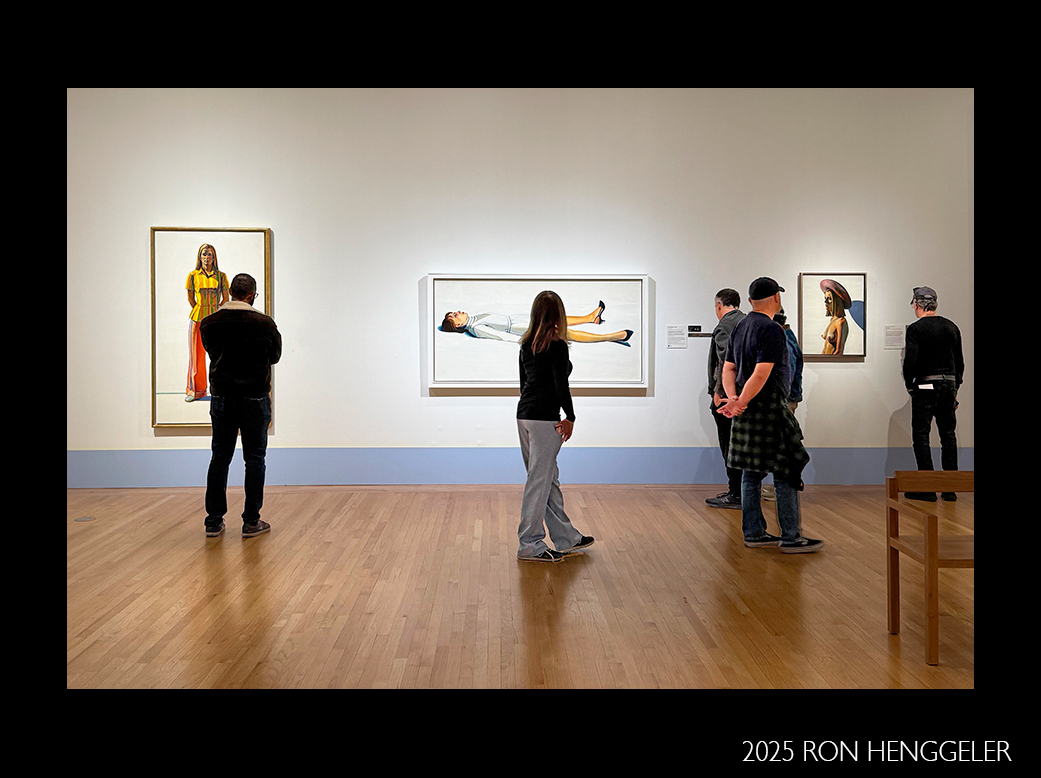

ART COMES FROM ART

Wayne Thiebaud at the Legion of Honor

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

"If painting and photography are about anything, if those museums, if art history means anything to us, it's the continual, refreshing confrontation of what human beings can be, have been, should be, might be, should ever be, in our own work."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

|

|

| |

A short video that coinsides with the Wayne Thiebaud exhibit at the Legion of Honor. Click here: Art Thief: Lessons from Wayne Thiebaud

Credits: The texts with the photos in this newsletter were taken from the placards on the walls next to each painting at the museum exhibit. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

At the Legion of Honor Museum until August 17, 2025-----

"Like museums, art history is a grand exotic game preserve with all kinds of potential for seeing. A place where you go to experience all the extreme attitudes of human beings-to check on yourself, extend yourself, criticize yourself or find out about yourself".

Wayne Thiebaud

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

It's the Legion of Honor's 100th anniversary! |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

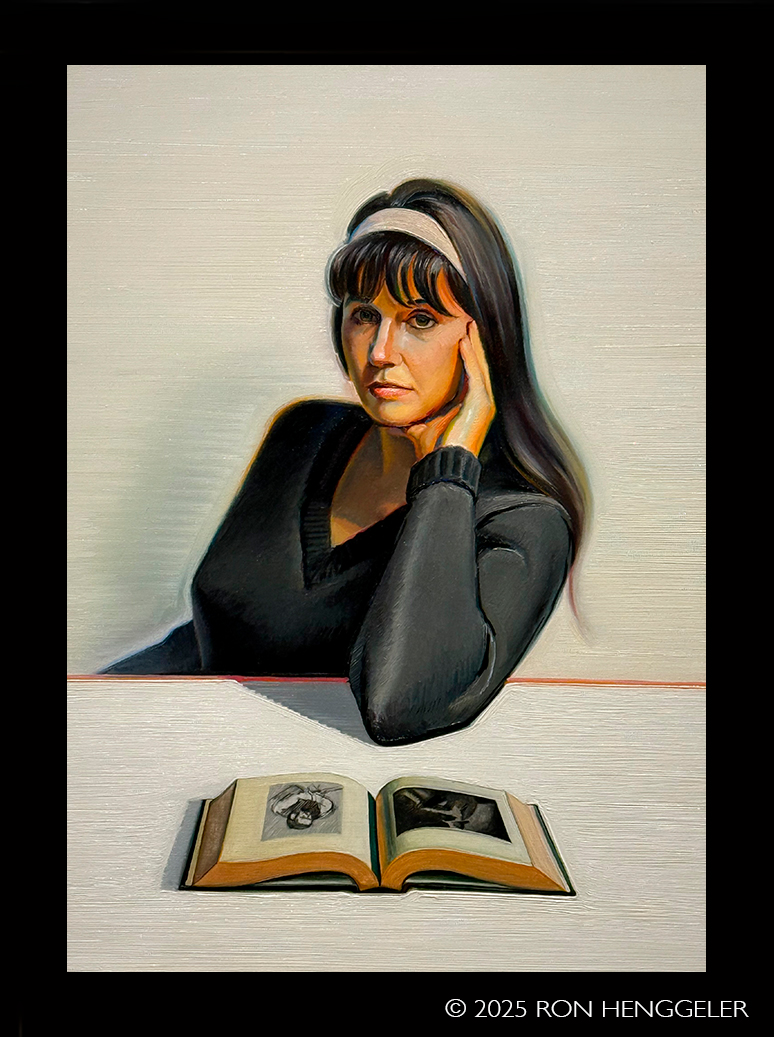

Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book,

1965-1969

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's most eloquent tribute to art, art history, and appropriation depicts the artist's wife, a filmmaker who was also his muse and model. She is seated near an open art book with reproductions of French drawings by theImpressionist Edgar Degas and the Post-ImpressionistGeorges Seurat. While Betty Jean Thiebaud is her husband's model, she may not be his only source of inspiration, asSeurat and Degas also seem to be candidates for this role.

This composition has a distinguished art historical ancestry, possibly incorporating artworks created by Albrecht Dürer, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Edgar Degas, and PabloPicasso. Thiebauds portrait of his wife may draw upon all, some, or none of these images, but they suggest the degree to which this painting-like many of the artist's works-is a multilayered record of earlier artworks, whether consciously

referenced or subconsciously recalled.

Crocker Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wayne Thiebaud, 1969.21 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

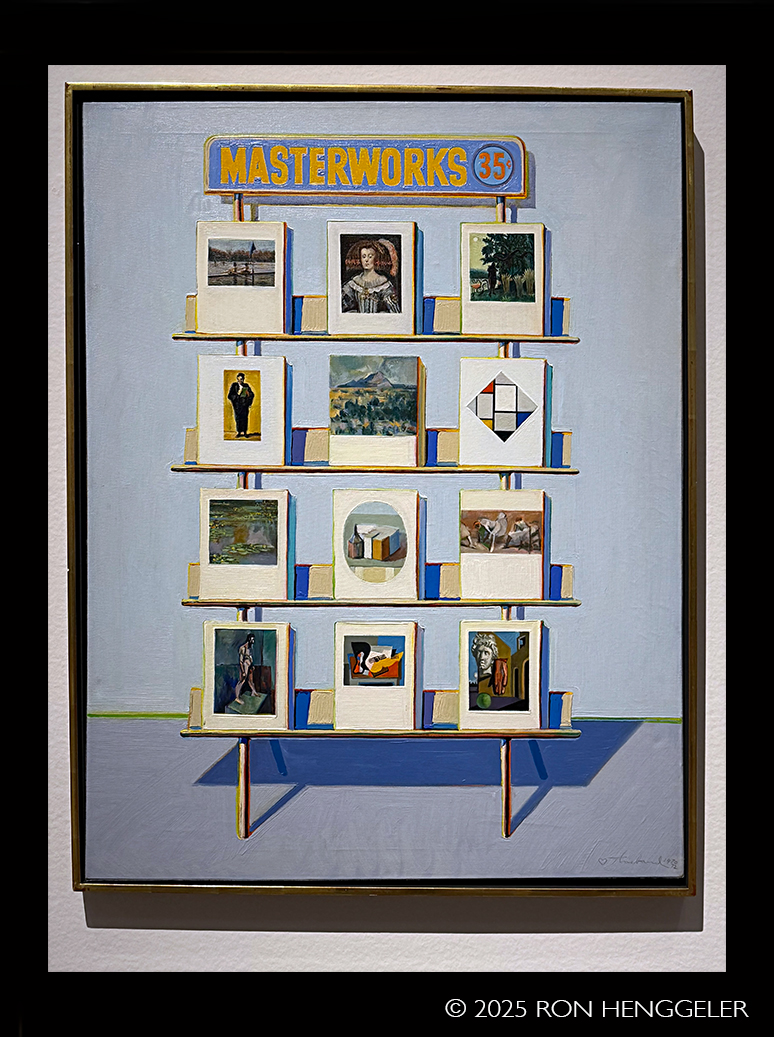

35 Cent Masterworks, 1970, 1972

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud identified many of his artist heroes-and targets for theft-in this painting, which depicts a display rack holding thirty-five-cent reproductions of twelve valuable "masterworks," spanning from Diego Velázquez to Giorgio Morandi. It is not clear whether Thiebaud is suggesting that great works of art should be accessible to everyone, or whether their value has been cheapened by mass reproduction.

Either way, he pays tribute to the timeless-and priceless-value of his art historical ancestry: "The real joy of being a painter for me is quite simple. It's that wonder of being hooked up with a whole community of people you love and admire throughout history."

Wayne Thiebaud Foundation, Sacramento, California |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

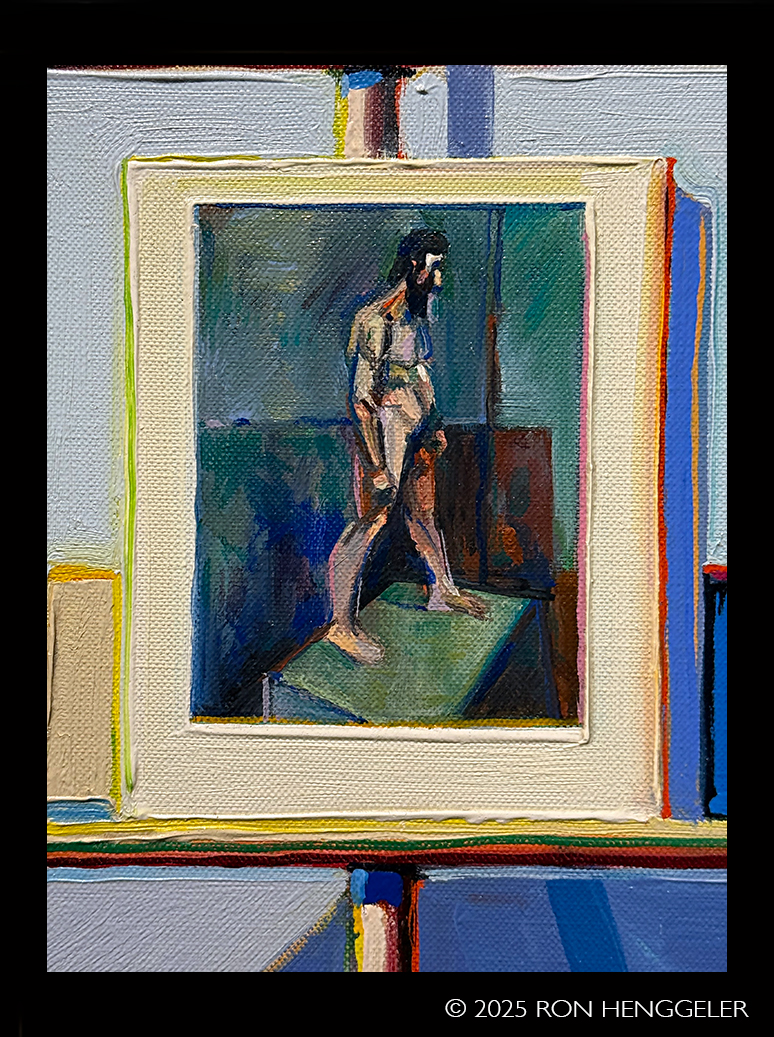

Detail of:

35 Cent Masterworks

Thiebaud reproduced miniature versions of these twelve historical artworks in his painting 35 Cent Masterworks. All of the artists are European, with the exception of the American realist Thomas Eakins, and six of the twelve are French. Discussing great artists from the past and the present, Thiebaud observed: "I admire them so much and I want people to look at them and get into it. Not just take a peek at them. It is like listening to music. See if you can feel the empathy. Let your feelings come out." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

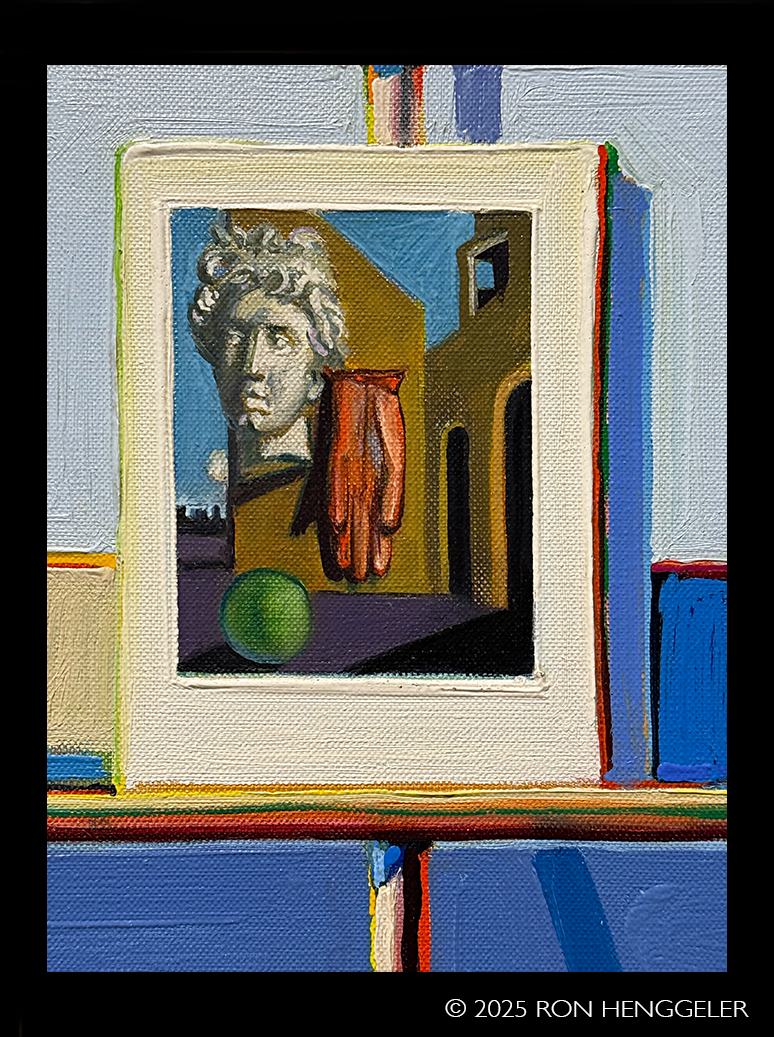

Detail of:

35 Cent Masterworks

1970, 1972 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

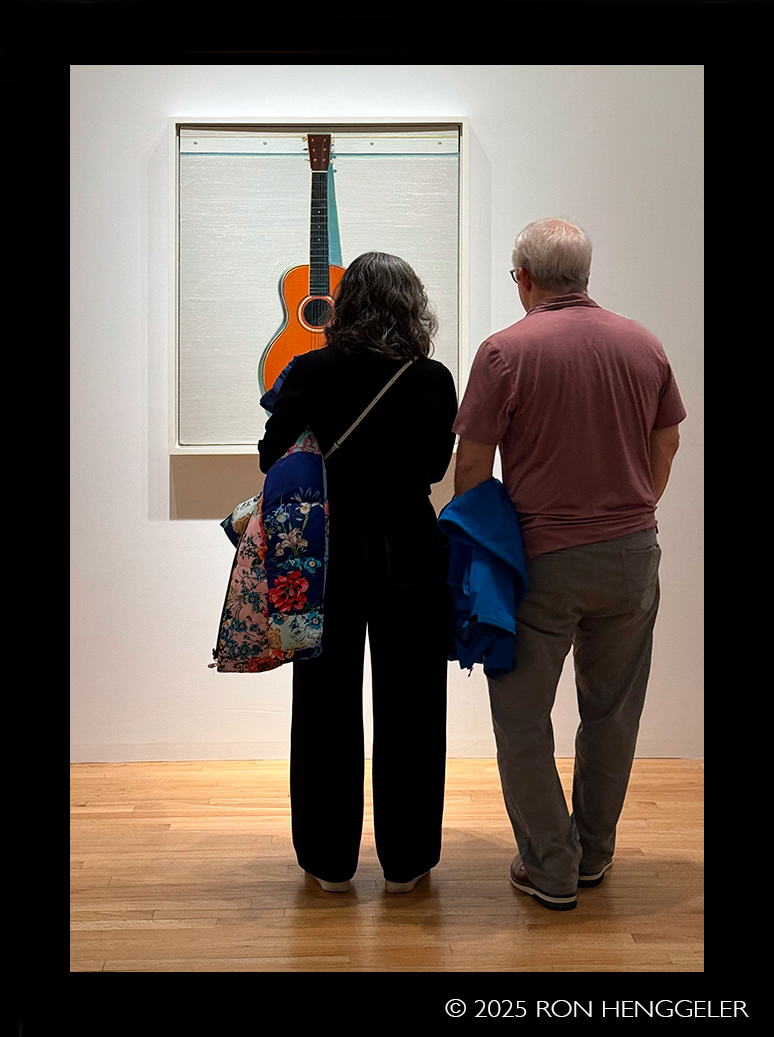

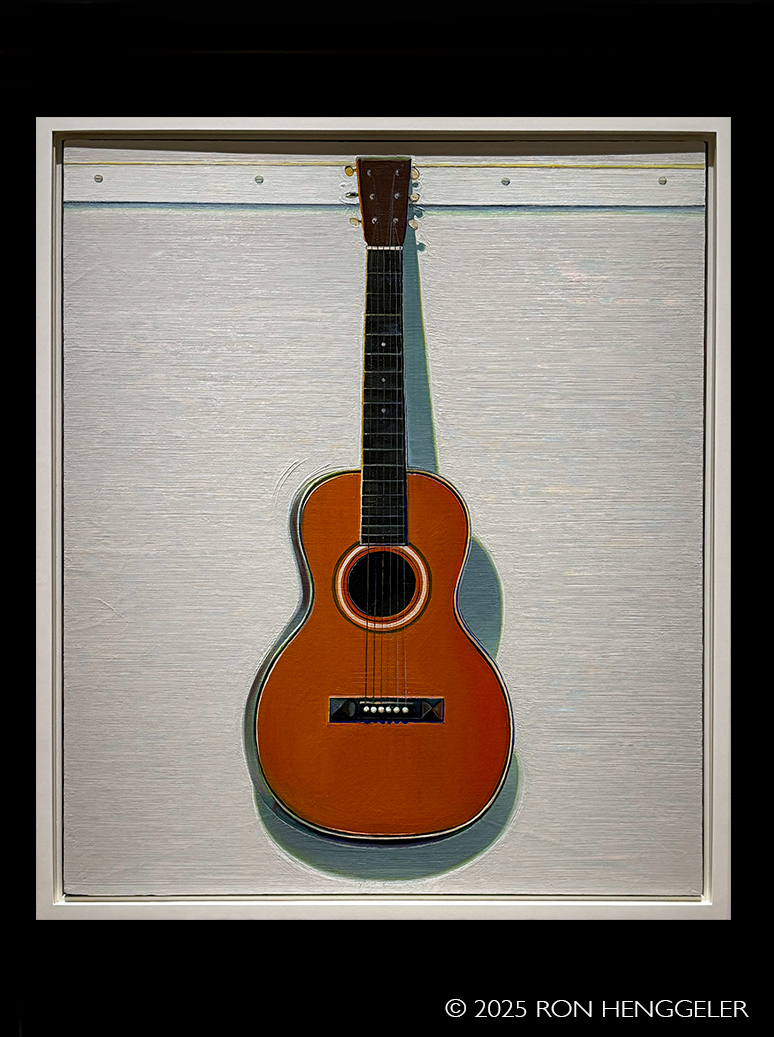

Guitar, 1962, 2002

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's portrait of his Martin guitar subtly evokes the senses of sight, sound, and touch. The instrument originally lacked the horizontal board behind it, thus challenging viewers to decide whether it was a gravity-defying guitar, or an aerial view of it resting on a flat surface. Thiebaud's addition of the horizontal wood board forty years later is equally puzzling, as guitars don't typically include hanging hardware.

Picasso's famous Guitar, created with two-dimensional sheet metal, also plays with our preconceived ideas of how to depict three-dimensional objects.

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

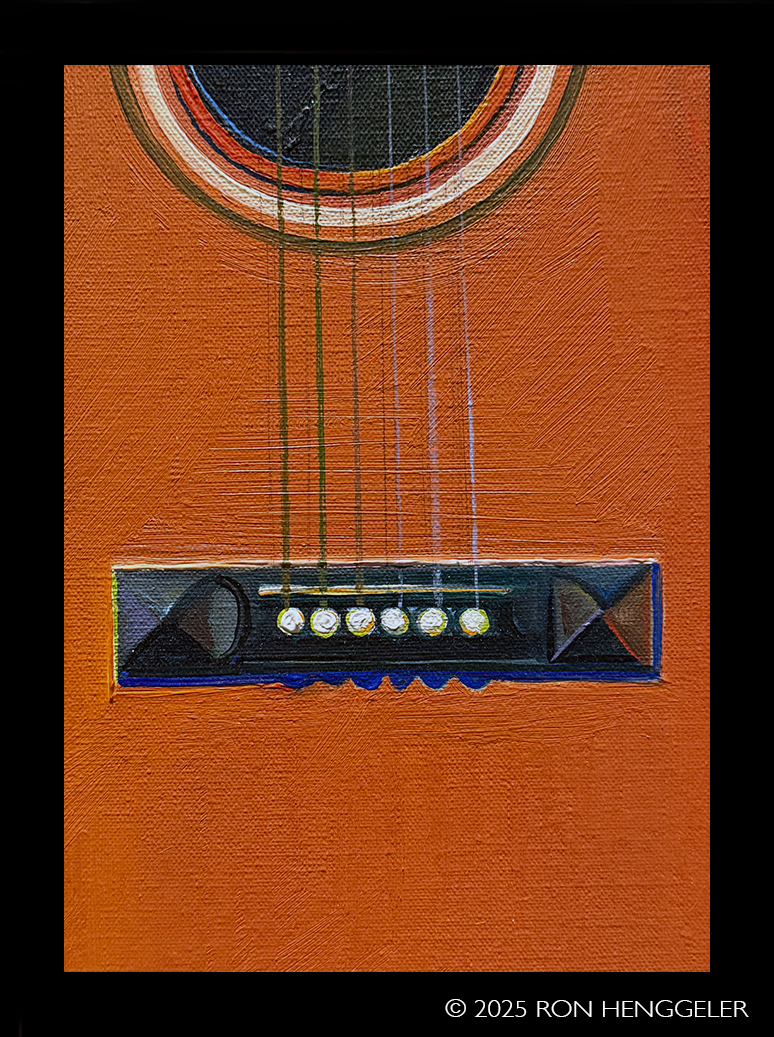

Detail of: Guitar, 1962, 2002

Oil on canvas

"Picasso says it best: 'Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth.' When an artist is closest to rendering the 'real, or the feeling of illusion, it's almost mandatory to juxtapose a disreality-something that does not work at all-to make it seem real."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

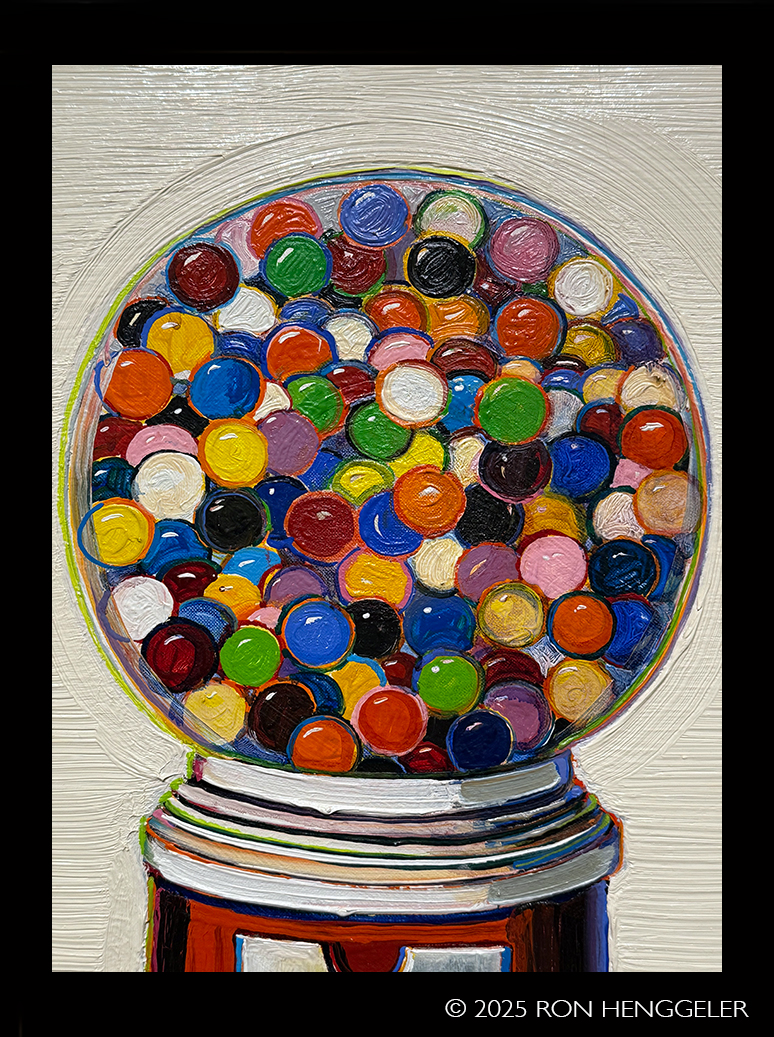

Three Machines, 1963

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's distinctive depictions of American popular culture often reveal larger truths. Gumballs were the most common penny candy-a sort of atomic particle of American consumer culture. They also represent, in microcosm, the cycle of American consumerism, which spans from an imagined ideal, to the pleasure of posses-sion, to a state of diminishing returns, and finally to a sense of loss-until this cycle begins again. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

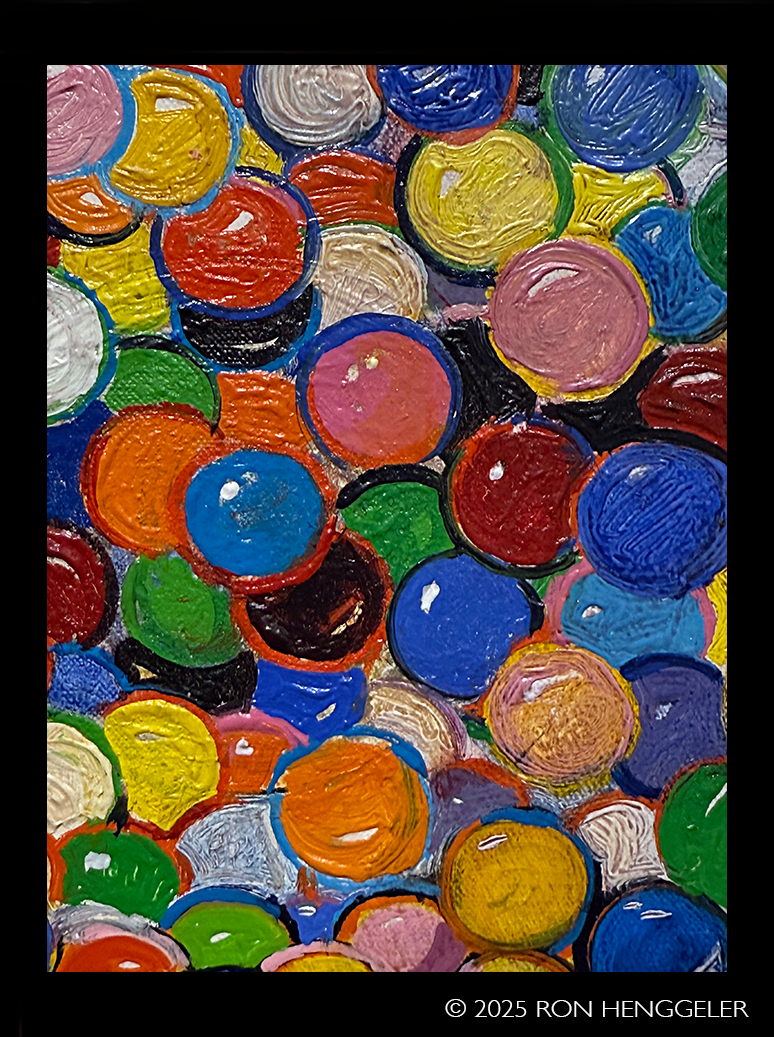

Detail of: Three Machines, 1963

Oil on canvas

Describing the origins of his signature food subjects, Thiebaud cited Loren Malver's remarkable painting Penny Candy Vendors (1940), observing:

"Well, I must have seen things that represented what it was possible to do. I remember later on seeing a painting by a wonderful woman painter, Loren Maclver, a gumball machine. I didn't see it until years later, but it's in the Metropolitan Museum." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Three Machines, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Sucker Tree, 1962

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's tapering Sucker Tree visually echoes the French artist Marcel Duchamp's famous Bottle Dryer and, more importantly, their shared belief that even the most ordinary objects could be transformed into art.

Art Expressions LLC |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Sucker Tree, 1962

Oil on canvas

"I try to find things to paint which I feel have been over-looked. Maybe a lollipop tree has not seemed like a thing worth painting because of its banal references... more likely it has previously been automatically rejected because it is not common enough. We do not wish it to be the object which essentializes our time. Each era produces its own still life."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Confections, 1962

Oil on canvas

Confections pays direct tribute to Giorgio Morandi's

Still Life of 1941. Thiebaud noted, "I have taken Morandi paintings and worked with them directly next to myown paintings to try and make mine look more like his."

The human associations evoked by both artists' still-life objects subtly suggest narratives of inclusion and isolation.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art,

Gift of Byron R. Meyer, 2014.343 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Confections, 1962

Oil on canvas

"On [Morandi's] simple 'stages' objects are cast in various roles. Tableaux and friezes in scene after scene infer arresting little dramas.... What a rich array of evocative powers through such seemingly simple means!"

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Confections, 1962

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Electric Chair, 1957

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's shift to his signature mature style was accelerated by his transformative 1956-1957 trip to New York City. Electric Chair is an atypically serious subject, likely inspired by the bold brushstrokes in Franz Kline's The Bridge of 1955, which Thiebaud would have seen during his visit to the artist's New York studio. This painting is one of the earliest in which Thiebaud attempts to reinterpret an abstract painting in representational form.

Thiebaud was struck by the contrast between the Abstract Expressionist artists' radical works and their interest in art history:

"It was just shocking to hear someone like Franz Kline talking about Vermeer, until you thought about his work.And it was shocking to know how much de Kooning liked Fairfield Porter, for instance. It was interesting to hear Barnett Newman extoll and be so ecstatic over the Mona Lisa, and what he would say about it!"

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC,

Bequest of Edith S. and Arthur J. Levin, 2005.5.69 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Black Shoes, 2018

Oil on board

Inspired by Vincent van Gogh's paintings of his own shoes, Thiebaud created a series of shoe portraits, ranging from ordinary work shoes to these more expensive models.

These shoes served as stand-ins for the artist's personal taste and, over time, as historical artifacts of their respec-tive eras. However, they retain their original associations with Van Gogh's moving shoe paintings, which have come to symbolize the Dutch artist's humble life and financial struggles.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Black Shoes, 2018

Oil on board

"It seems to me that's part of the way in which the tradition of painting plays out. You find enough of a variant to say, for instance, that's a [Vincent] van Gogh species-though it comes from [Adolphe] Monticelli, and [Camille] Pissarro, and [Honoré] Daumier, etc., etc. It has finally eluded enough of that characterization of form to become its own species.Part of that is my search as well."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Trucker's Supper, 1961

Oil on canvas

Trucker's Supper owes a clear compositional debt to Richard Diebenkorn artworks like this Untitled still life— a painting that Thiebaud later acquired for his personal collection. Both works show a general awareness of Mark Rothko's horizontal color fields, a specific use of three diagonal bands, and an arrangement of objects that seem to float in an ambiguous space.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Trucker's Supper, 1961

Oil on canvas

Describing this Diebenkorn painting, Thiebaud observed: "One of the enduring aspects of the painting is its freshness, directness. It's not fussed with or modified.... The nice thing about Dick's paintings is that they are quite equivocal. We are partially responsible for finishing and identifying things, participating in the painting itself by using our own sense of imagination and looking slowly. We are always asking the question: What is that, or how is it functioning?' He leaves that nice incompleteness always there." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Trucker's Supper, 1961

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Gun, 1970-1971

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's Gun appears to draw inspiration from American trompe l'oeil (fool-the-eye) still-life paintings such as William Michael Harnett's The Faithful Colt. Unlike Harnett's real revolver, Thiebaud's gun is almost certainly a toy cap pistol and is rendered receding into space, which requires more skill than depicting the silhouette of a revolver lying flat against a wall or door. However, Thiebaud shared Harnett's interest in introducing common objects into the realm of fine art. Harnett's painting helped mythologize the Colt revolver and its use in the western expansion of the United States, while Thiebaud's cap pistol recalls the influence of this mythmaking on children through movie and television Westerns and their associated toys.

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

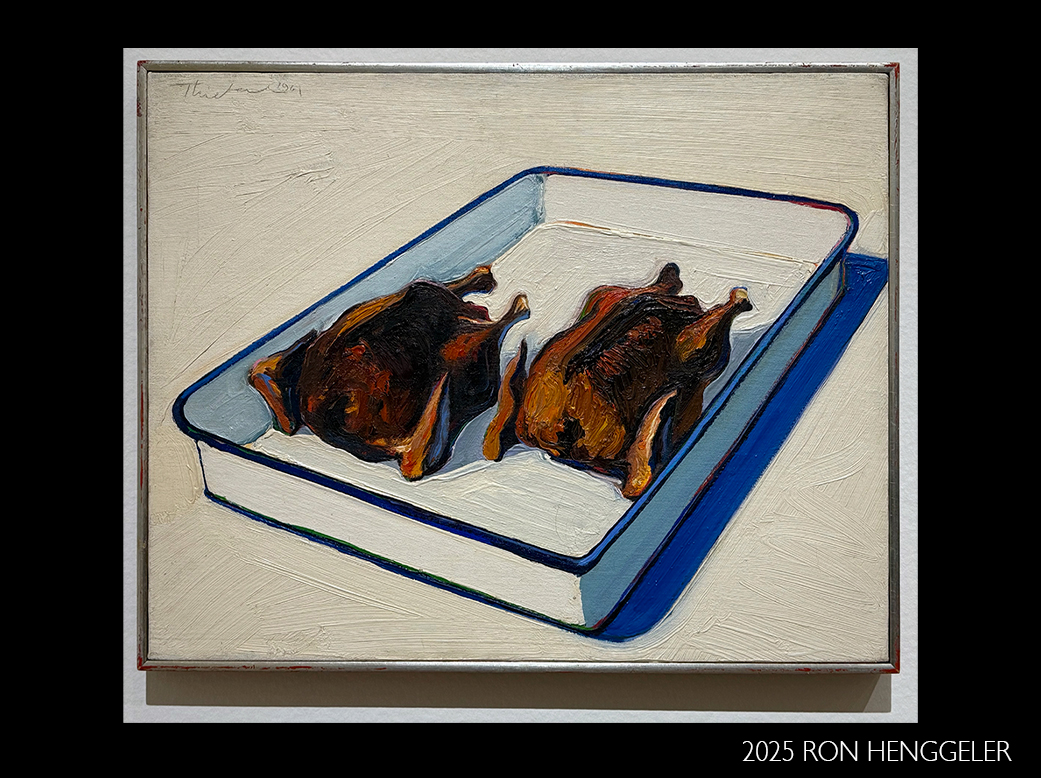

Bar-B-Qued Chickens, 1961

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's Bar-B-Qued Chickens draws upon a long tradition of still-life paintings featuring dead birds. However, its raw sensibility is derived from Chaim Soutine's uncompromising depiction of lifeless animals that have been sacrificed for human consumption. Thiebaud described his own painting of two charred chickens as "a kind of murder" and "a metaphor of tragedy."

"Well, there are great lessons and great influences and I've actually stolen things from [contemporary artists]. I try to do what they do. De Kooning in terms of his premier coup bravura painting. Thats a long, long tradition starting with Velazquez, through Manet to Soutine, De Kooning, where they have to juggle simultaneously several perceptual images at once to make a coalescent form, which encases and combines those perceptual nuances all at once. That's Why they make so many failures of course."

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

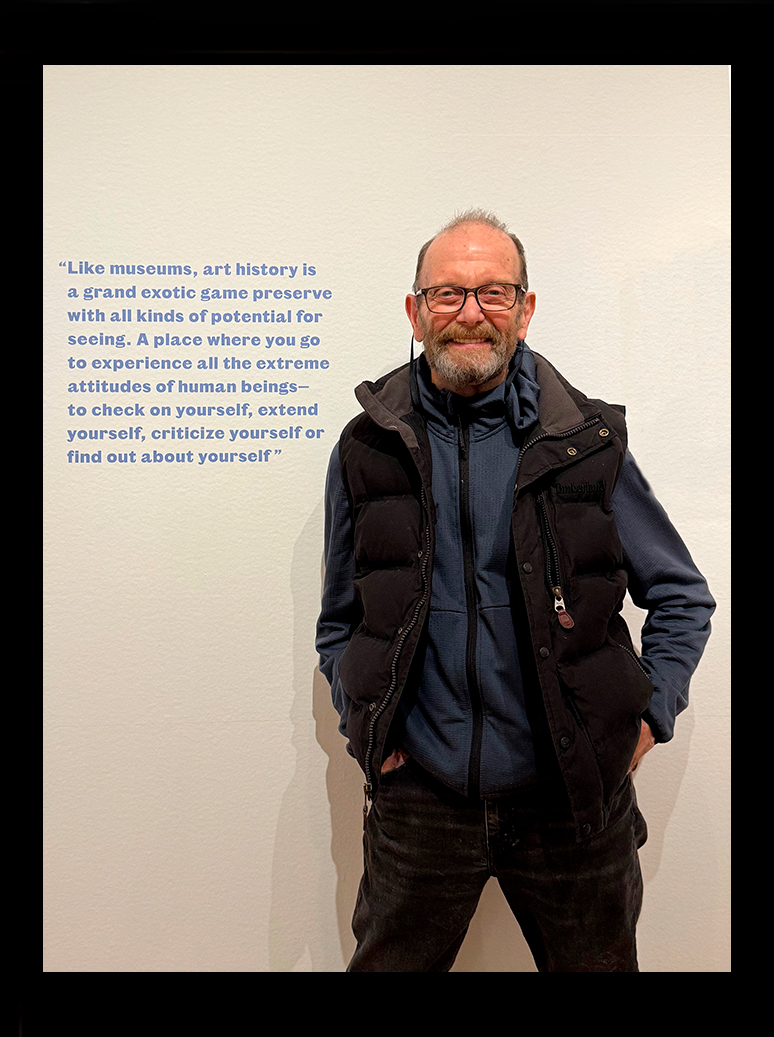

Photo by Stephen Crow

"Like museums, art history is a grand exotic game preserve with all kinds of potential for seeing. A place where you go to experience all the extreme attitudes of human beings-to check on yourself, extend yourself, criticize yourself or find out about yourself."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Stephen Crow |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Woman in Tub, 1965

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's Woman in Tub references Jacques-Louis David's Marat Assassinated, which depicts Jean-Paul Marat, a major figure in the French Revolution of 1789, who was murdered in his bathtub. The open-eyed subject of Woman in Tub appears to be alive, if somewhat dazed, but her resting head and blank expression suggest boredom or exhaustion. When asked if he had David's painting in mind while painting his wife, Betty Jean, Thiebaud replied:

"Yes, I did. It occurred to me, I think, in the process of working on it. I'm very influenced by the tradition of painting and not at all self-conscious about identifying my influences such as that or any other. I think sometimes it's very conscious at the beginning, and sometimes it occurs to me in the middle or sometimes when I'm through with it."

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

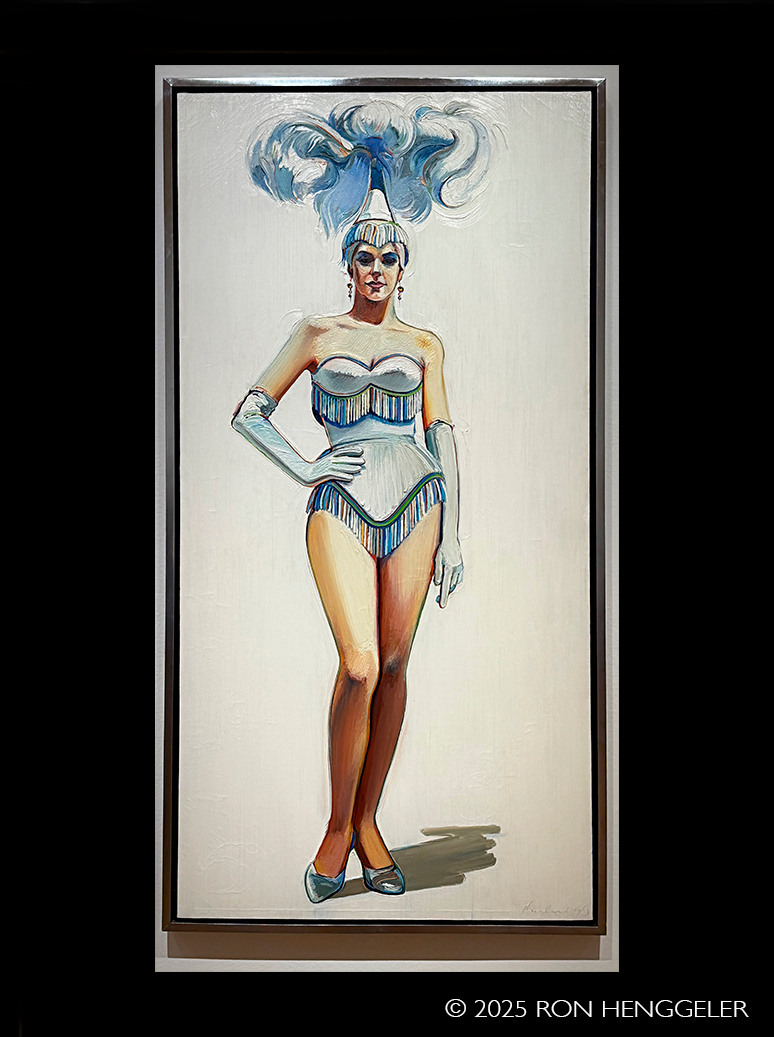

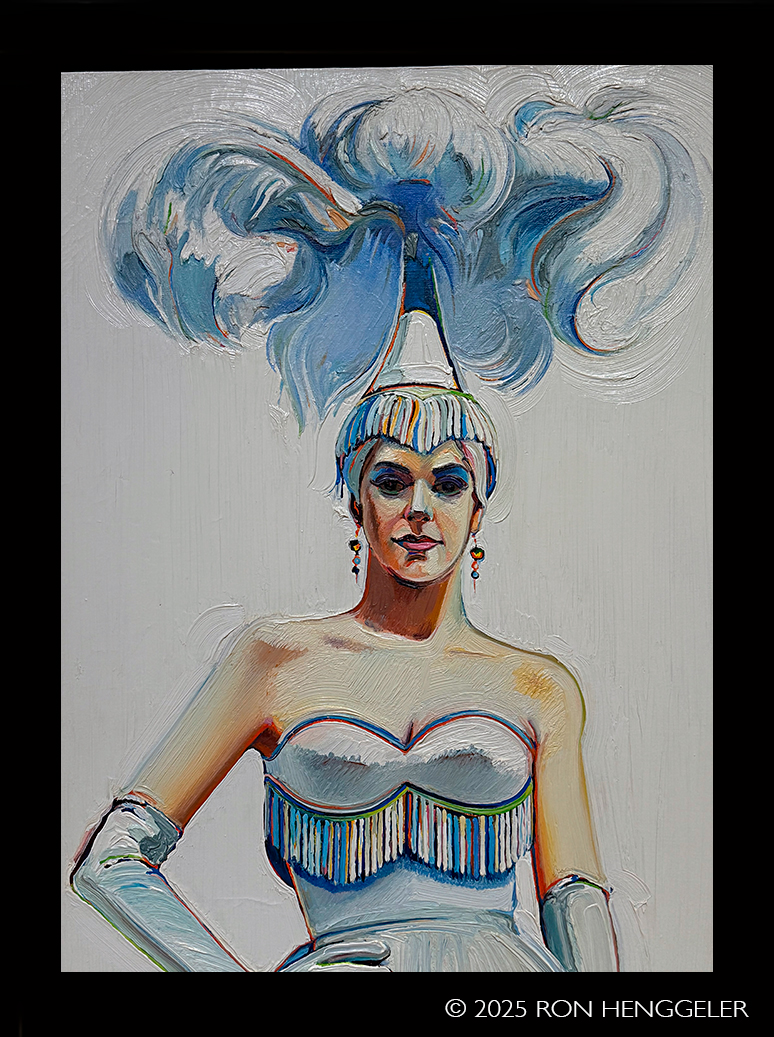

Revue Girl, 1963

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud greatly admired Walt Kuhn, who played an important role in sustaining the figurative tradition in American art during the rise of abstract art. Thiebaud's copy of Kuhn's Clown with White Tie (1946) is on view in the first gallery of this exhibition, and he noted that"Walt Kuhn is a big hero in terms of what he could capture."

The flattened and abstracted elements of Kuhn's circus and vaudeville figure paintings influenced the evolution of Thiebaud's own paintings. The revue girl, wearing a fringed costume and a headdress adorned with flamboyant feathers, poses confidently, but her tiny cartoon shadow renders her more like a paper doll.

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

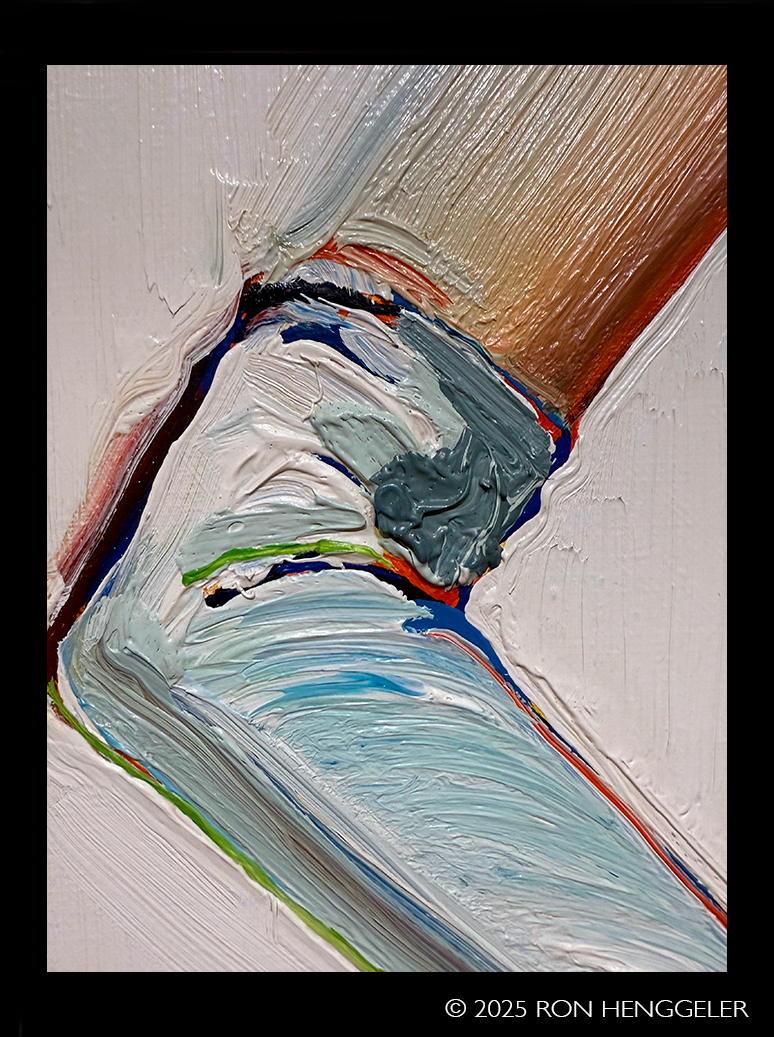

Detail of: Revue Girl, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

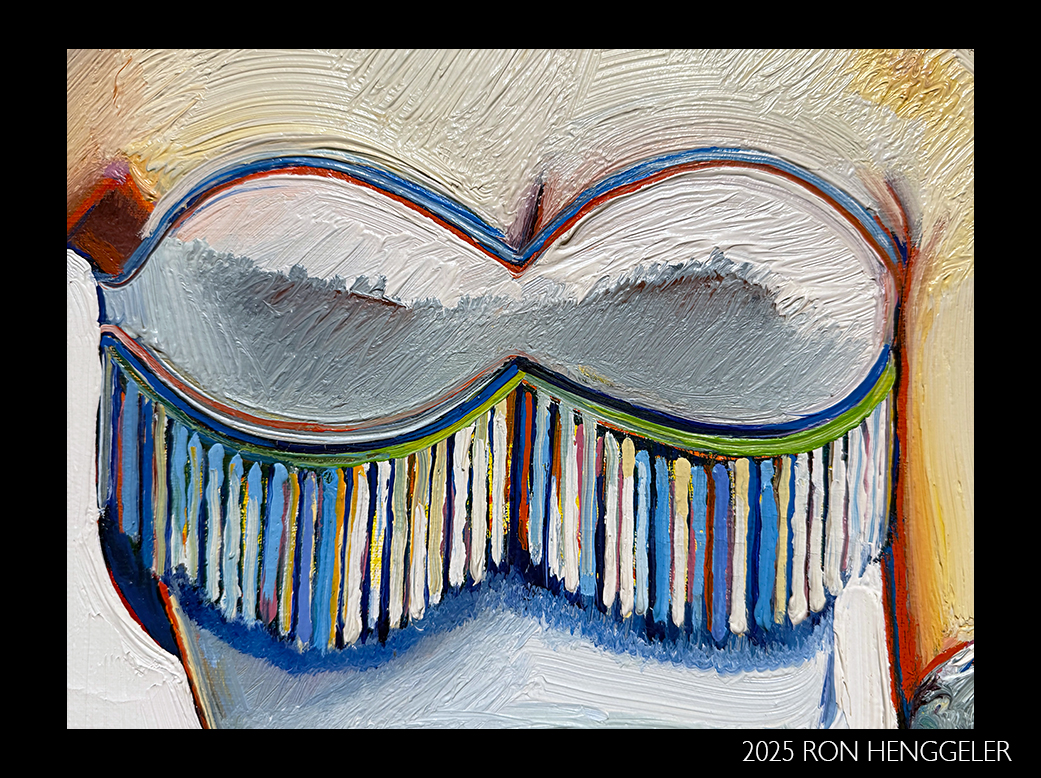

Detail of: Revue Girl, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Revue Girl, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

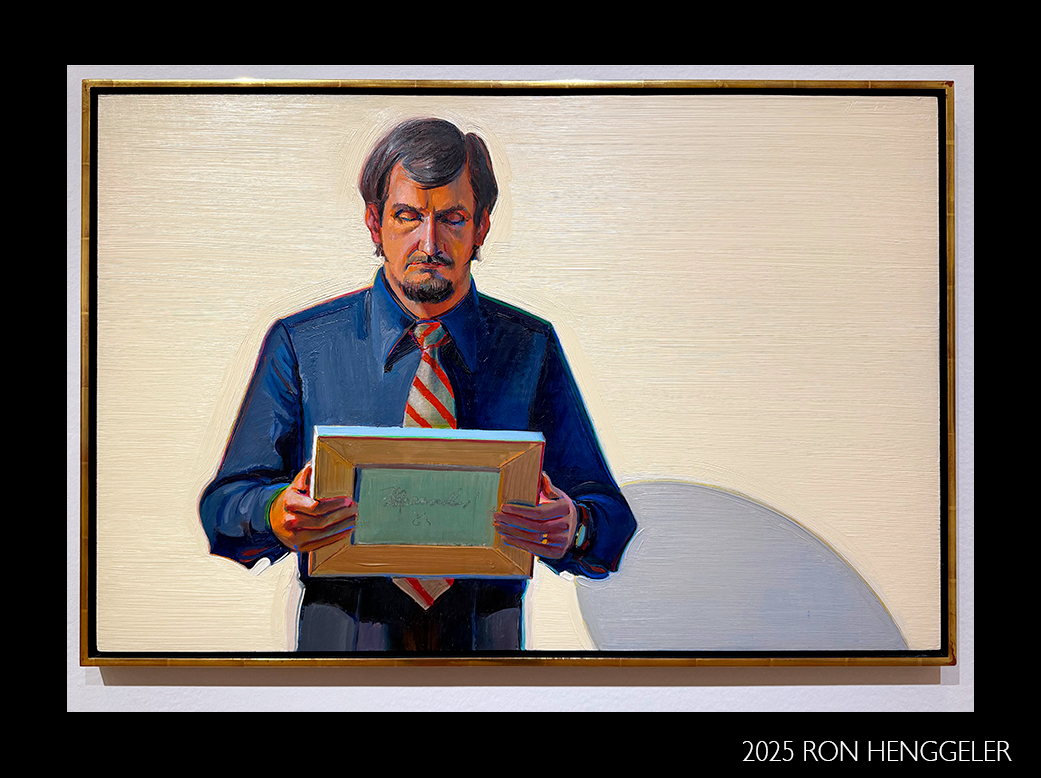

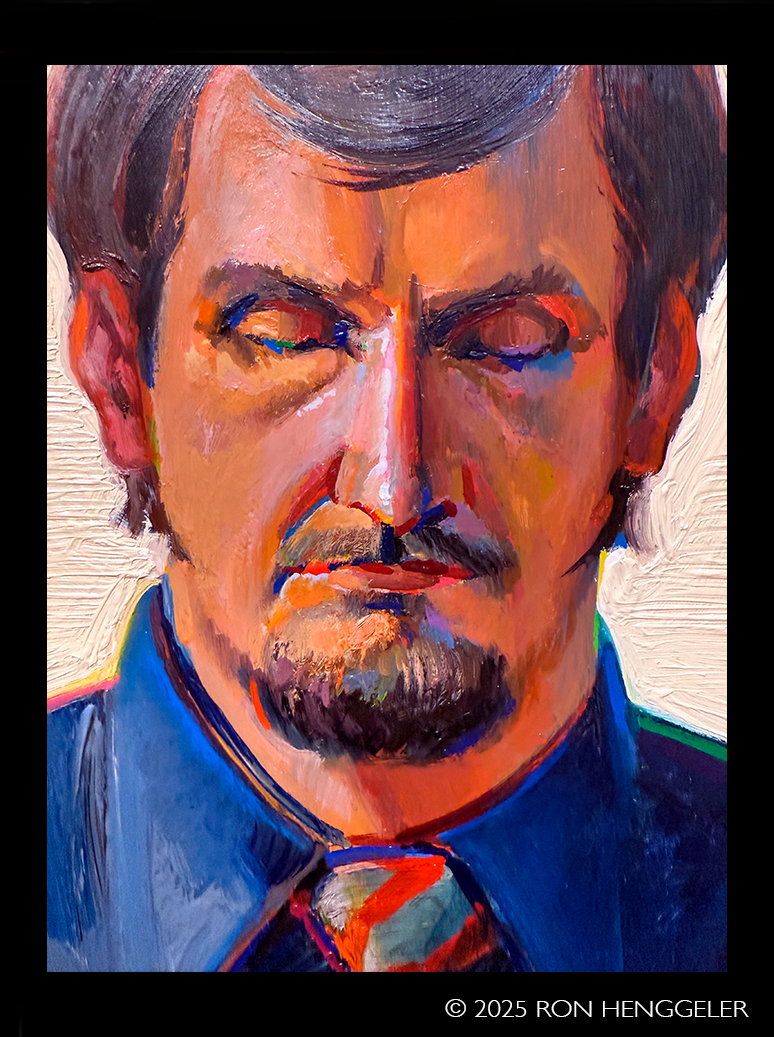

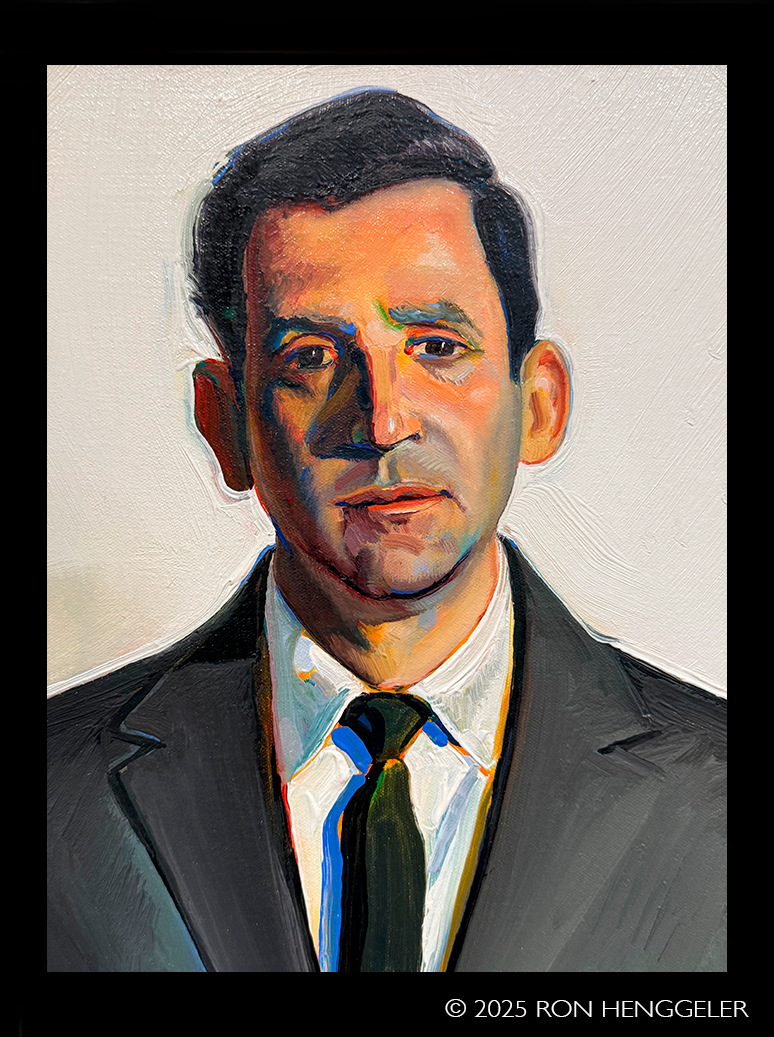

The Art Historian (G.C.), 1971

Oil on board

Honoré Daumier's Advice to a Young Artist, and Thiebaud's copy of this painting, on view in the first gallery of this exhibition, both served as sources of inspiration for The Art Historian (G.C.), which depicts professor and curator Gene Cooper, who was organizing a Thiebaud exhibition. Daumier's painting captures the uneven power dynamic between an inexperienced and impressionable young artist and an established and knowledgeable older art-world figure.

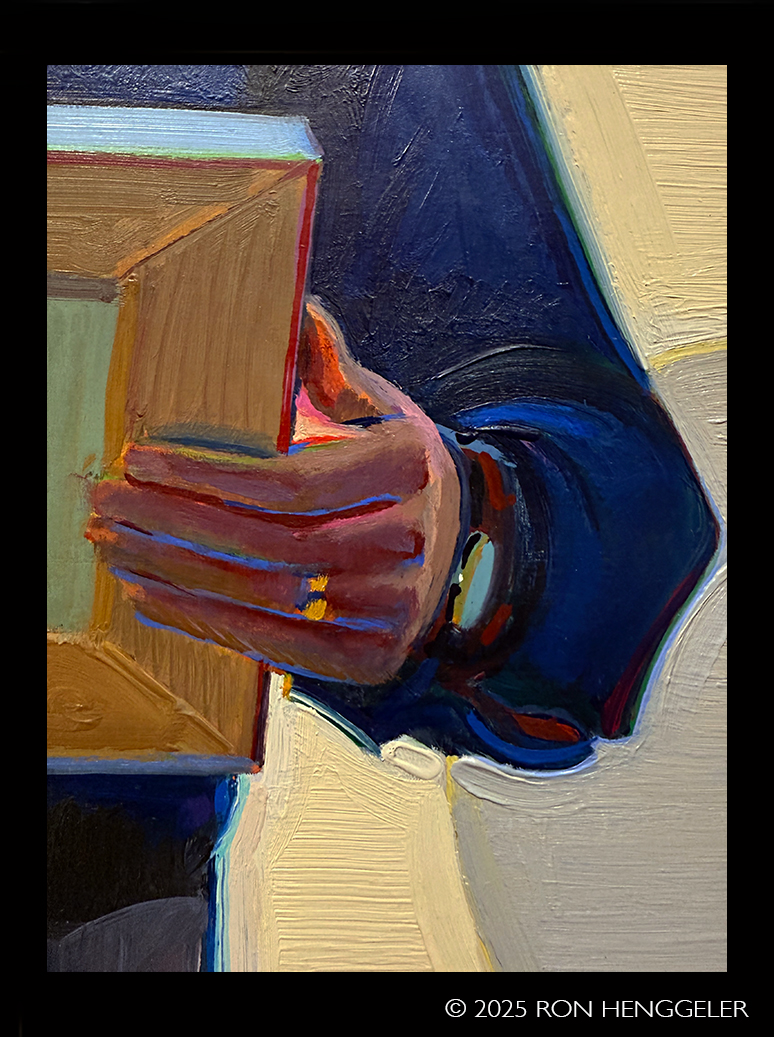

Cooper holds a small painting whose surface and subject are concealed from the viewer, although the back of the canvas is inscribed "Morandi / '63" in honor of one of Thiebaud's heroes-Italian artist Giorgio Morandi. As a professor, curator, and informal Thiebaud art student, Cooper would have played roles comparable to both subjects in Daumier's painting. Thiebaud admired Daumier as a caricaturist who captured the human condition, noting, "My work is closer to caricature than to photo realism."

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: The Art Historian (G.C.), 1971

Oil on board |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: The Art Historian (G.C.), 1971

Oil on board |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

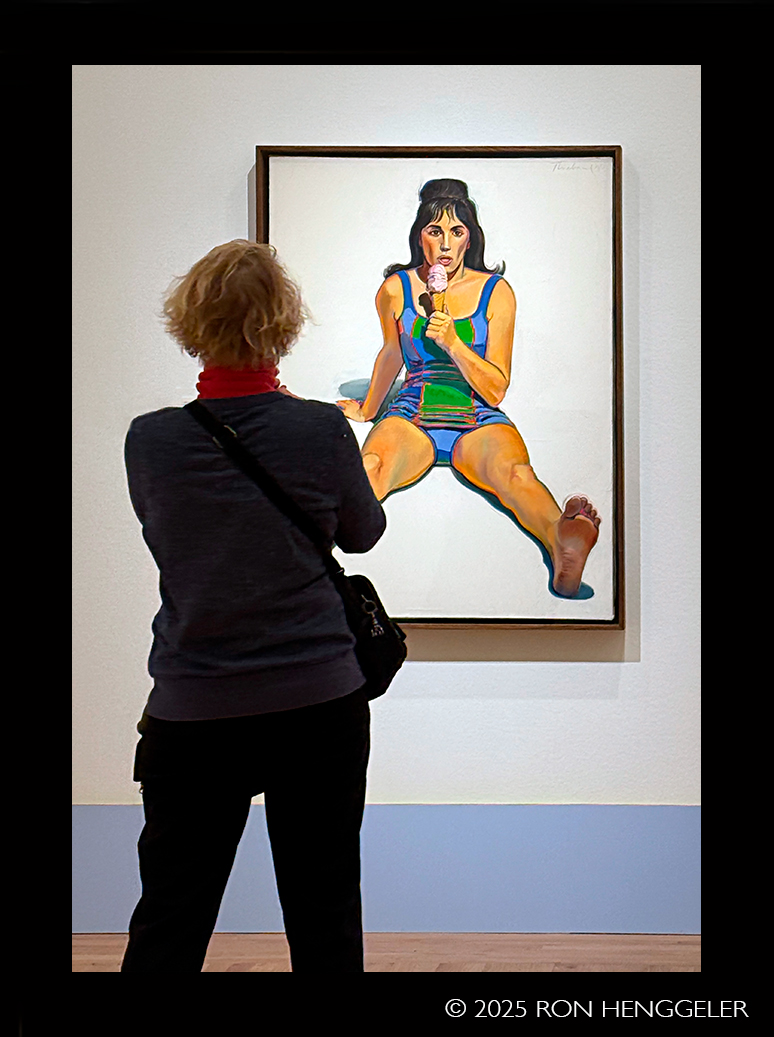

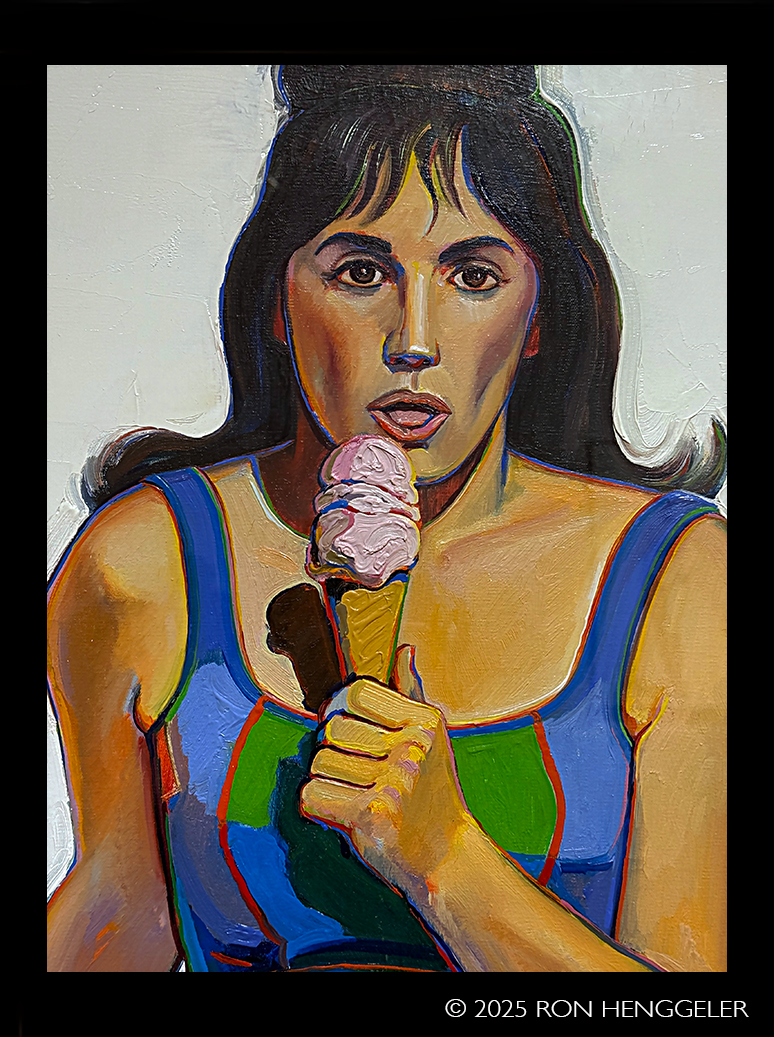

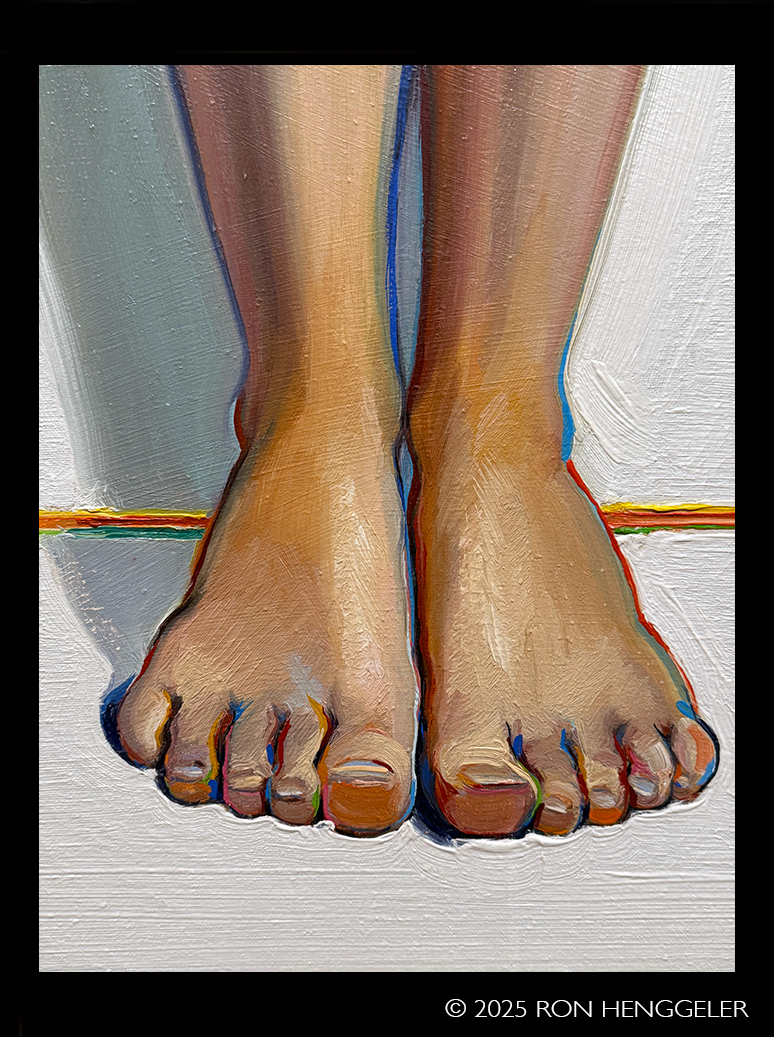

Girl with Ice Cream Cone, 1963

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's portrait of his wife, Betty Jean, posed holding an ice cream cone, emulates the radical perspective of the human figure in Andrea Mategna's Lamentation Over the Dead Christ. Both works accentuate the prominent bare feet, and a foreshortened view between their legs.

Commenting on Mantegna's painting, Thiebaud said: "I love that painting.... Foreshortening, the caricature that he came up with ... absolutely a delight. I mean it's as much a cartoon as it is a couple of feet and I love that— that's the stuff that really attracts me a great deal. So here [in Girl with Ice Cream Cone], you see a little bit of an evidence of that, the difference let's say between those big bare feet sticking in your eye almost, and then the little hand way back in the back with a little blue shadow."

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

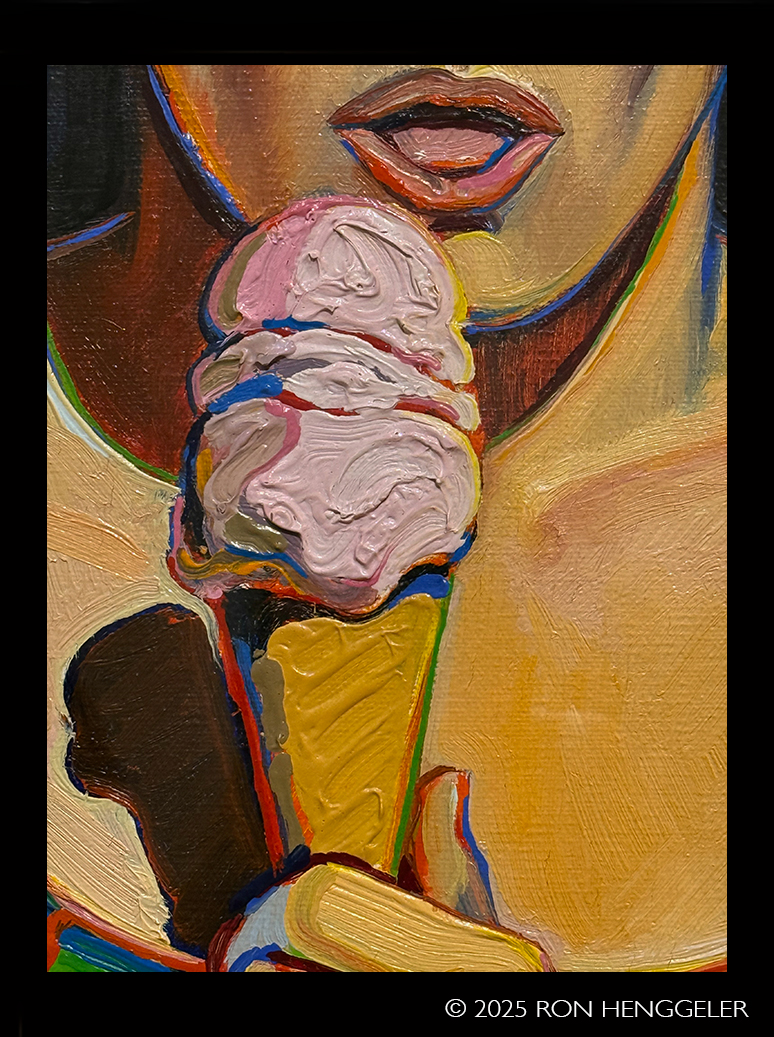

Detail of: Girl with Ice Cream Cone, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Girl with Ice Cream Cone, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Girl with Ice Cream Cone, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

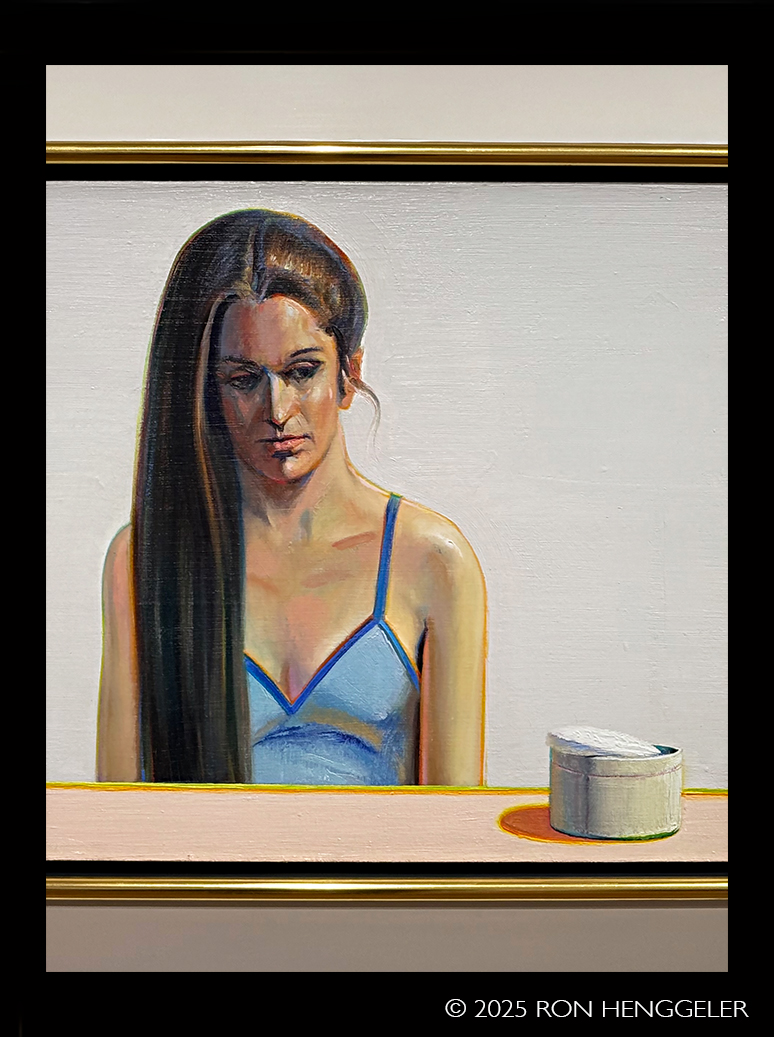

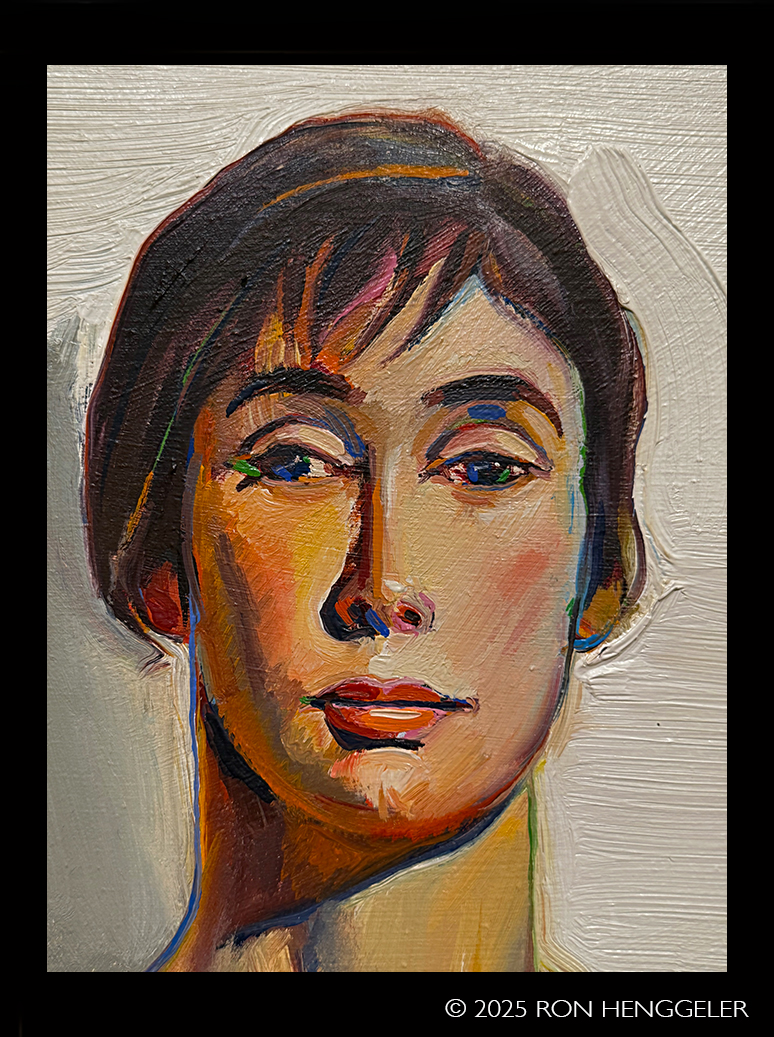

Make Up Girl, 1982

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Make Up Girl, 1982

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud borrowed the blade-like hair in Henri Matisse's

The Italian Woman for his Make Up Girl. Thiebaud's repre-sentational style helps distract the viewer's attention from slightly surreal elements, such as the left arm that resem-bles a cylindrical pipe more than actual human anatomy.

"Matisse's line is never just a one-dimensional outline.

It is partly a sculptural line, and throughout his many periods he extends it to slicing, chopping, hacking, severing, sawing, snipping, nipping, cleaving, slashing, truncating, cropping. These are all ways he has of mod-ifying his forms sculpturally."

The Buck Collection

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Make Up Girl, 1982

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

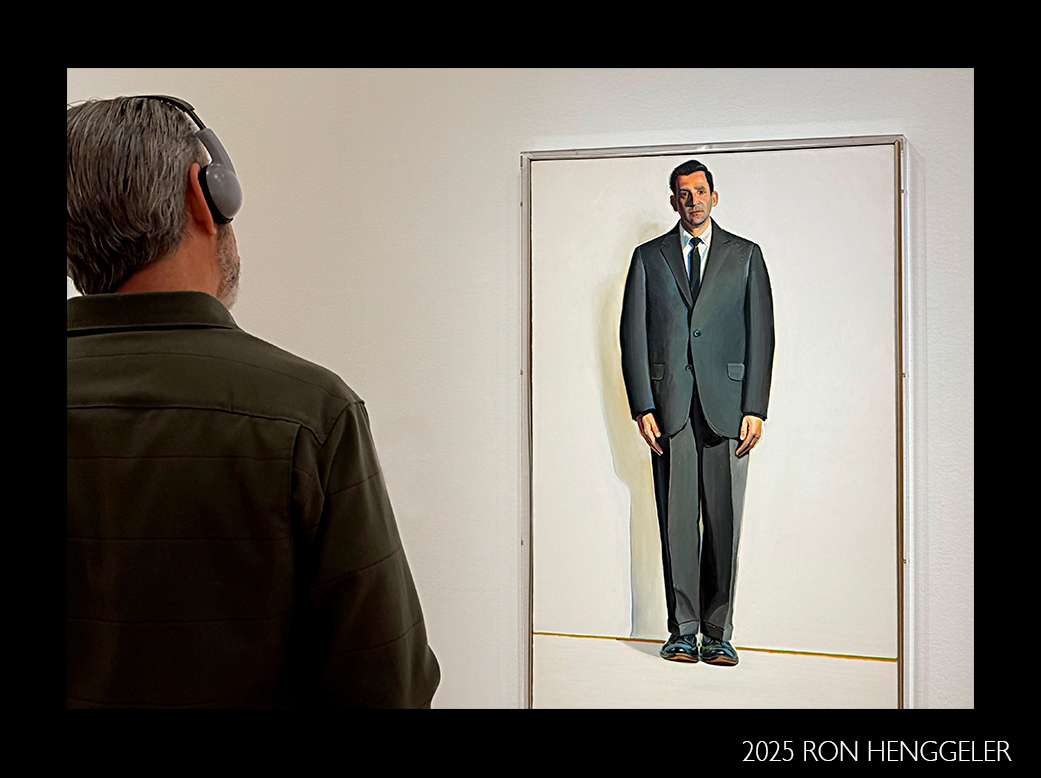

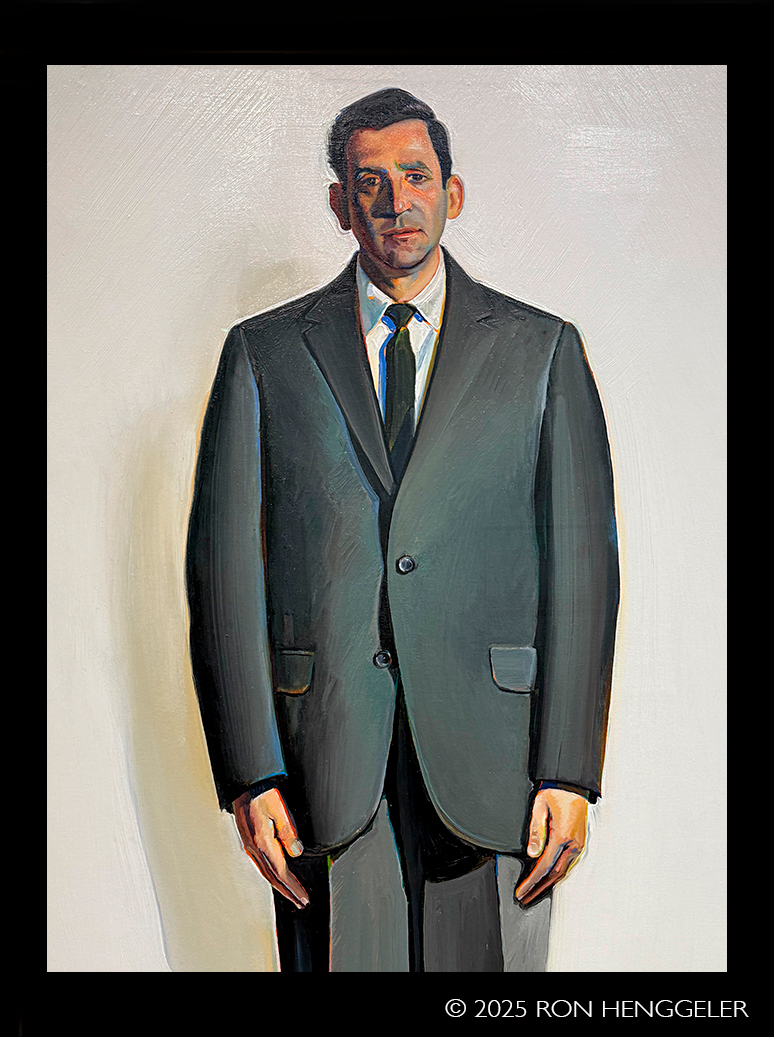

Standing Man, 1964

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Standing Man, 1964

Oil on canvas

The deadpan depiction of Thiebaud's Standing Man recalls both the French artist Jean-Antoine Watteau's Pierrot and the German photographer August Sander's Painter. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

"You know the work of August Sander? I admire his photographs because they're just plain representations of a German cook, a German schoolteacher, a butcher.This is some guy in his ordinary jacket and pants and shoes, or someone sitting in a chair with his back to you.

That's what my paintings were. I'd have people come, usually friends, and ask them to take a stance, turn around, sit down, stand up sit down and read, until I finally get at a position that I would like to, as my wife described it, get them sort of frozen in time."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

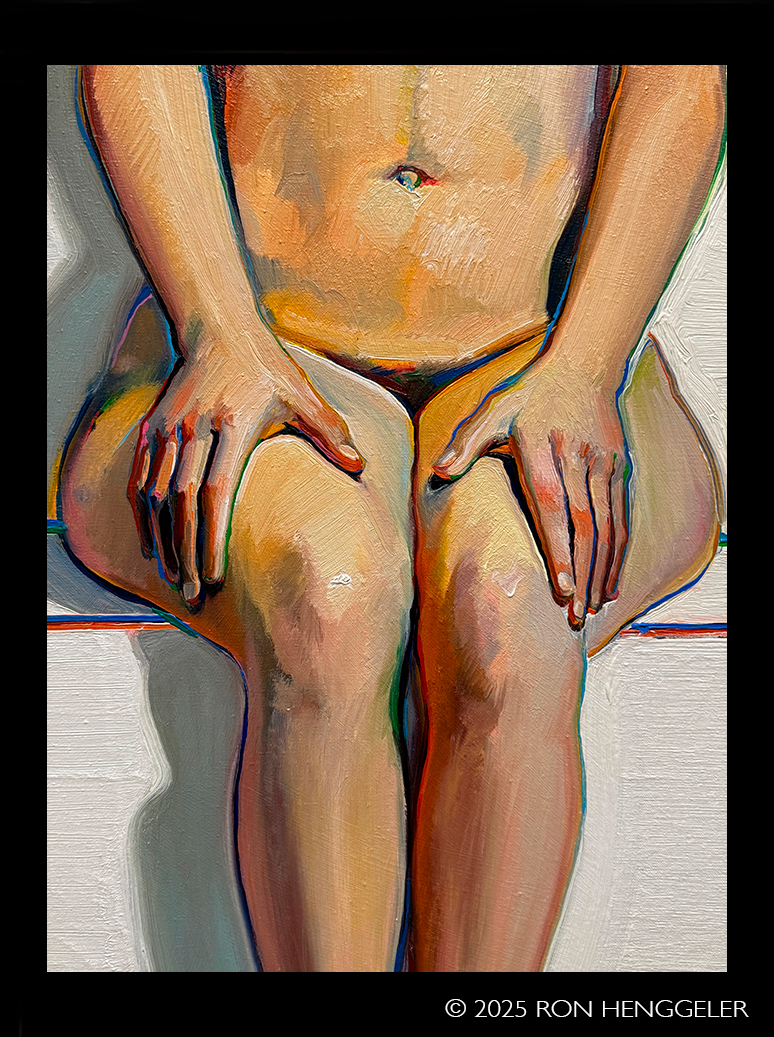

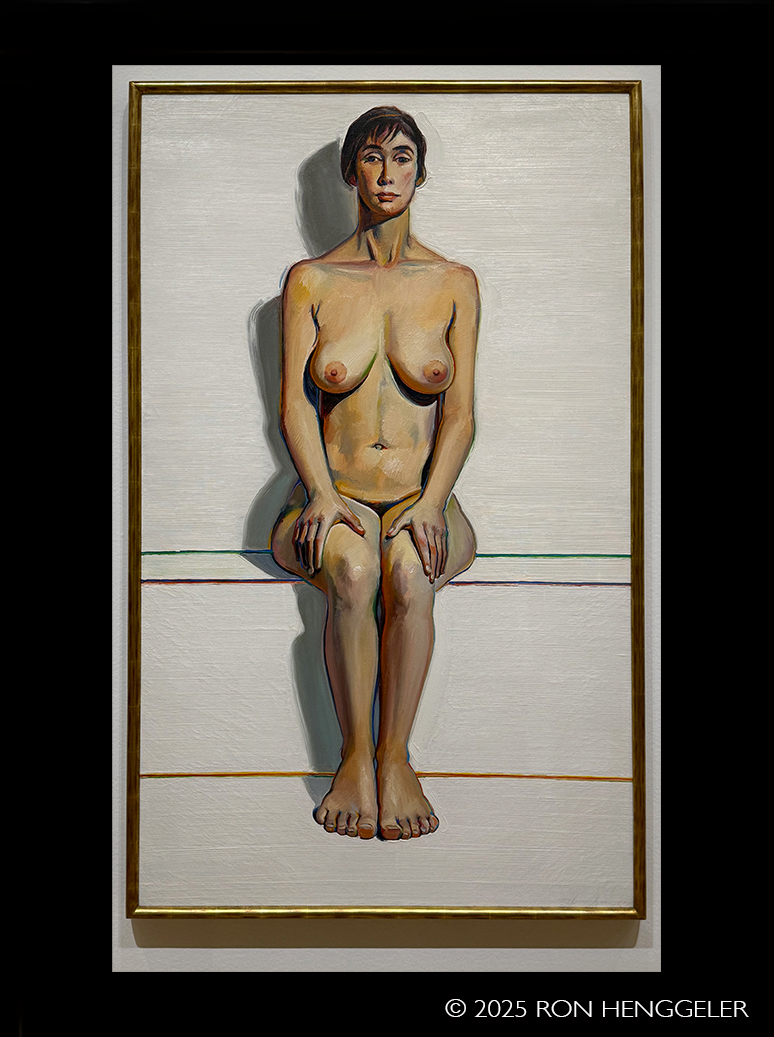

Nude, 1963

Oil on canvas

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch's figure subjects, whose expressive forms mirrored their inner emotional lives, might seem like an unusual source for Thiebaud, who avoided obvious emotions or narratives in his works, stating:

"Purely formal problems have always been what's most important to me, and I try to downplay subject matter because I'm afraid it limits how people think about pictures."

Although Thiebaud's full-length seated Nude borrows its composition from Munch's Puberty, it omits the central narrative of the transition from girlhood to womanhood.

Instead, Thiebaud manipulates the space-and gravity-to suggest that she is magically seated upon two horizontal lines of paint.

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Nude, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Nude, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Nude, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

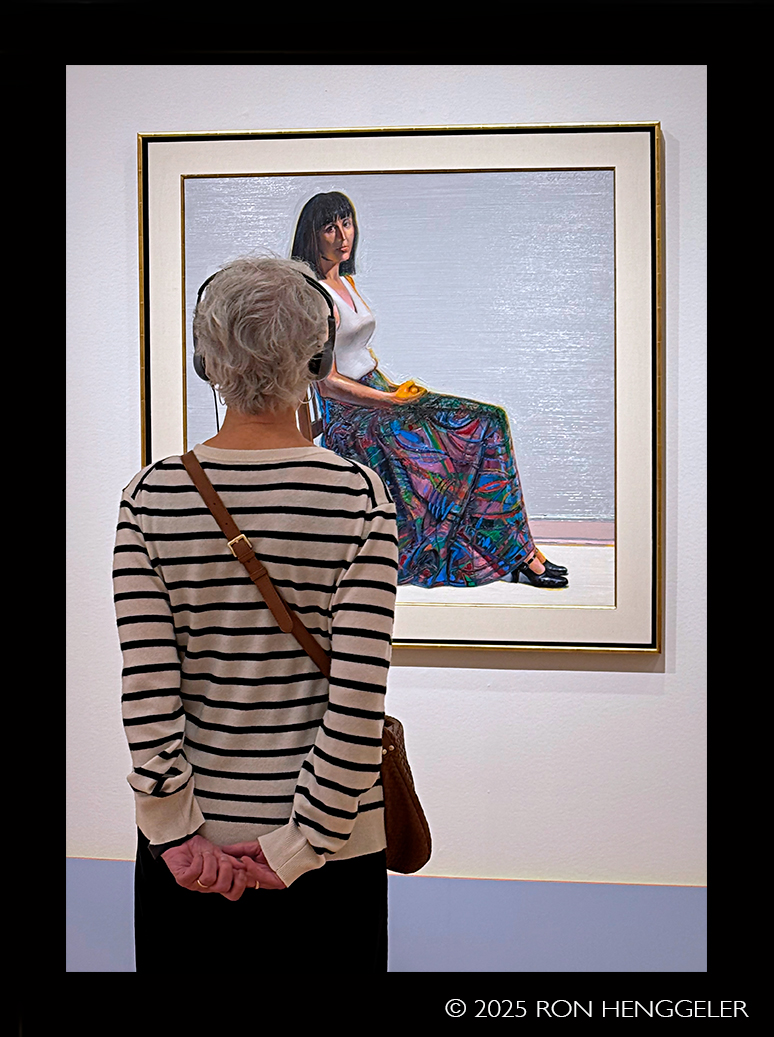

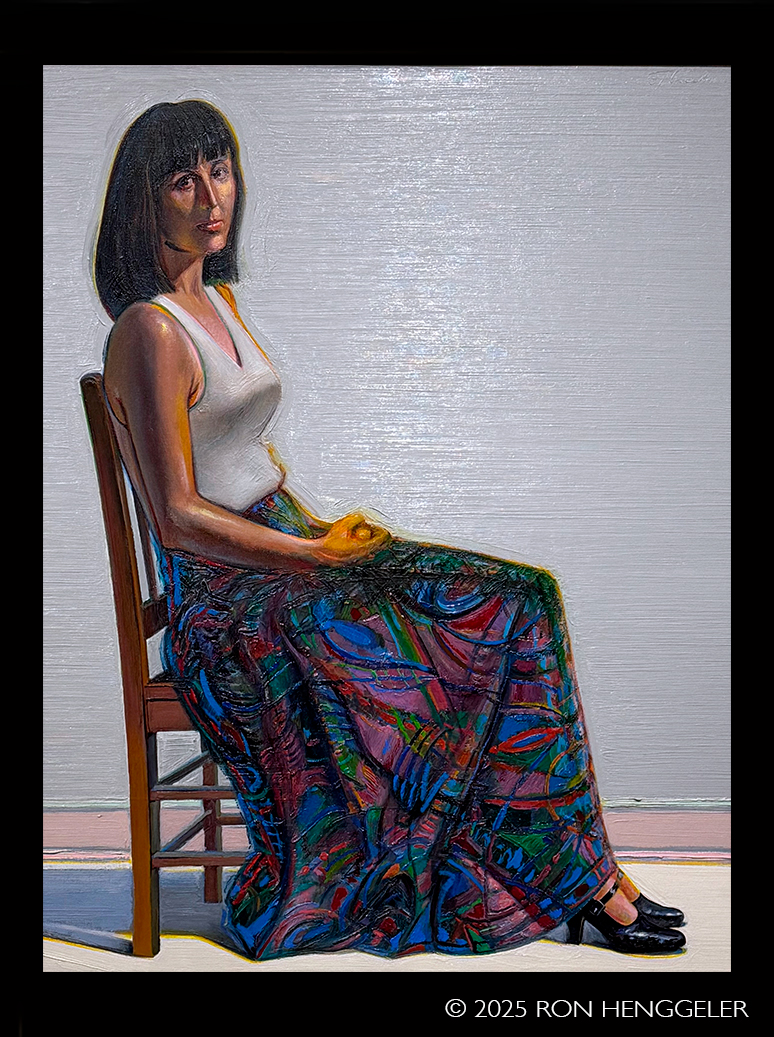

Tapestry Skirt, 1976/1982/2003

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Tapestry Skirt, 1976/1982/2003

Oil on canvas

Tapestry Skirt, a portrait of the artist's wife, Betty Jean, attempts the difficult challenge of reinterpreting one of the most famous American paintings ever created, American artist James McNeil Whistler's Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, popularly known as "Whistler's Mother." Thiebaud's model faces in the opposite direction from Whistler's and also turns her head to acknowledge the viewer. In contrast with Whistler's dark and subtle color harmonies, the focus is on her vividly colored skirt, which resembles the scrambled imagery and colors of a Thiebaud city painting.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

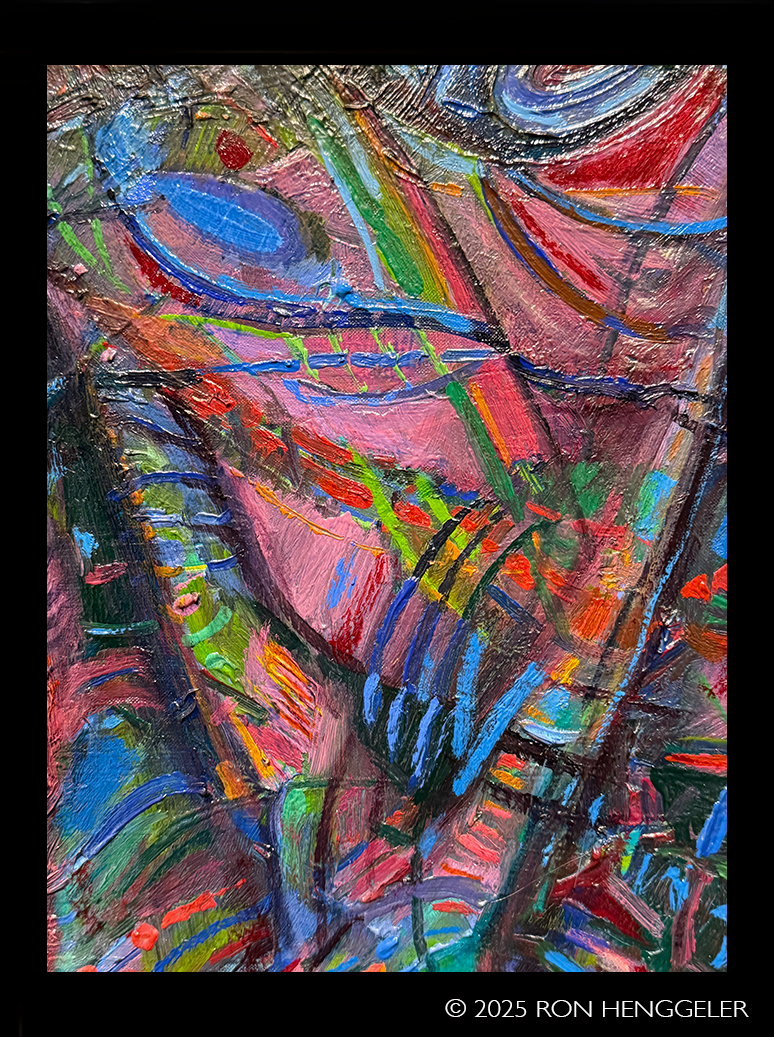

Detail of: Tapestry Skirt, 1976/1982/2003

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Tapestry Skirt, 1976/1982/2003

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

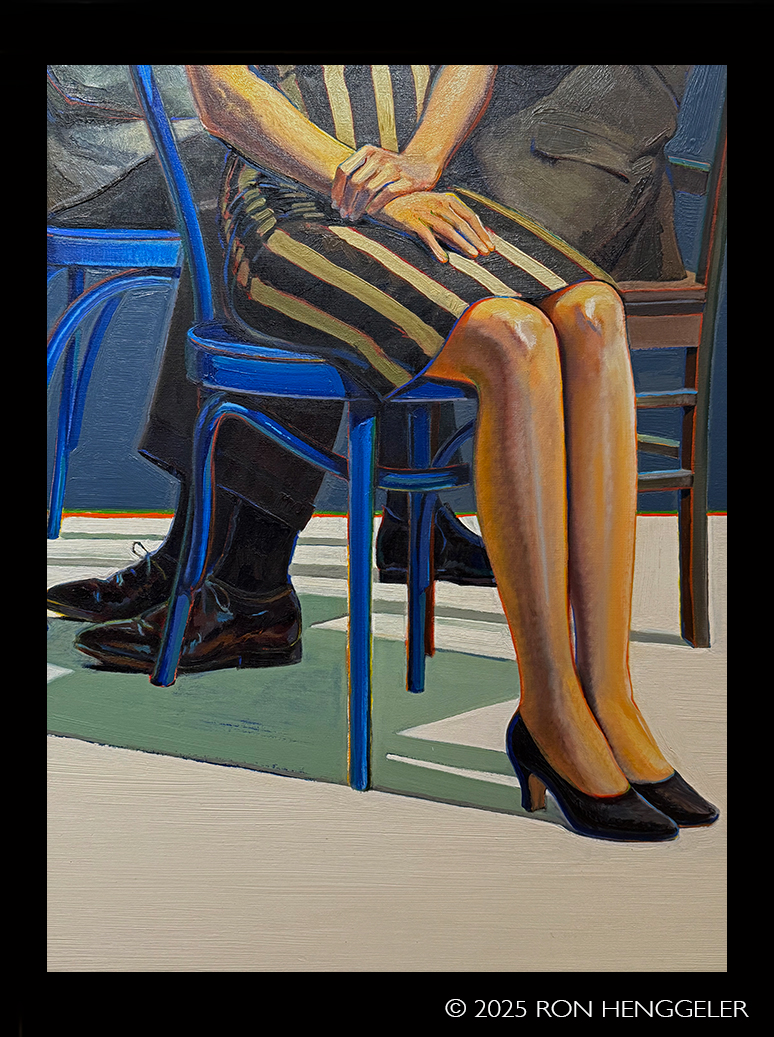

Five Seated Figures, 1965

Oil on canvas

Edgar Degas's group portrait The Bellelli Family, famous for capturing the emotional isolation of the family members, almost certainly was the model for Thiebaud's comparable composition of multiple figures who are closely seated together, yet ignore each other.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Five Seated Figures, 1965

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Five Seated Figures, 1965

Oil on canvas

"So, it's a charge upon a serious painter to make it un-necessarily tough upon himself: find something he can't do. Degas pushing six or seven figures to the right of the canvas and trying to balance it with a watering can, or some crazy thing like that. So, you set for yourself a prob-lem, like figures who come and sit, mostly friends, and they'll sit for hour after hour after hour, and theyll start out with a perky look, wet lips, and so on, and slowly this mask develops. And it's that kind of expressionlessness which is the problem, to try still, in spite of that, to turn the figure into some kind of animated object."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Five Seated Figures, 1965

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Five Seated Figures, 1965

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

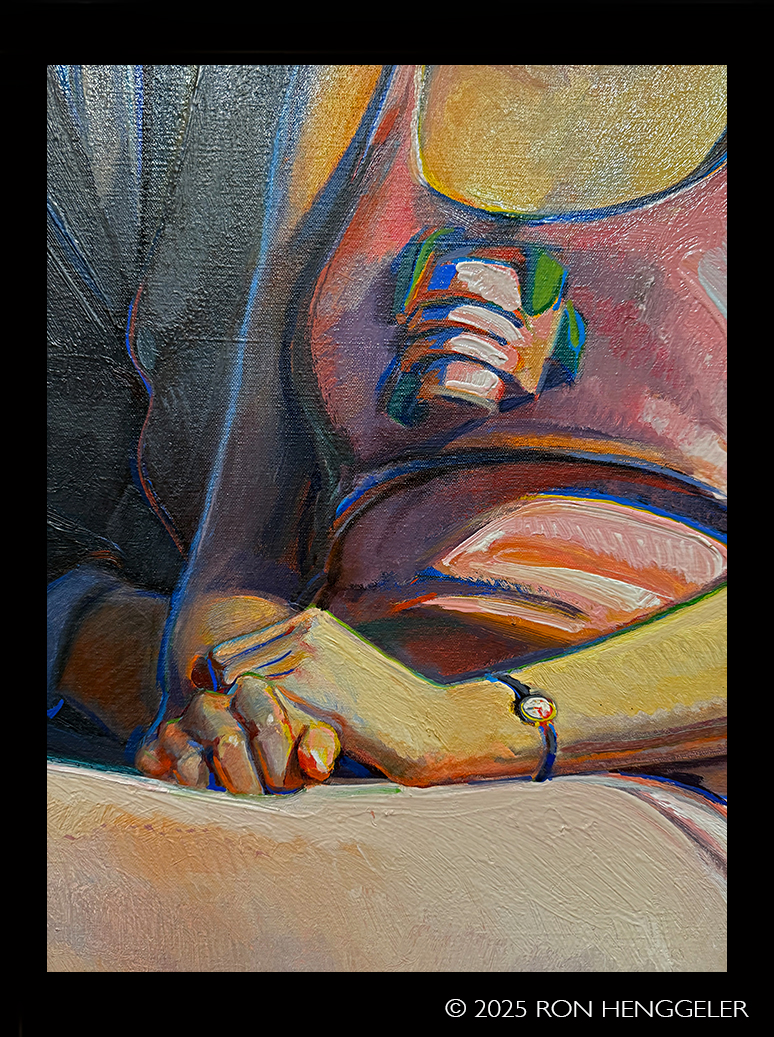

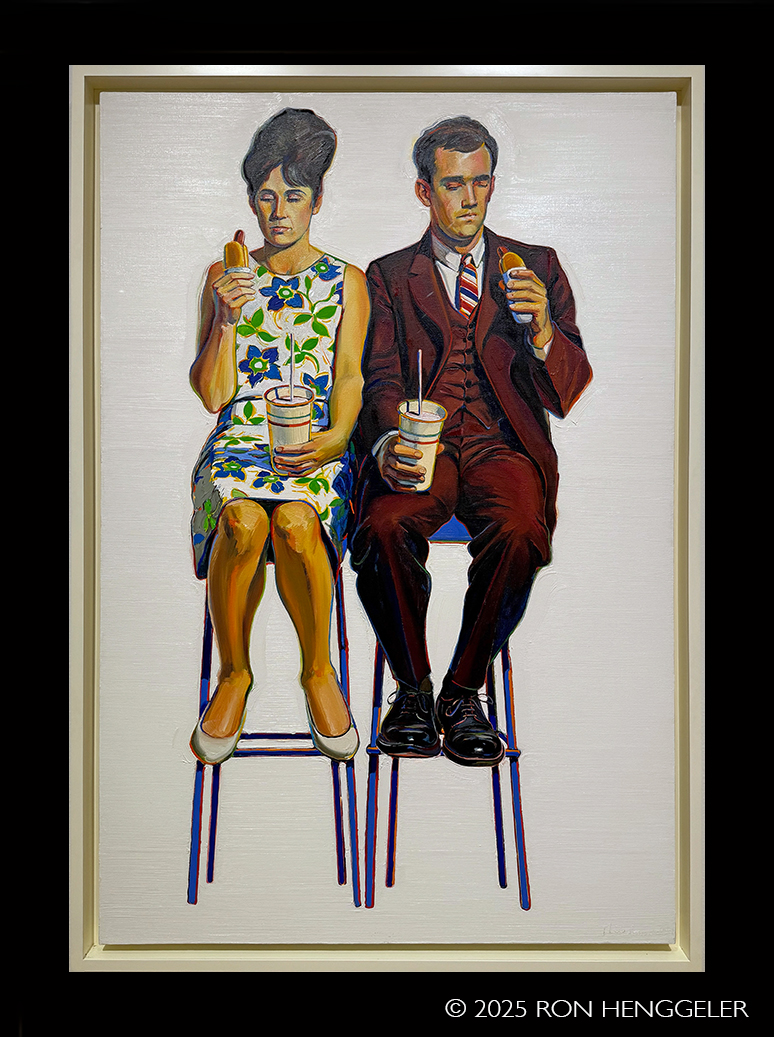

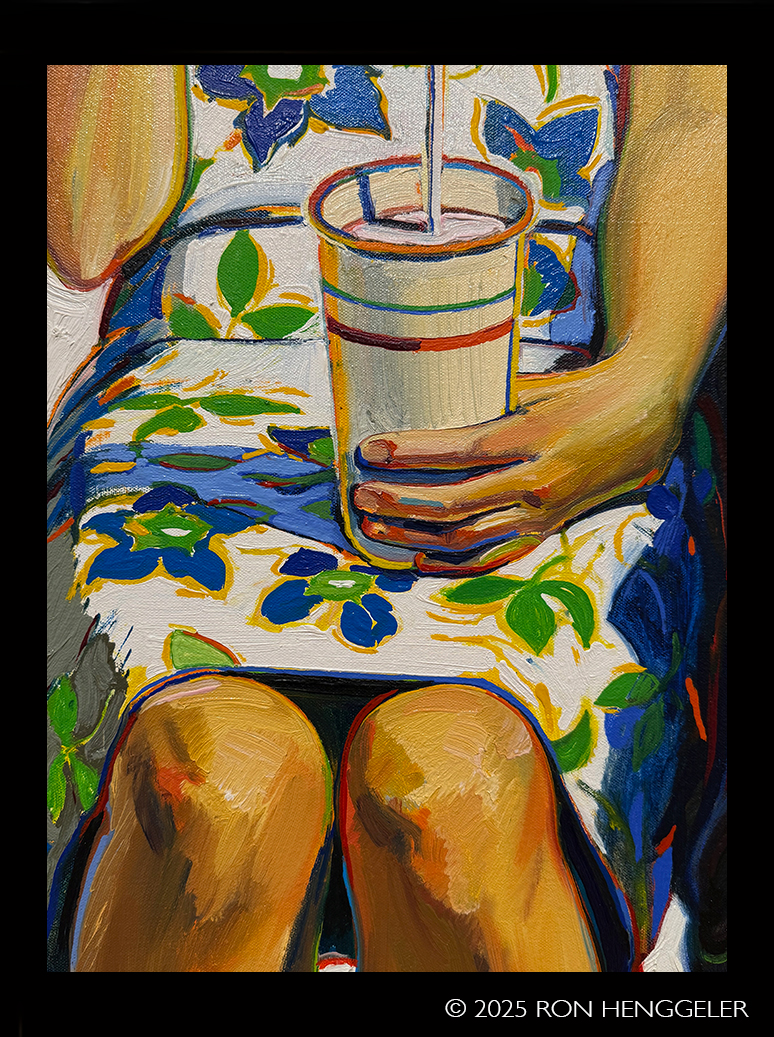

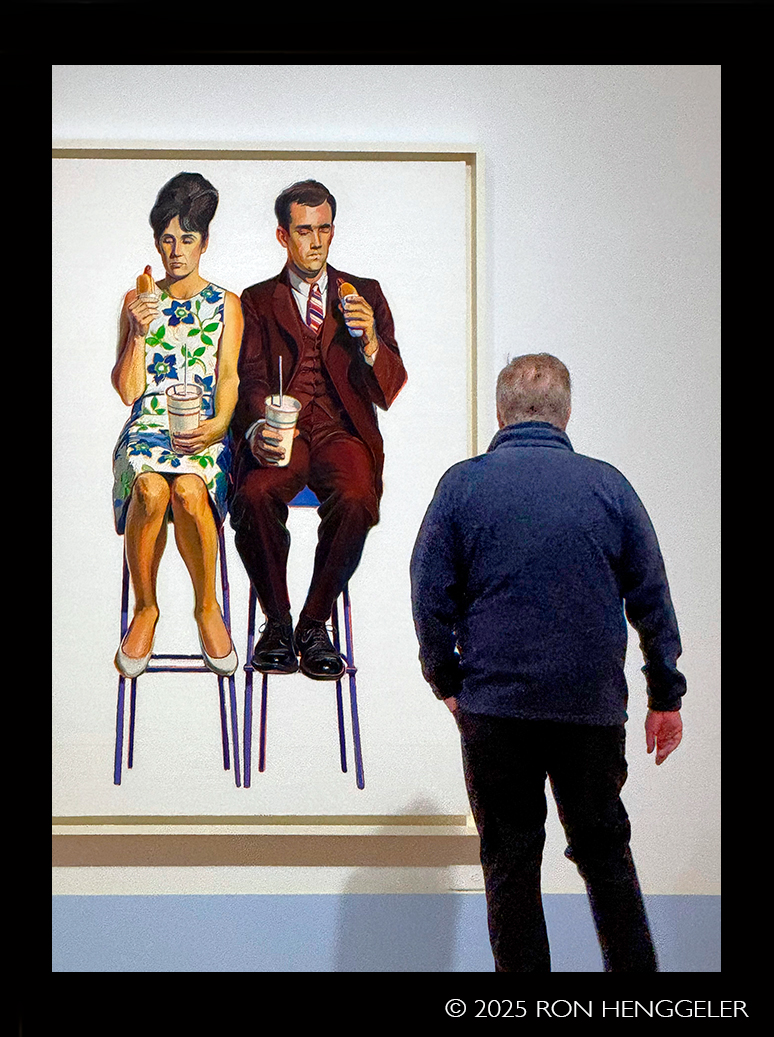

Eating Figures (Quick Snack), 1963

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's Eating Figures appears to be an example of concealed theft from Edgar Degas's L'Absinthe. At first glance, the two paintings have little in common, as Degas depicts a slouching man and woman seated in a dingy café interior. In contrast, Thiebaud's couple appears to be seated outdoors on levitating barstools set against a bright white ground that lacks any shadows or context. They simultaneously rest large frozen drinks with upright straws on their thighs while holding their hot dogs with hesitancy, if not outright distaste.Despite being painted in the radically different settings of nineteenth-century Paris and twentieth-century Sacramento, Degas's and Thiebaud's paintings share a defining mood, in which women and men are overcome by a world-weariness that cannot be remedied with alcoholic drinks or revived with fast food.

Private collection, courtesy of Acquavella Galleries, New York |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Eating Figures (Quick Snack), 1963

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Eating Figures (Quick Snack), 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Eating Figures (Quick Snack), 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Eating Figures (Quick Snack), 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

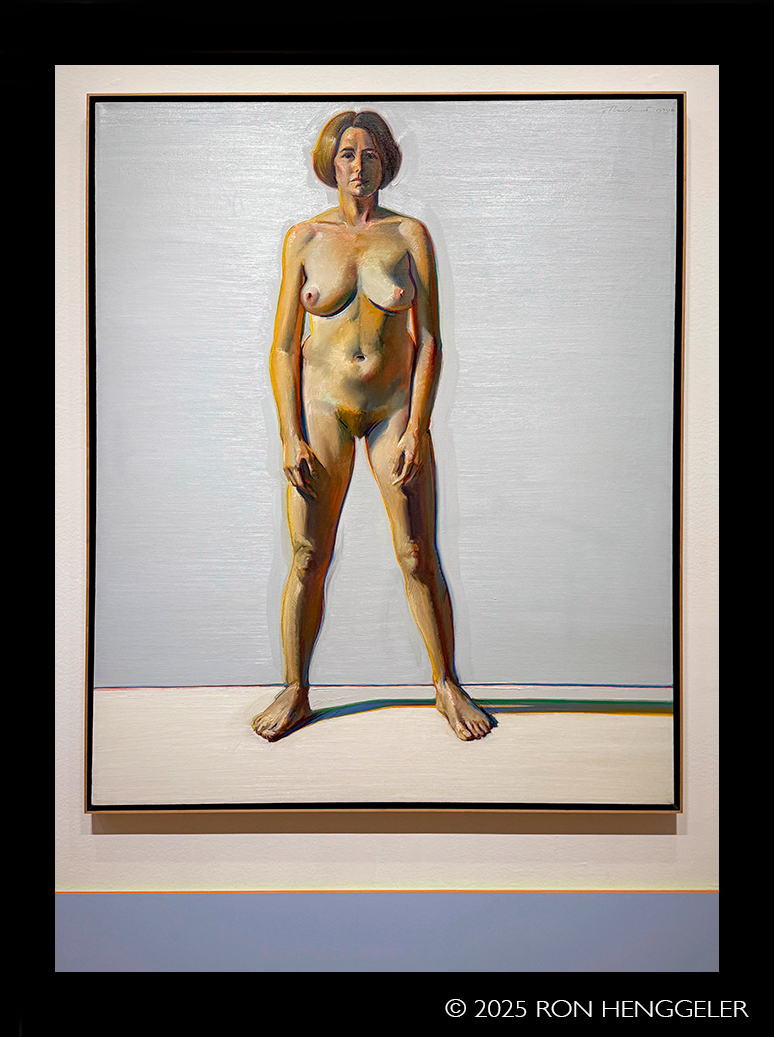

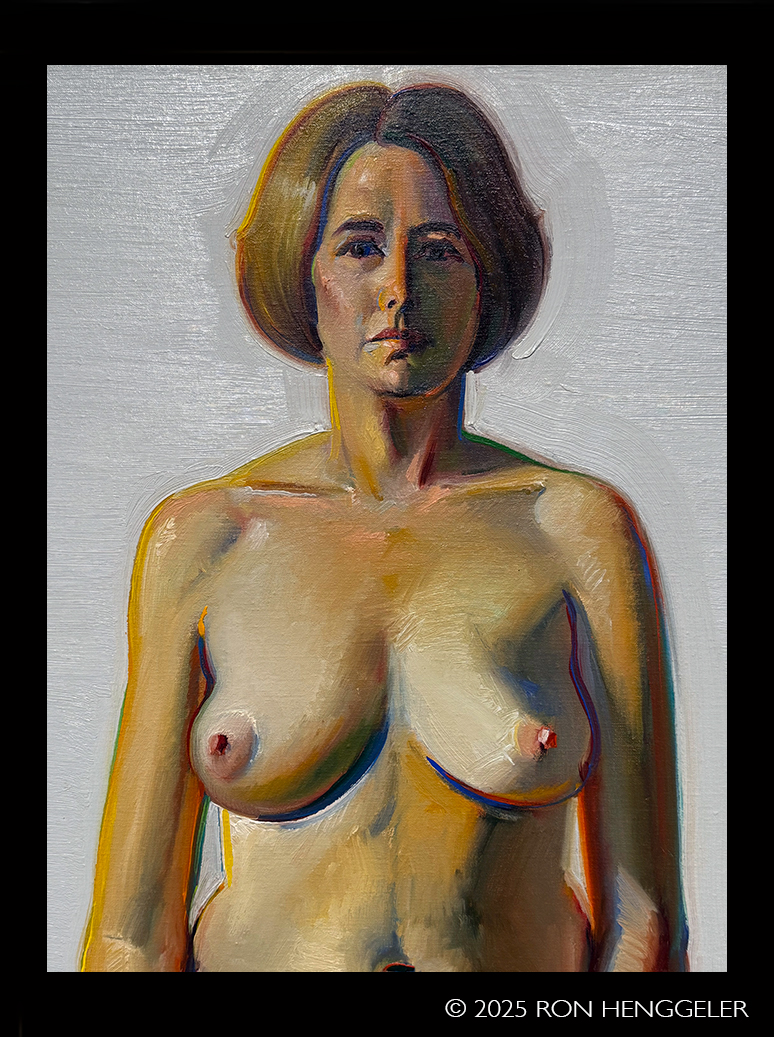

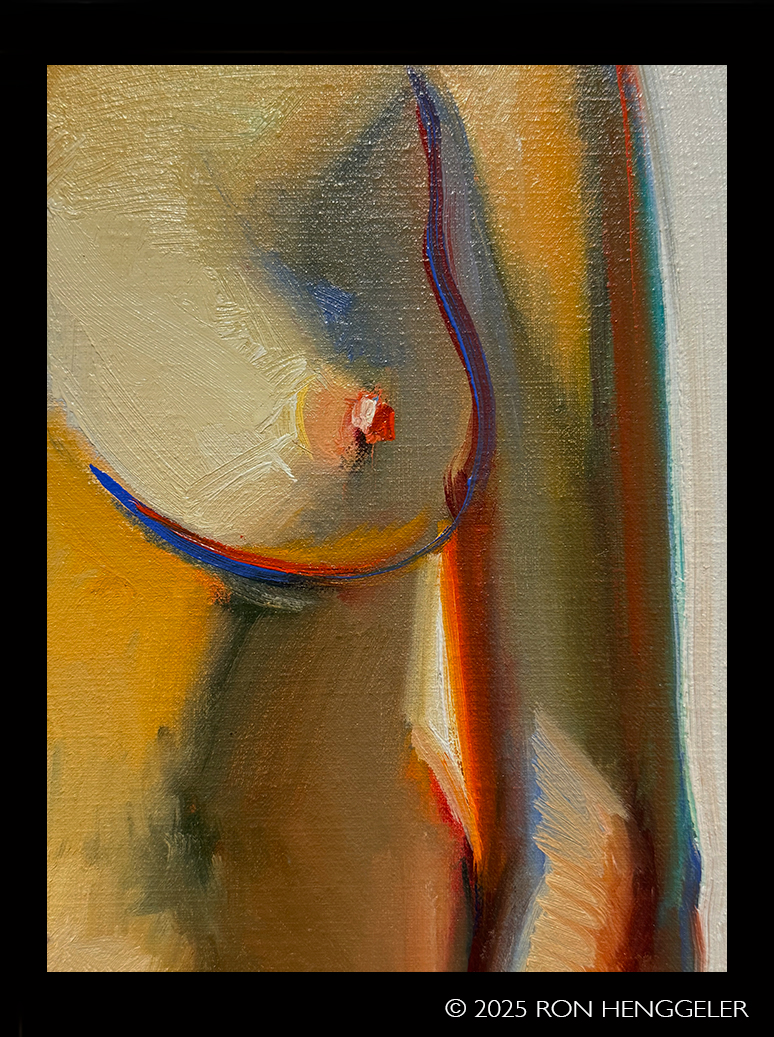

Nude, Standing, 1975-1976

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's interest in painting the human figure led him to the artworks of the American realist Thomas Eakins.The initial impact of Thiebaud's full-frontal Nude, Standing reminds American viewers of the country's history with natural nudity, which led to Eakins's forced resignation from his teaching position in 1886, after he removed the loincloth from a male model in the presence of female students.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Nude, Standing, 1975-1976

Oil on canvas

The year after completing this painting, Thiebaud observed: "The painter I have been interested in recently, of course, is Thomas Eakins. In the last four or five years he has become a great hero of mine. I find Eakins very complex and interesting to think about. As much as I like realist painting, there are certain kinds of realist painting which, for me, are inescapably complex; it is that business of giving all of the clues and none of the secrets." |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Nude, Standing, 1975-1976

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

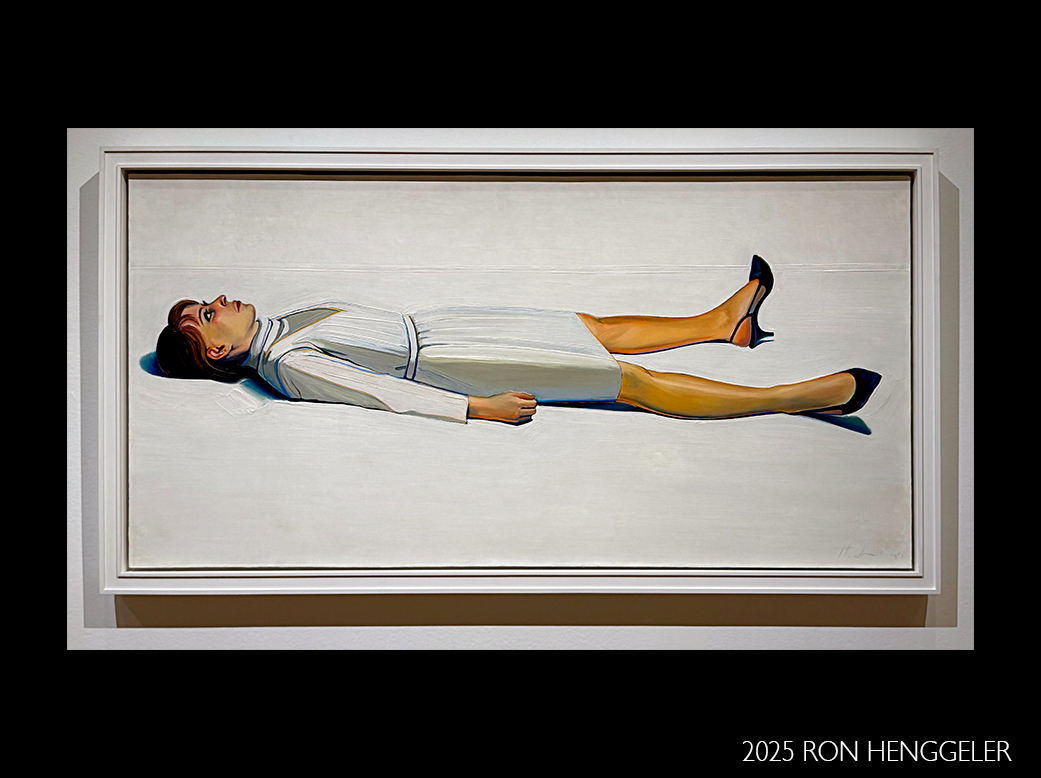

Supine Woman, 1963

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's Supine Woman, with its radical perspective and flattened human form, pays overt homage to Édouard Manet's The Dead Toreador. However, despite its resemblance to a crime scene, Thiebaud's painting of his eighteen-year-old daughter, Twinka, frustrates any specific interpretation. Unlike Manet's bullfighter, who has been killed in the midst of an inherently dangerous profession, Thiebaud's human still-life subject appears to be an ordinary teenager on the verge of adulthood, who has inexplicably fainted or fallen and stares upward with open eyes.

Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, 2009.17 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Supine Woman, 1963

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Makeup Girl, 1981-2012

Oil on canvas

In 1963, Thiebaud created the first of numerous works that reinterpret Édouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.This Parisian scene has provoked speculation regarding the mirror that creates a picture within a picture, and the position of the viewer in relation to the man reflected in the mirror.

In 1982, soon after Thiebaud commenced Makeup Girl, a critic noted Thiebaud's interest in Manet's painting as a source of inspiration:

"On an easel in his San Francisco studio is a drawing of a woman at a cosmetics counter in a highly stylized department store environment. He suggests that in contrast to his earlier portraits, 'this is different, more theatrical, more isolated-with different lighting and ten thousand shades of blue. Perhaps it will become a whole department store interior painted in high-value tonalities with lots of brilliant little infusions of color. ... Of course, l'll want to take a look again at Manet's girl in the Bar at the Folies-Bergère.''

Courtesy of Acquavella Galleries, New York |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Makeup Girl, 1981-2012

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

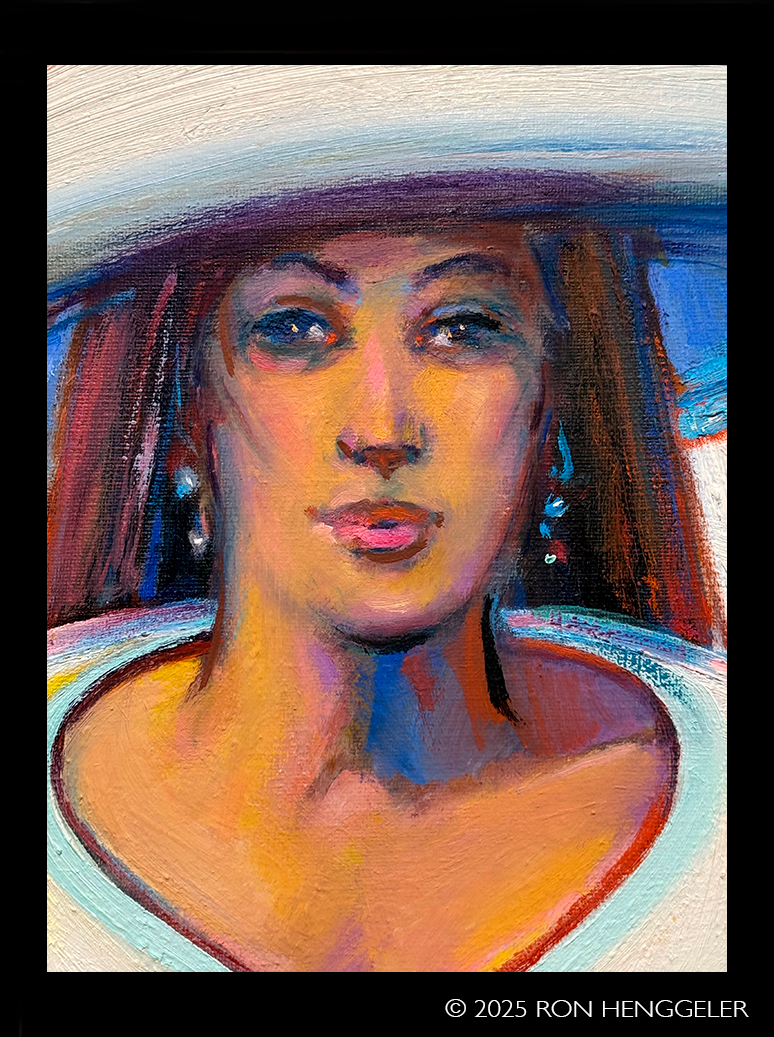

Woman in White Hat, 2014/2015

Oil on linen

Thiebaud created two major types of paintings inspired by Édouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, ones in which the viewer is offered products by a salesperson at a department-store counter, and ones like Woman in White Hat, in which the subject appears to look at them-selves in a mirror while dressing or applying makeup.

Although many historical paintings depicting beautiful women with mirrors symbolize the transitory nature of beauty, which fades with time, Thiebaud instead seems to suggest links between an artist composing and painting a canvas and a sitter composing themselves in clothes and painting themselves with makeup. The heart-shaped neckline, which mirrors Thiebaud's trademark heart signature, hints at the degree to which the artist identifies with his subject.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Woman in White Hat, 2014/2015

Oil on linen

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Woman in White Hat, 2014/2015

Oil on linen |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

"I guess one of my quarrels with modernism is the emphasis on the so-called self... . The idea is to become one with others.To surrender your private, selfish self to something bigger than you are. I think the charge and responsibility of painting really is to merge with your tradition, to respect it."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

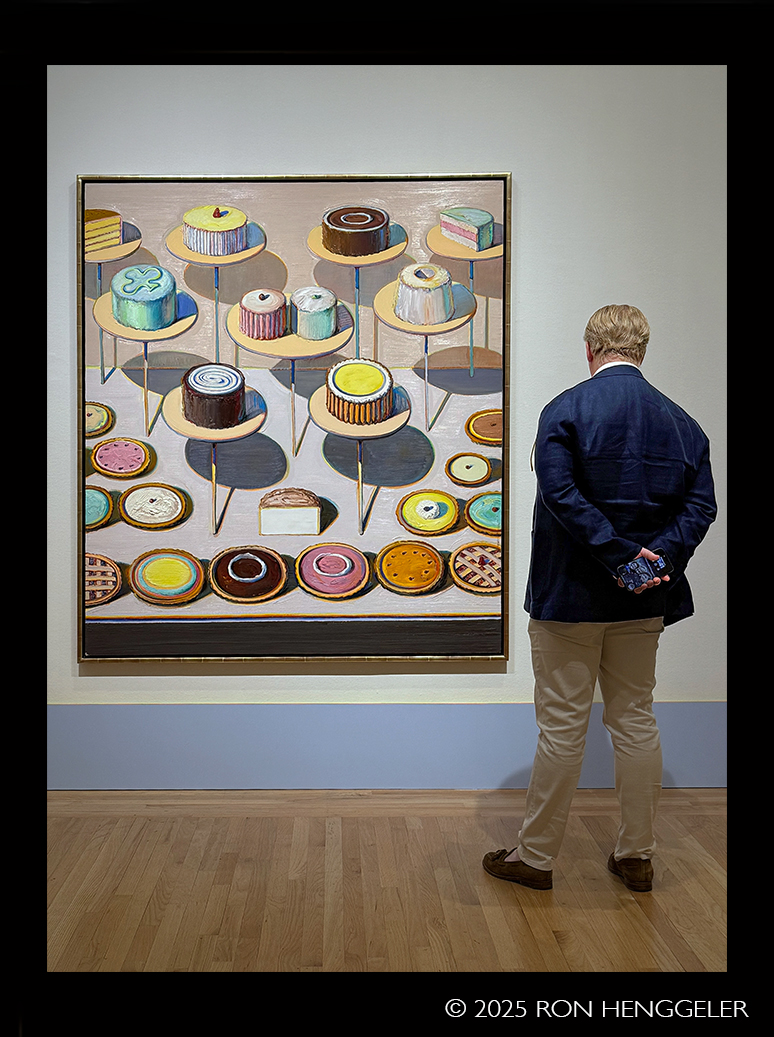

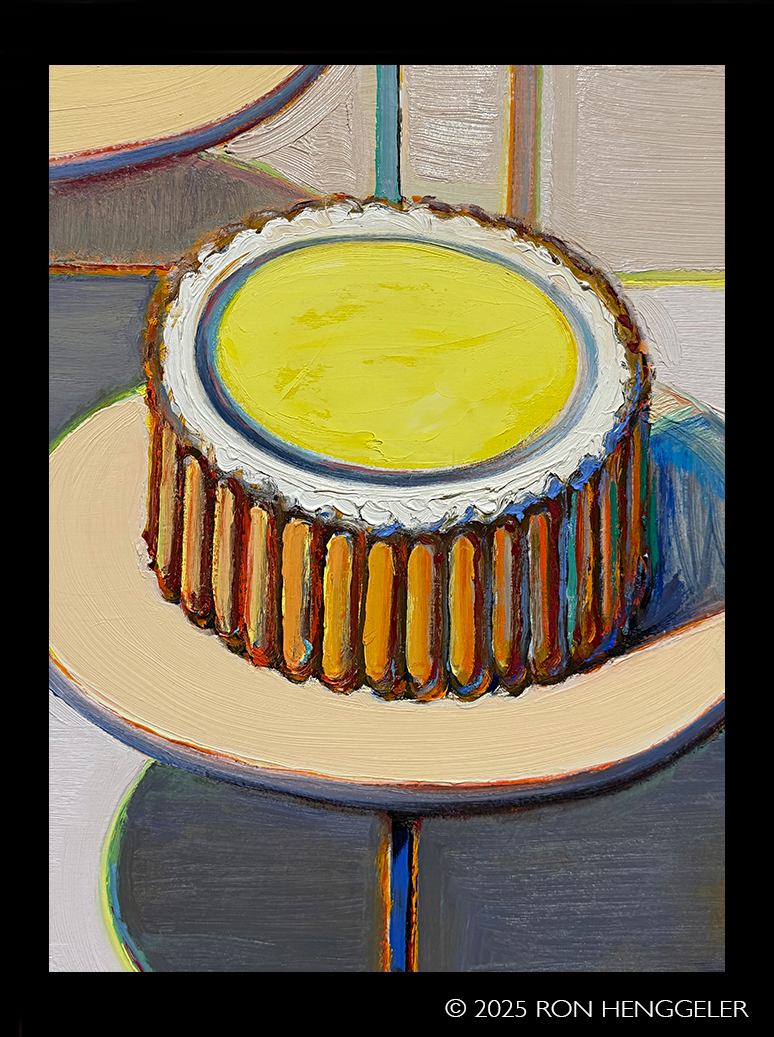

Cakes & Pies, 1994-1995

Oil on canvas

At first glance, the connections between Thiebaud's Cakes & Pies and still-life paintings by Juan Sánchez Cotán, whose artworks Thiebaud acknowledged "stealing" for his own compositions, are not obvious. However, the Spanish artists distinctive compositions, in which the various fruits and vegetables are spotlit like actors on a stage, can be seen as models for Thiebaud's own stagelike compositions.

Both Sánchez Cotn's and Thiebaud's compressed compositions depict a shallow space filled with artfully arranged foods that rest on a lower tilted-up surface and are suspended above, with some already cut for consumption. More poetically, both artists endow their works with an aura of physical and emotional suspense created by dangling produce and poultry from thin strings or by balancing top-heavy cake stands on slender poles with no bases.

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Bebe and Crosby Kemper Collection, Gift of the Enid and Crosby Kemper Foundation, 1995.1 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Cakes & Pies, 1994-1995

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Cakes & Pies, 1994-1995

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Cakes & Pies, 1994-1995

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Cakes & Pies, 1994-1995

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Cakes & Pies, 1994-1995

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

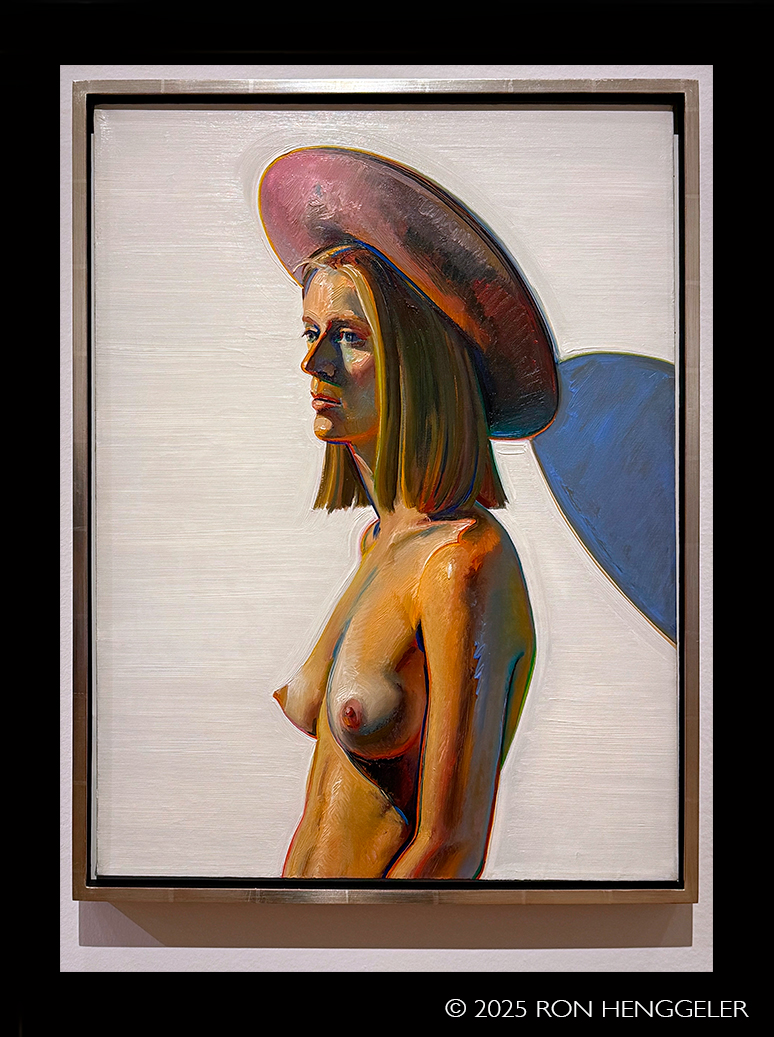

Girl with Pink Hat, 1973

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud cited the French artist Edouard Manet (along with the American Thomas Eakins and the Italian Giorgio Morandi) as one of the historical artists he would most like to be paired with in an art exhibition. Thiebaud particularly admired Manet's ability to draw upon tradition, while simultaneously helping to pioneer modern painting.

"That kind of one-to-one immediate stroke, which came from a whole tradition of painting-from [Diego] Velázquez and [Frans] Hals and Manet through [John Singer, Sargent, and the great Spanish painter, Joaquin Sorolla, all of whom have that same kind of flashy bravura, no babying up, no going over, you have got to do it as you go. It can be the most terrible kind of cheap painting on one hand or the most eloquent on the other."

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Jeannette Powell,

2010.97 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

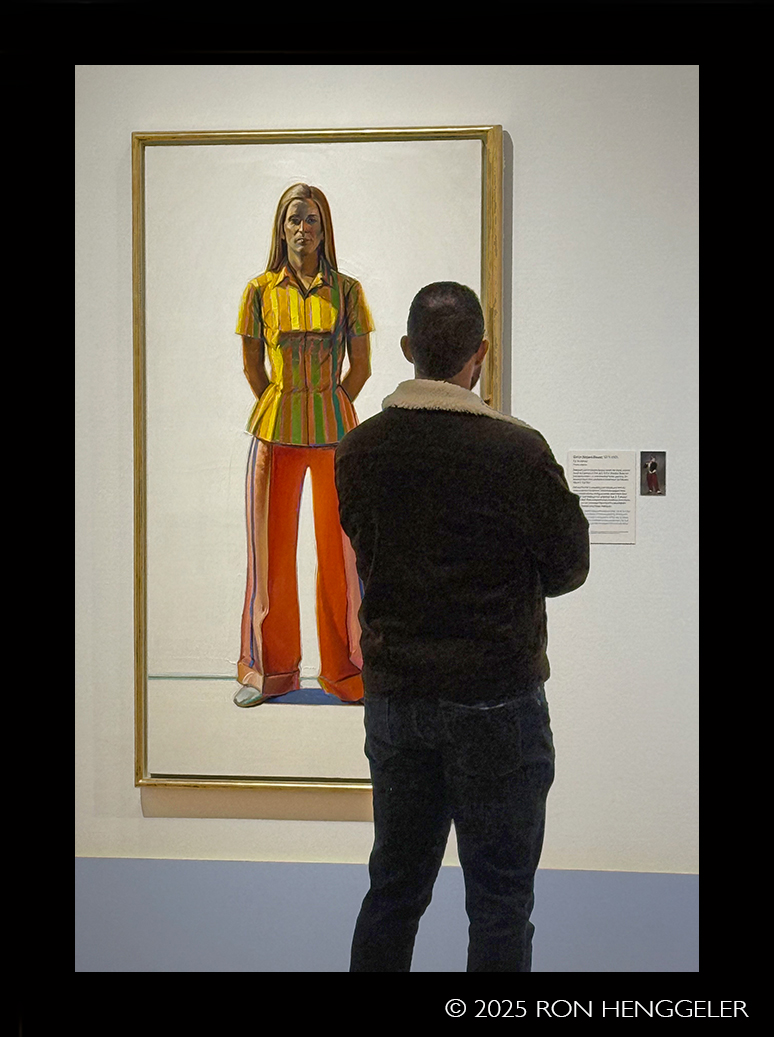

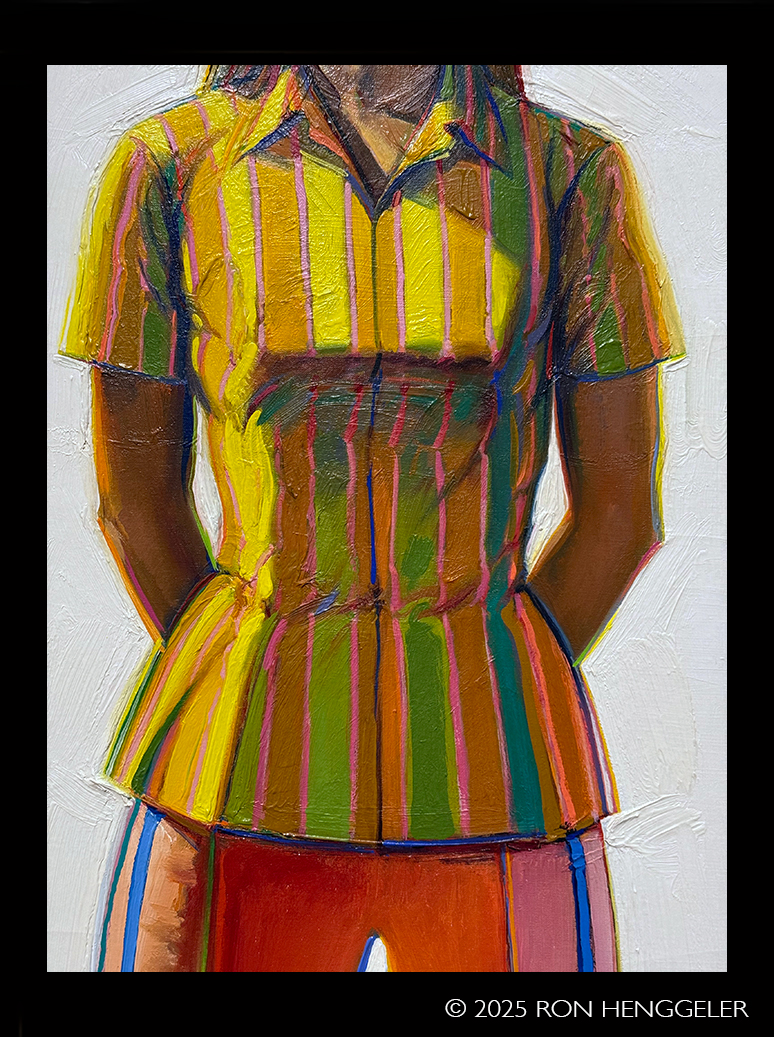

Girl in Striped Blouse, 1973-1975

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Thiebaud's Girl in Striped Blouse recalls the vividly colored

American fashions of the early 1970s. Whether these stri-ped pants existed, or were invented for the painting, the attraction lay in their similarity to those worn by Édouard Manet's The Fifer.

Without the fifer's undulating pant stripes and the tiny shadow behind his left foot, which help suggest three-dimensional volume, his figure would seem more like a flat paper doll floating in an undefined space. Thiebaud appropriated these compositional innovations from Manet, who in turn had borrowed them from the seventeenth-century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Girl in Striped Blouse, 1973-1975

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's Girl in Striped Blouse recalls the vividly colored

American fashions of the early 1970s. Whether these stri-ped pants existed, or were invented for the painting, the attraction lay in their similarity to those worn by Édouard Manet's The Fifer.Without the fifer's undulating pant stripes and the tiny shadow behind his left foot, which help suggest three-dimensional volume, his figure would seem more like a flat paper doll floating in an undefined space. Thiebaud appropriated these compositional innovations from Manet, who in turn had borrowed them from the seventeenth-century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez.

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Girl in Striped Blouse, 1973-1975

Oil on canvas

"I don't feel myself being particularly original. I love the idea of being in the tradition of bravura painting, starting with maybe Velázquez and coming down all the way to Manet through hundreds of wonderful bravura painters. So that certainly can't be counted as original. Who's to say about originality?"

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

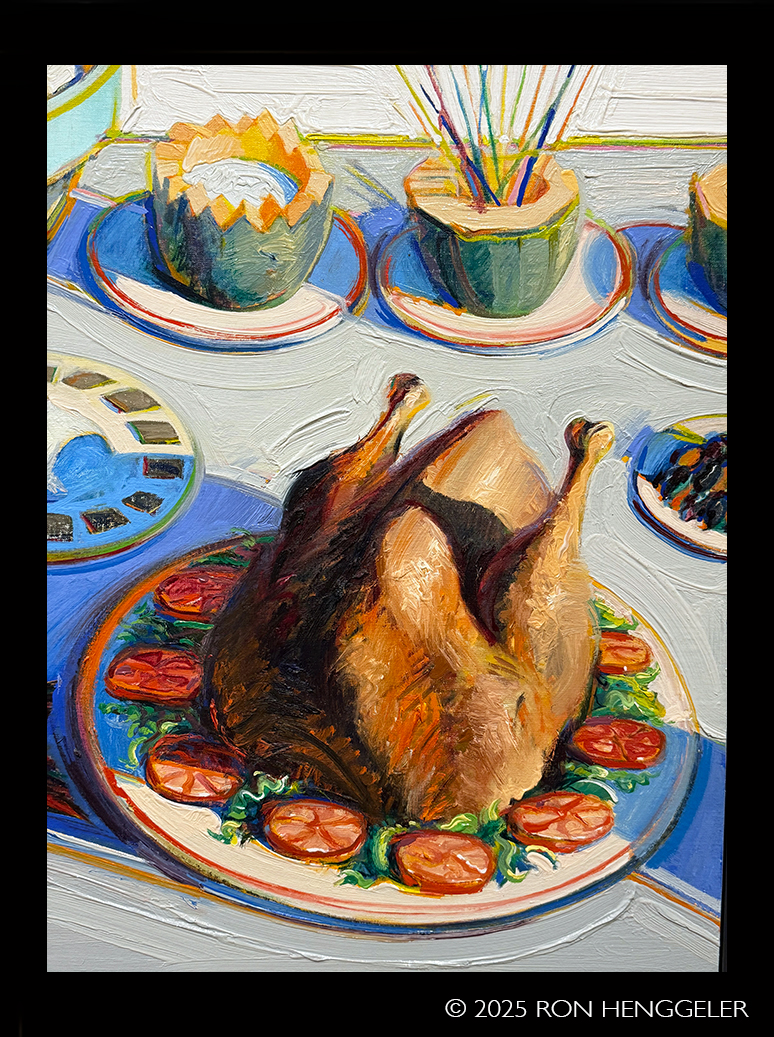

Buffet, 1972-1975

Oil on canvas

Although Thiebaud most admired the simpler tabletop still-life paintings of the twentieth-century Italian Giorgio Morandi, he also was drawn to more elaborate seventeenth-century European examples. These feasts for the senses served as prototypes for his own images of American abundance-and excess. Buffet reprises the bird's-eye perspective and also the ham, fish, and poultry subjects of Flemish artist Jacob van Hulsdonck's feast.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Jon and Shanna Brooks,

2019.399 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Buffet, 1972-1975

Oil on canvas

"The potential of still-life painting is infinite, and all you have to do is look at what people are doing in still life, but remembering that when you go to the Metropolitan Museum and see a Dutch painting this big, including ten or fifteen objects-that's your challenge. You've got to come up with something that is the measure of that, so you can spend a lifetime."

Wayne Thiebaud

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Buffet, 1972-1975

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

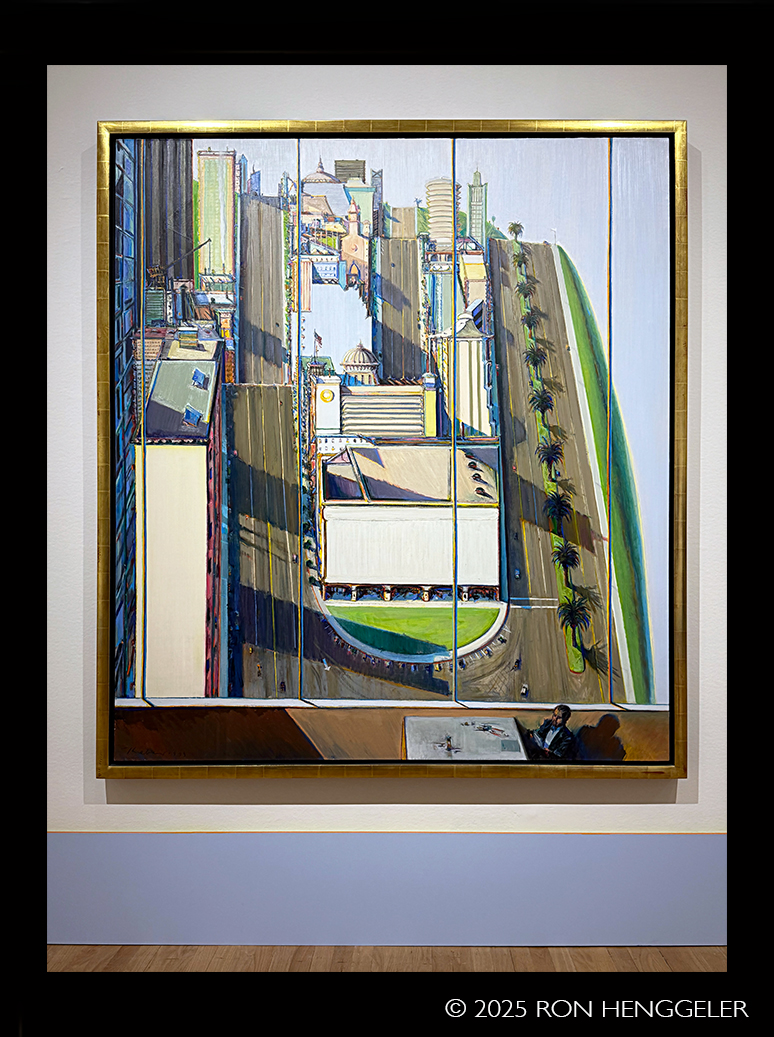

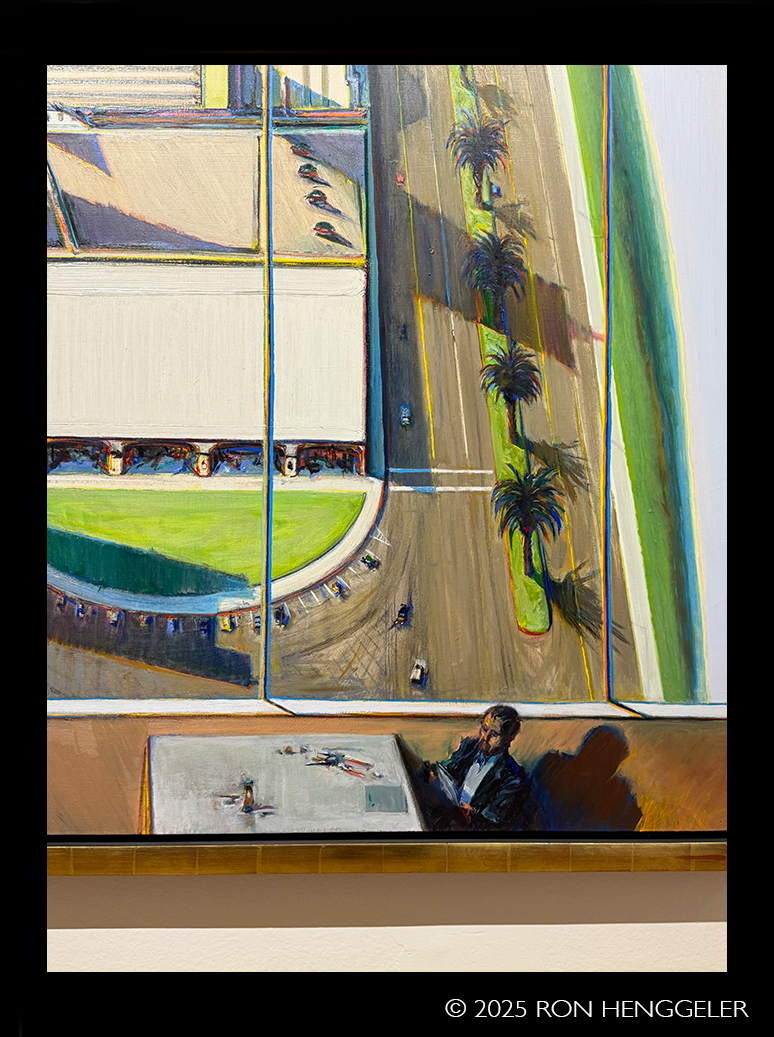

Window Views, 1989-1993

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud observed that Window Views was inspired by Pierre Bonnard's Dining Room Overlooking the Garden, which also fuses a flat window, subdivided vertically, with a foreground table and a solitary human figure.

Elmer Bischoff's Interior with Cityscape also appears to have drawn inspiration from the Bonnard painting, thus underscoring its appeal for rendering San Francisco-inspired cityscapes.

While Bonnard seamlessly fuses his interior, exterior, and figure, Bischoff creates a physical and emotional gulf between his female and male subjects. Thiebaud similarly introduces a note of unease by depicting his solitary diner overwhelmed by the sheer size of the metropolis beyond the plate-glass windows.

Private collection |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Window Views, 1989-1993

Oil on canvas

"I'm still trying to figure out whether those [cityscapes] work or not, but that was the idea-to have different projective systems in terms of interior and exterior. It's also a little bit based on influence from Bonnard, who does that interesting interior/ exterior relationship between the garden and the breakfast table."

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

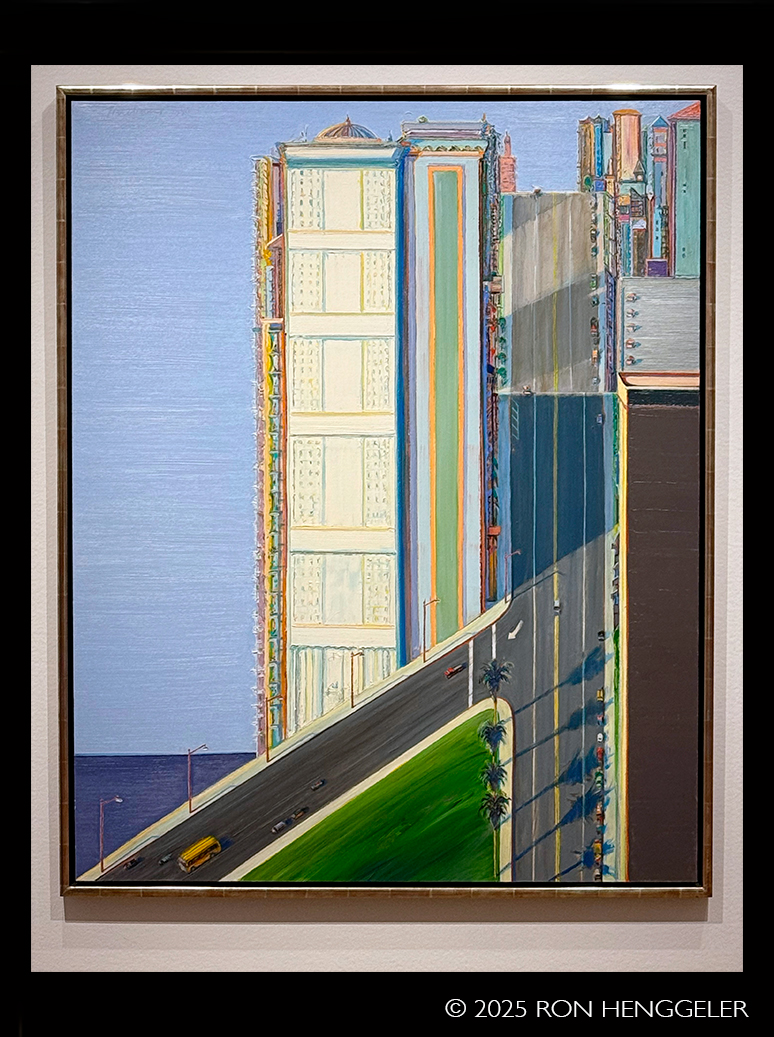

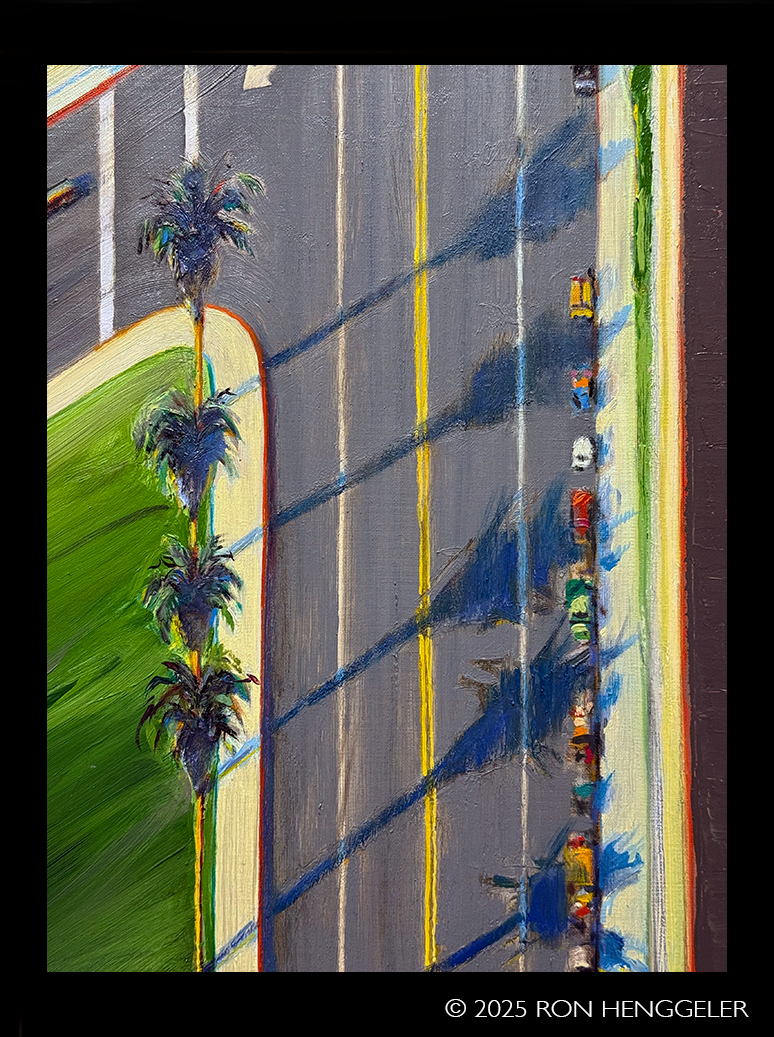

Day Streets, 1996

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's Day Streets, while not necessarily a specific visual match for Richard Diebenkorn's Ocean Park #30, similarly emphasizes the two-dimensional picture plane through structural lines, while suggesting space with large color planes. Transferring Diebenkorn's interest in compression and spatial ambiguity onto a supposedly representational cityscape, Thiebaud creates both physical disorientation and psychological unease, underscoring the human drive to replace nature with unstable, manmade structures.

While Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series employed abstraction that evoked representation, Thiebaud's city paintings utilized representation that verged on abstraction. This comparison exemplifies his belief that whether an artist works primarily with representation or abstraction, the pictorial concerns are similar, and that representation is always an equally viable option.

Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Gift of the William T. Kemper Charitable Trust, UMB Bank, n.a., Trustee, and the R. C. Kemper Charitable Trust, 1996.69 |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Day Streets, 1996

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Day Streets, 1996

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

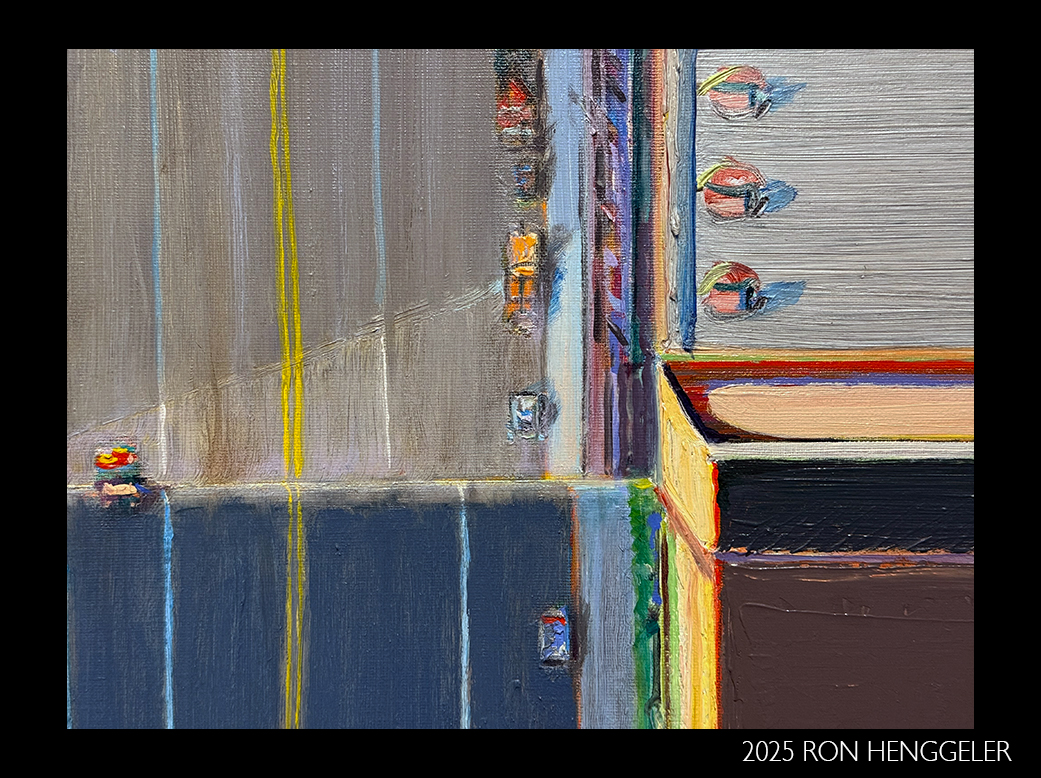

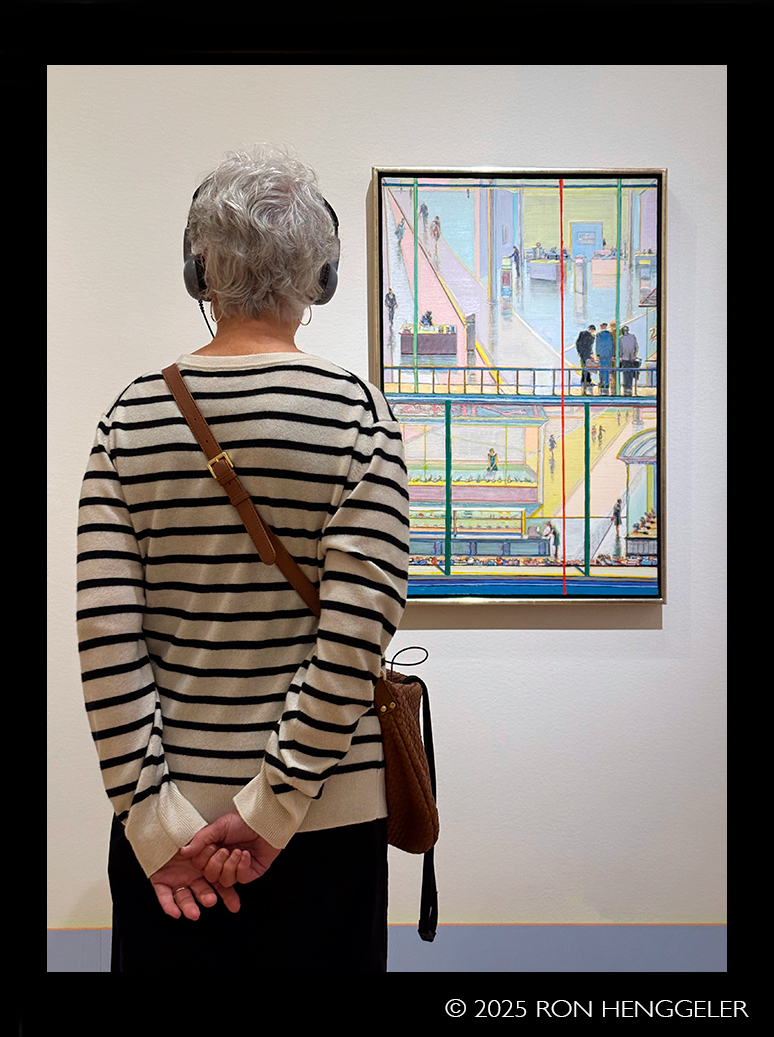

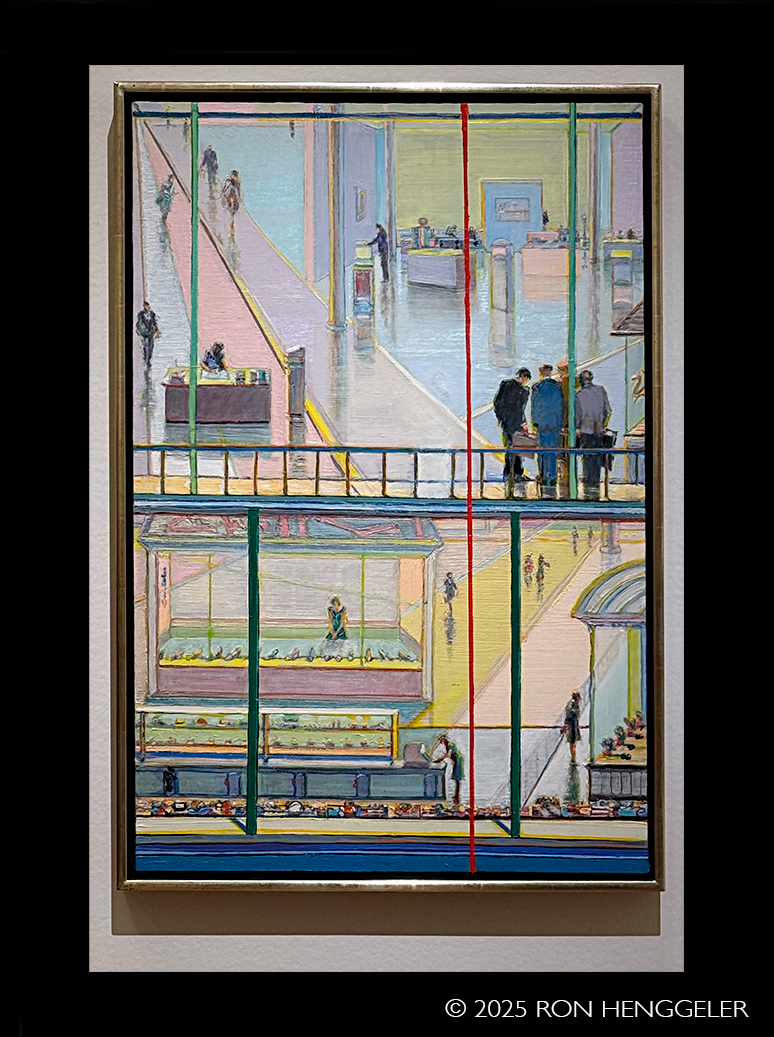

Office and Shopping Mall, 2005/2021

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud admired Piet Mondrian for his ability to paint both representational flower studies and geometric abstractions. Office and Shopping Mall reimagines the Dutch artist's iconic grids as the architectural support beams of a building, while simultaneously incorporating both flattened and deeply recessive space.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

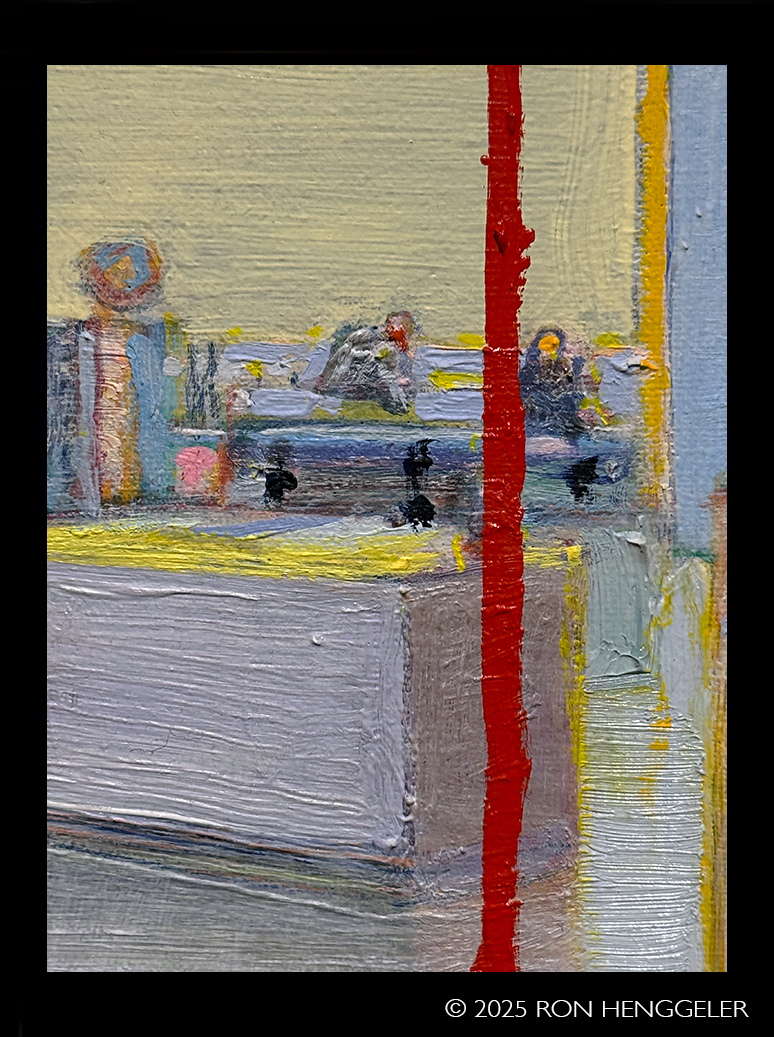

Detail of: Office and Shopping Mall, 2005/2021

Oil on canvas

"When Piet Mondrian was talking to a friend in the New York studio, he walked to his window, pulled down the blind, and said, I can't stand all that disorganization out there.' To make a life of order out of the buzzing confusions of this wondrous but difficult world demands our best efforts. As far as I can see, thoughtful paintings that try to do this have always been extremely rare. Negotiating the perceptual world into a conceptual entity of some interest and dimension is a challenge of the championship level."

Wayne Thiebaud

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Detail of: Office and Shopping Mall, 2005/2021

Oil on canvas |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Clown Boots, 2018-2019

Oil on canvas

Modeled on Belgian Surrealist artist René Magritte's disturbing image of shoes that are half actual feet, and painted with a forced smile and an eye-rolling grimace, Thiebaud's Clown Boots acknowledge the absurdity of life and the difficulty of consistently maintaining a cheerful public facade.

Collection of the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

DEtail of: Clown Boots, 2018-2019

Oil on canvas

"The reason I don't like classical Surrealism, if there is such a thing, is that it seems already to have arrived before you've even seen it. Even a good painter like Magritte-his ideas put me off. The ideas may as well be a Saturday Evening Post cover, except that Magritte and [Giorgio] de Chirico are good in the way that [Giorgio] Morandi is good, in knowing just how to give you enough in the substance of paint."

Wayne Thiebaud

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

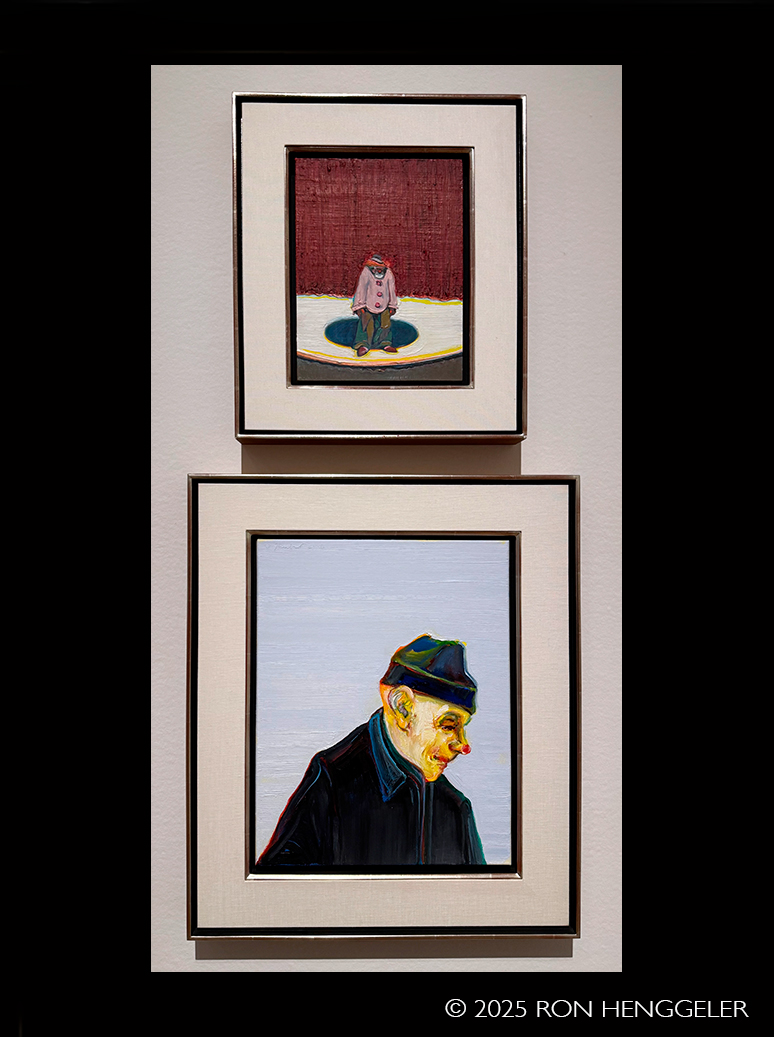

(Top) Clown with Red Hair, 2015

Oil on canvas

(Bottom) One-Hundred-Year-Old Clown, 2020

Oil on canvas

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Clown with Red Hair, 2015

Oil on canvas

Painted by the artist at the age of ninety-five, the clown in Thiebaud's surrogate self-portrait, Clown with Red Hair, stands in the spotlight upon a stage before a closed curtain but does not perform or bow, leaving the clown without a purpose and the viewer without a clear narrative.

The source for this subject most likely is Edward Hopper's Two Comedians, a self-portrait of the artist with his wife, taking a final bow one year before his death.

"The architecture, the restaurant, the empty theatre with one person sitting in it, it's very poetic. If he'd [Hopper] really slicked those up, maybe they wouldn't have been so interesting. That's the query about painting.... You can talk a great deal about it, and then when you come down to it, as with Hopper: 'just what is it about his char-acterization, what he leaves out and what he puts in, that makes the difference?'"

Wayne Thiebaud |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

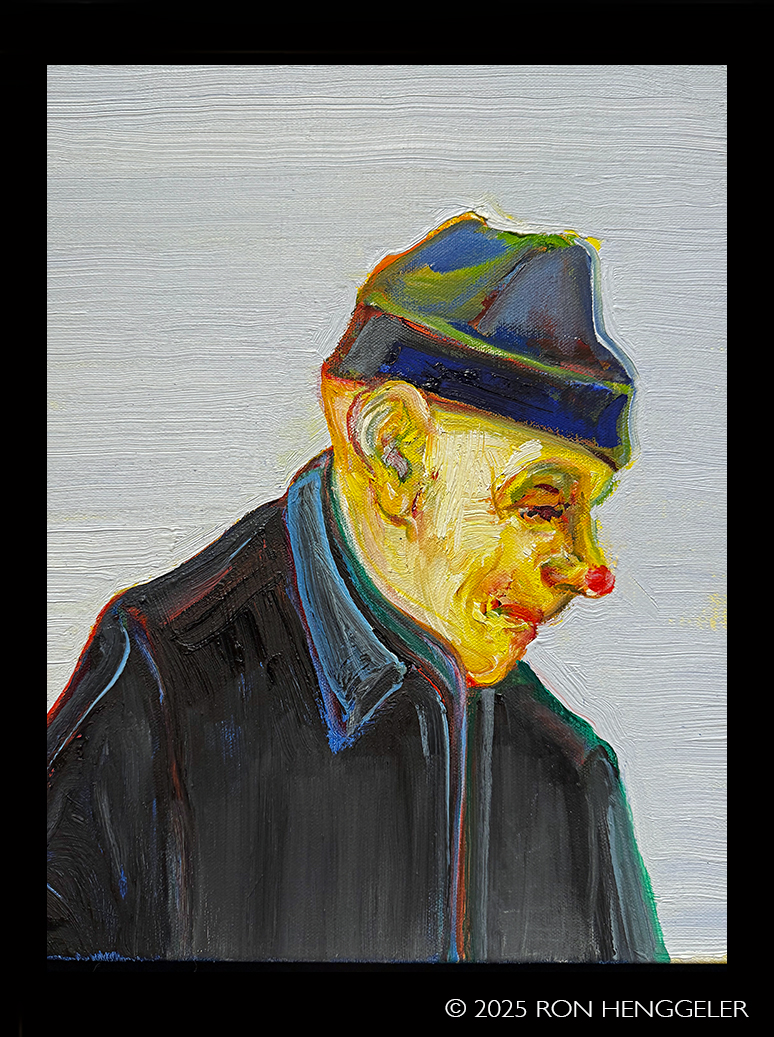

Detail of: One-Hundred-Year-Old Clown, 2020

Oil on canvas

Thiebaud's moving self-portrait One-Hundred-Year-Old Clown bravely records the physical and emotional impact of a century of life and decades of work. The clown subject, traditionally combining comedy and tragedy, took on even greater meaning following the loss of his son, Paul, in 2010, and his wife, Betty Jean, in 2015.

The painting nonetheless reveals Thiebaud's enduring sense of humor, as he transformed his hat into one of his mountain paintings, while vertical lines on the jacket recall asphalt streets divided by traffic lines in his city paintings. Thiebaud's clownlike red nose appears to reference, Pierre Bonnard's The Boxer. However, unlike the French artist's self-portrait, in which the artist appears to challenge the viewer to fight, Thiebaud turns away, as if to exit from his painting-and perhaps from life itself.

Collection of Matt and Maria Bult

A short video that coinsides with the Wayne Thiebaud exhibit at the Legion of Honor. Click here: Art Thief: Lessons from Wayne Thiebaud

Credits: The texts with the photos in this newsletter were taken from the placards on the walls next to each painting at the museum exhibit. |

|

| |

|

|